A little more than seven years ago, I wrote “travel stunt” essay — “Around the World in 80 Hours (of Travel TV)” — that recounted the experience of holing up in a Las Vegas hotel room for one week and spending all of my waking hours watching the Travel Channel. The experience was uniformly awful, save the hours I spent watching Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations — a show that was at once more entertaining, honest, and true to the travel experience than the rest of the channel’s programming combined.

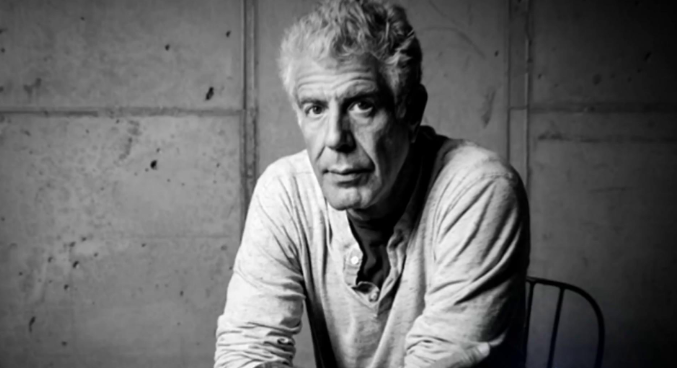

The collective outpouring of sorrow over Bourdain’s recent death has left me reflecting on his singular genius for evoking the travel experience on the small screen — something I tried to articulate all those years ago in the excerpt that follows.

I’ve noticed that there’s a sameness to the narrative language on all the Travel Channel shows. Since I began my TV marathon, both Andrew Zimmern and Samantha Brown have used the exact same phrases — “vacation paradise,” “land of contrasts,” “it doesn’t get any better than this” — to describe wildly different places and experiences. The words “heaven,” “breathtaking,” “dreams,” “treasure,” and “unforgettable” are intoned like Travel Channel mantras, and just today I heard the phrases “hidden gem,” “secret gem,” and “unique gem” on three successive programs.

This type of language belongs to a distinctive media-dialect called “travelese,” a word journalist William Zinsser coined in his 1976 book On Writing Well. “Nowhere else in nonfiction do writers use such syrupy words and groaning platitudes,” Zinsser noted. “It is a style of soft words which under hard examination mean nothing.” At the time Zinsser was alluding to print-based travel journalism, and 35 years later the overwrought cadences of travelese continue to plague magazine, newspaper, and guidebook writing.

The thing is, for all the consumer travel articles sopping with words like “quaint” and “wondrous,” the print world offers plenty of verbally disciplined, literary-minded travel reportage by writers like Peter Hessler, Tim Cahill, Susan Orlean, Pico Iyer, Kira Salak, Gary Shteyngart, and Paul Theroux. Unfortunately, travel television does not appear to offer a comparable respite from its more mindless tropes: Almost without exception its program language is indecipherable from that of its commercials.

The network’s sole exception to this phenomenon is Anthony Bourdain, whose No Reservations is at once counterintuitive, given to opinionated perspective, and self- aware of its limitations as a TV show. Yesterday Bourdain guided us off the sun- dappled tourist-trail to visit the eateries of “the three most fucked-up cities in America” — Baltimore, Detroit, and Buffalo. By the end of show he had done a fair amount of rust-belt dining, but he’d also given the audience subtle lessons in socio-economics, immigration history, and urban planning. In Buffalo, he refused to discuss hot-wings (“you can have Al fucking Roker describe them to you on some other show,” he said). Today’s Miami-based episode simultaneously skewers South Florida tourist clichés, documentary TV fakery, and the basic assumptions of every other food-travel show on television. A running joke of the episode is Bourdain’s stubborn avoidance of Miami’s most stereotypical cuisine-culture; he eventually relents during the final moments of the show. “I’ve finally done the Cuban thing,” he quips in the concluding scene, “satisfying my network masters’ request.”

…If there were an ideal indicator of what the Travel Channel might one day become, it would be Anthony Bourdain’s refusal to devolve into a telegenic caricature. The No Reservations host is consistently hip and insightful and funny — but what makes his show stand out is that he’s not afraid to express his real opinion about things. It’s astonishing how seldom this happens on travel shows. The Travel Channel sheepishly alludes to this in its Bourdain promo teasers, suggesting that there’s an upbeat, camera-friendly “Good Tony,” who likes what he eats and sees, and a snarky, irritable “Bad Tony,” who drinks too much, despises culinary clichés, and ridicules his producers. In other words, Bourdain has the temerity to express a point of view that goes beyond the tidy, self-contained dictates of television.

In a Texas-Mexico border episode, for example, Bourdain refuses to buy into stereotypes — pointing out how American perceptions of Mexican border towns are “more a reflection of our own darker, wilder sides than a true reflection of Mexico.” His take on Mexican drug culture is equally pointed: “With all the attention Mexico’s drug cartels have gotten satisfying America’s bottomless hunger for illegal drugs,” he says, “you might be surprised to find there’s nearly as much business catering to grandma’s bladder-control problem or grandpa’s erectile dysfunction.” As he travels the border region, eating street-food tacos in Mexico and chicken-fried steak in Texas, Bourdain variously pokes fun at his cameraman, debunks the notion that nachos are authentically Mexican, alludes to George Orwell, buys a stash of Demerol, and meets a Veracruz-born chef who prepares the finest Japanese cuisine in Laredo.

In hosting a show so stubbornly wedded to his unique sensibilities, Bourdain hints at a universally relevant notion: that travel — if one can view it as more than a consumer act — has a way of revealing a world more complicated and exasperating and unexpectedly delightful than one could ever imagine sitting at home.