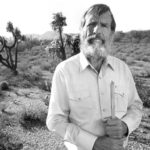

Edward Readicker-Henderson is a contributing editor at National Geographic Traveler and ISLANDS. Writing stories so autobiographical a bio note becomes utterly redundant, he’s won three Lowell Thomas awards, has interviewed kings and shamen, but has never once noodled for flatheads.

How did you get started traveling?

When I was a kid, my Aunt Eleanor worked for the Foreign Service; she’d come back to the states once every two or three years with suitcases full of magic, stuff she’d picked up from around the world, presents from Thailand, Bolivia, India, wherever she was stationed. Stuff I still have. Combine that with a father who got transferred every couple years, I learned early that a) going new places isn’t scary, and b) the whole world is full of really cool stuff to play with.

How did you get started writing?

On a broad definition, according to my mom, even in first grade when I had to make sentences from the spelling words, I turned mine into a story. I would say, though, I started writing in high school to impress a girl. Took about 30 years before she was really impressed, though, which either indicates I was a crappy writer for a very long time or I picked an incredibly tough audience. I never meant to write travel. I wrote poetry and fiction. But more or less by default — there’s no money in poetry and it turned out I write lousy middles in fiction — I started writing travel when I was living in Japan in the late 1980s and early ’90s. That was a boom time for travel writing, although most of it deeply sucked. For every Video Night in Kathmandu or In Xanadu

or Music in Every Room

, there were a hundred books that were an offense to the trees they’d killed. I thought I could do better, I thought I saw a way travel writing could encompass everything I really cared about, but it wasn’t until I read Jeff Greenwald‘s Shopping for Buddhas

that I maybe saw a way I could do it on my own terms. Which is not to say I’ve succeeded, just that I’ve given it my best shot.

What do you consider your first “break” as a writer?

Fast forward ten years or so from Japan. I had done a lot of guidebooks, had sold plenty of pieces to B-level magazines, but really had made no effort to make a living writing. I’d been working as a rare book dealer and had just finished a master’s degree in religious studies — yeah, that’s planning for gainful employment — and needed Something Else To Do when I saw an ad for the Travel Classics writer’s conference. My now ex-wife and I had just refinanced our house, so there was a huge check sitting on the coffee table, and we made a deal: I’d go, and if I didn’t triple what it cost to send me, I’d go get a normal job. If I did triple it, we’d give a serious shot at travel writing being my normal job. My first meeting at the conference was with Arthur Frommer, and he gave me enough assignments in five minutes for me to triple my money. Writing is all I’ve done ever since.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

Surviving airplanes. It’s the only time I envy my brother for being short. After I finally get to the location, it’s a matter of method. A photographer I was working with once called up our editor in a panic. “Edward just sits there,” he said, “and I have no idea what he’s doing.” And then when he finally saw the story, he just said, “Oh. I get it.” I like to go slow and watch what happens around me. And that’s hard to do when you have interviews and sites and things to chase down. The best stories, at least my best stories, come when I’m chased, not chasing. And that takes time, and time is always an issue.

What is your biggest challenge in the research and writing process?

I can easily spend nine or ten months working on a story if the editors don’t start yelling at me to turn it in. A couple hundred drafts. I love rewriting, think it is one of the earth’s great pleasures. After a point, though, it is not a good way to maximize one’s income.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint?

I suck at business. I do no self-promotion at all. I once turned down an invitation to appear on Oprah. I have very few ideas, and the ideas I do have tend to be really complicated, which means I don’t sell as many stories as I should. Once the story is sold, I’m pretty lucky that editors indulge me; they know I’m probably not going to deliver what I told them I would — everything changes — but whatever I do deliver should at least be interesting, and that’s a great luxury. They give me a lot of rope to hang myself with, and they even let me get away with my fondness for adverbs, and I thank every one of them. As for money, let’s face it, if you’re in this for the money, you are a very, very confused person. I make a living, but I live cheap and there are disastrous moments, like when the dog has to have emergency surgery and all the credit cards are full.

Have you ever done other work to make ends meet?

Travel writing was my other work; until it happened, I honestly never expected to make a living writing, just some extra cash for car payments and such. If the internet hadn’t sucked all the fun out of selling rare books — nothing is truly rare anymore, so the sense of ever possible discovery has disappeared — I’d probably still be happily working in bookstores. Selling books was the second best job in the world, and I loved it. Of course, in travel writing, you never lose that sense of ever possible discovery.

What travel authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

Because I started writing poetry, not nonfiction, it’s poets I go to for a reminder of how to play with language and structure: Jack Spicer, John Berryman, Frank O’Hara. Rilke. Lots and lots of Rilke. And Richard Brautigan’s 365-word “I Was Trying to Describe You to Someone,” which has nothing at all to do with travel, may be the most perfect travel story ever written.

For more traditional travel writing, it’s a crime that H.V. Morton is not on everybody’s shelves. His books are masterpieces. Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano should also be required reading. Beyond that, the usual suspects: Chatwin, Theroux, Paul Bowles. As mentioned above, it was Jeff Greenwald’s books that showed me I could write how I wanted to and get away with it — that there was room for poetic weirdness. William Dalrymple’s From the Holy Mountain

makes me scream in envy that I’ll never write anything that good, as does Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

. I’m not sure you can call him a travel writer, but Geoff Dyer, whatever he is, is bloody brilliant. Over the years, I’ve probably read Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard

thirty or forty times, and it still surprises me. Same with Barry Lopez’s Arctic Dreams

. Tim Macintosh-Smith’s books on Ibn Battuta are worth endless re-reads, too. Douglas Mawson for the Antarctic, William Bligh — yes, him, the guy could write — for the Pacific, Aurel Stein for China, Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities

for the crossroads of imagination and reality.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

Buy a time machine and go back to the eighties. It’s your best chance. If you can’t make that work, then give me a reason. Give me a reason to spend my time reading your story instead of doing one of the billion other things I could be doing. Which means having a genuine reason yourself for telling the story. Once you know why you’re doing something, it’s a whole lot easier to do it right. Oh, and have good, generous friends who will kick in their credit cards when the dog needs surgery.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

I go out and play for a living. I write “what I did on my summer vacation” essays for a living. I get to chase down my obsessions, meet incredible people, and, when luck strikes, find a kiosk full of grapefruit gum, and call it work.