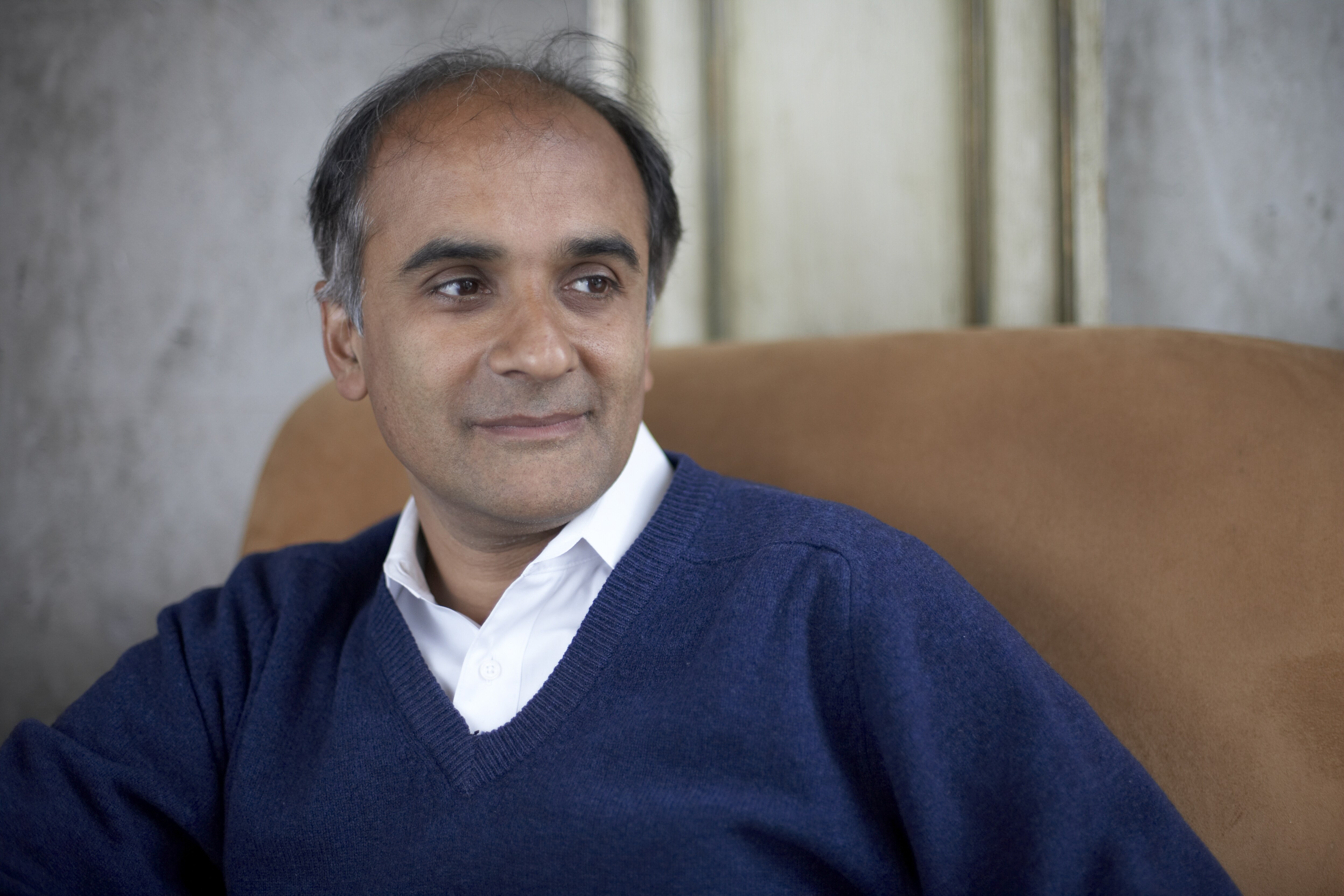

Pico Iyer is one of the most revered and respected travel writers alive today. He was born in England, raised in California, and educated at Eton, Oxford, and Harvard. His essays, reviews, and other writings have appeared in Time, Conde Nast Traveler, Harper’s, the New Yorker, Sports Illustrated, and Salon.com. His books include Video Night in Kathmandu, The Lady and the Monk, Cuba and the Night, Falling off the Map, Tropical Classical, and The Global Soul. They have been translated into several languages and published in Europe, Asia, South America, and North America. His latest work, due for release this month, is Abandon.

How did you get started traveling?

I think I was lucky enough to be a traveler from birth, as a child of Indian parents born in England (and an England where I never saw an Indian face), and then moving to California when I was seven and beginning to go to school, three times a year, by plane. And once the movement was in my blood, I could never get it out!

So as soon as I finished high-school I worked in a Mexican restaurant in Southern California, and saved up enough money to spend three months traveling by bus from Santa Barbara down to La Paz, Bolivia, and then flying up the western coast of South America, through Brazil and Suriname and the West Indies, up to Miami, where I took the Greyhound home. (After which, college itself was nothing but a sorry anticlimax).

And as soon as I went to graduate-school, I signed up to spend my summer vacations writing for the Let’s Go series of guidebooks, covering 80 towns in 90 days while sleeping in gutters and eating a hot dog once a week. And as soon as I joined Time magazine two years later, I took three separate vacations in Asia in the space of a year.

At every point, travel taught me that everything else paled by comparison.

How did you get started writing?

I think being an outsider, as I always was, proved to be a perfect background, and launching pad, for writing (and for traveling). Wherever I was, I was on the outside, taking notes, as it were — even when I was just walking down the street where I was born to the candy store. And I quickly found, too, that traveling quickened my longing to write; usually I never keep a diary, but as soon as I’m on the road, I find that all that I want to do is scribble and scribble and scribble in a somewhat quixotic attempt to catch all the experiences and impressions and feelings that are flooding through me. At some point I thought, “If I’m doing all this writing for myself, I might as well inflict it on some friends.”

On a more practical level, the only subject I could manage at school was mathematics — and as soon as it involved physics, I could no longer manage even that (I’m one of those people who can hardly turn on a computer without setting off a fire). The only other abstract and impractical subject I could find to study was English, and English is a perfect qualification for nothing but unemployment. Very soon I realized that I had spent eight years of my life learning to do nothing but read, and, occasionally, to write about what I was reading. So I had no option but to try to make a living out of that.

What do you consider your first “break” as a travel writer?

Without question, working for Let’s Go. At the time it seemed like real hardship — we were given $2000 with which to buy airfare to Europe and back again, and with which to travel intensively across a few countries in Europe (France, Greece, Italy and Britain, in my case) for three months. As mentioned above, this meant that one really had to live as sparingly and carefully as the $5-a-day travelers one was writing for; it also meant one had to pick places up very quickly. Every day I would take the train into a new town in the Dordogne, or the bus into a village in the Peloponnese, try to take the measure of all its hotels, restaurants and sights — not to mention its character — and then retire to my gutter to write it all up. The next day I would do the same in the next town, over and over for 90 days.

It was a strenuous way to spend one’s summers — the very opposite of a vacation — but later, when I thought I might like to write about my travels, and go to places to try to make sense of them, it proved, of course, to be the ideal training.

As a traveler and fact/story-gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

First, to get things down accurately, the first time round, since one seldom has the luxury of being able to return to a place to double-check the names and details and colors.

And second, to try to catch the feelings — the sound, the smell, the tang, of a place — immediately, before it goes. A place is like a dream, and unless you record it instantly, however tired you feel at the time, it will fade and fade, and you will never be able to recapture it.

What is your biggest challenge in the writing process?

My own personal Waterloo is always the leaving out of things (which I find impossible). Having taken seventy pages of notes on my two-week vacation, annotating every shop and street and sky I’ve seen, I often feel compelled, after I’ve returned home, to include them all. Having gone to all the trouble of recording this piquant or unforgettable moment or detail, I tell myself, how can I possibly leave it out?

Any prospective reader, no doubt, is saying, “Please leave it out.” For me the real challenge of writing about anything — especially something that’s moved you — is clarity. Most people, when traveling, have remarkable and life-changing experiences; and most of us record them in some way, in our diaries or our letters, with our cameras. But the particular challenge for a travel-writer is reproducing the excitements and movements of a trip in a way that isn’t boring or remote for the reader; his constant fear is that he will be the neighbor “sharing” with friends his ten-hour slide show of seeing pots in the Dordogne.

So the most important thing for me is clarity — in the outline, and in the telling. And the hardest thing at that stage becomes leaving immortal and indelible details and perceptions out.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint?

Travel for me is principally a joy and an adventure — a trip into the unknown — and I tend not to think of anything from the business standpoint. One of the glories of traveling is that even the poorest of us can live like a king, often, and partake of luxuries and conditions (for better and for worse) that we could never dream of at home. And so when, for example, I left Time magazine’s offices in New York after four years of writing there, I knew that I would live much better, on almost no salary at all, in a Kyoto temple than I could at the center of the ostensible glamour of Rockefeller Center.

I seldom think about the business standpoint of travel; travel for me liberates partly because it takes one away from having to think of taxes and bank balances and the stock exchange. Writing for magazines, the only challenge I have is that most travel-related magazines are picture-driven, and so if I want to write about Manila, say, or Addis Ababa — not obviously beautiful places — I have to think of ways to make them visually exciting and even alluring for a photographer.

Do you do other, non-travel-related work to make ends meet?

Nearly all my work is non-travel-related; indeed, at this point I would say that travel belongs to the non-working part of my life. I write five magazine articles a month, and because my training was in literature, most of them are about books and culture. I have also been lucky enough to have an arrangement with Time for many years whereby I write occasional essays for them in exchange for not a huge amount of money, but enough to keep me off the streets. And since I spend much of my life in a Catholic temple in California, a nondescript suburb in rural Japan and in between, in Tibet and Yemen and Easter Island, I try to bring the perspectives of those places (obliquely) into a New York-based magazine that might otherwise draw its wisdom from Wall Street and Washington.

What travel authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

Though I left Britain as soon as I could — at the end of my undergraduate education — I must confess that I still turn to the British for classic travel-writing, often: to Jan Morris and Colin Thubron and Norman Lewis, inheritors all of the old imperial gifts of traveling rough without complaint and paying close attention to the very foreign cultures of the world.

In America, I’ve always been impressed and enlightened by the work of P.J. O’Rourke. I’m not especially interested in his politics (and I don’t think he is), and I don’t read him for the humor; but more than almost anyone I know, he has a nose for places, he really does his homework on them, and he just has a worldly intelligence and (what is less often seen) a readiness to be moved that strikes a chord with me. Over and over I’ve gone to El Salvador or Haiti or South Africa or the Philippines, and come home with wonderfully original and different perceptions on the place, only to pick up P.J. O’Rourke and find that he’s said all the same things, only better. And I greatly admire Paul Theroux for his inner travel books — the semi-fictional memoirs (My Secret History, My Other Life, Sir Vidia’s Shadow) in which he undertakes a quite fearless journey into the interior, and all the truths we’d rather not acknowledge, which is to me what travel is really all about.

That’s why my ultimate exemplars and models as a traveler are Emerson and Thoreau, one of whom said that “traveling is a fool’s paradise” and one of whom asked why we should go around the world to count the cats in Zanzibar. And I’ve taken huge inspiration from such descendants of theirs as Peter Matthiessen and Annie Dillard, and from such roving humanists as, say, Ryzsard Kapuscinski and W.G. Sebald.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

Do it for the love. Not for the money (of which there’s very little), not for the travel (which can suffer if what was once a pastime becomes a business), not for the adventure (which sometimes has to go out the window if you’re taking tens of pages of notes on every snack-bar and street- name). And try to think what you in particular have to add or contribute. A million people go every month, no doubt, to the Taj Mahal, and many of them write eloquently about it. What is it that is particular to your interests and experiences that can allow you to say something new? Find a particular angle that arises out of one of your strengths and advantages, and try to make the focus of your piece as narrow and specific as possible. Don’t try to summarize all of Japan after a two-week trip; pick one small corner of it, or one theme (I, for example, took baseball as a theme, a way into Japan, when I first visited, because I knew it would be one world I could understand even without a word of Japanese).

Anyone who goes into travel writing in order to become rich or famous or feted is courting disappointment; anyone in search of huge inner wealth (and challenge and stimulation) should be richly rewarded.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

The rewards of being a traveler (the memories, the freedom, the new friends, the expansion of horizon, the constant refining and undermining of assumptions) combined with the rewards of being a writer (trying to make a clearing in the wilderness and to step out of the commotion and chaos of the world to bring it into a kind of order) squared!

Travel writing has taught me, I think, to look more closely at a place than I would otherwise, to listen more attentively to what’s going on around me and to think more deeply about it, before I leave and after I return. When I go somewhere not to write about it, I often find that the days pass in a blur, and when I return I have vague feelings and recollections, but nothing substantial to hang onto. Very soon it can feel as if I’ve never been there at all. As soon as I’m writing about it, though — usually traveling alone, so as to remain more receptive and open to experience — I’m catching those details in the doorway, or down that alleyway (as a photographer might), I’m forcing myself out to visit places and meet people instead of sitting in the hotel watching CNN, I’m reading and reading about it, trying to come to terms with it. It’s like the difference between a casual conversation and a romance. And as soon as you throw yourself into it in this way you get correspondingly greeted in return. You surrender to a place and it begins to give itself over to you.

Travel has woken me up, in many ways. It’s taught me how provincial I and my assumptions are. It’s expanded my sense of what is possible among human beings and in terms of human kindness (and at times its opposite). And it has shown me a whole other way to live, without a steady prop, not hemmed in by familiarity, and living according to the principles and challenges I most respect.

Best of all, it’s helped me see all of life as a travel, and as an occasion for writing (in order to make sense of it). A few years ago my house burned down, and I lost everything I owned; all my notes, all the books I hadn’t yet completed, all my photos and hopes and letters. And yet traveling helped me see this as a liberation: to live more at home as if I were on the road, to savor the freedom from a past and from possessions, and to think back on all the people I had met, in Tibet and Morocco and Bolivia, who would still have thought of my life as luxurious. Most of the people one meets while traveling deal with more traumas every day than the privileged among us meet in a lifetime. That’s how traveling humbles and inspires.