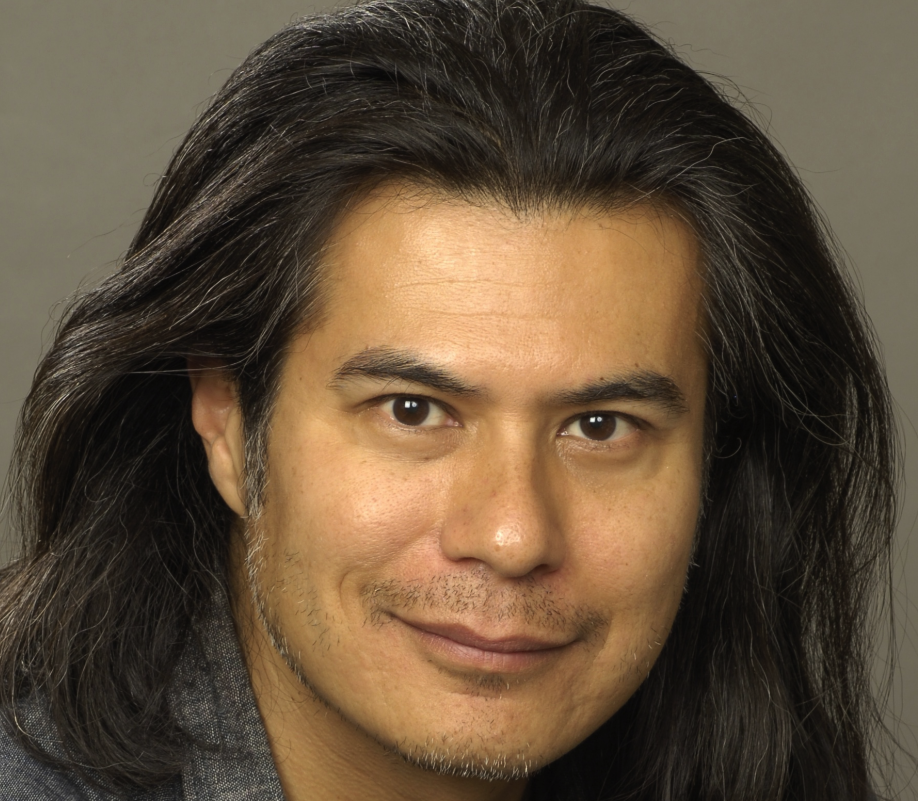

Karl Taro Greenfeld has written three books about Asia; the newest, China Syndrome: The True Story of the 21st Century’s First Great Epidemic, is out this month from HarperCollins in the US and Penguin in the UK. His previous books were Speed Tribes: Days and Nights with Japan’s Next Generation and Standard Deviations: Growing Up and Coming Down in the New Asia. A longtime staff writer and editor for The Nation, TIME and Sports Illustrated, he was also, from 2002 until 2004, the editor of TIME Asia, based in Hong Kong. His work has appeared in GQ, Vogue, Outside, Men’s Journal, The Paris Review, The New York Times Magazine and numerous other publications. His travel writing has appeared in Conde Nast Traveler, Salon, The Wall Street Journal, Details, Arena and TIME among other publications and has been anthologized in The Best American Nonrequired Reading series, Lonely Planet travel books, and others. He currently lives in New York with his wife, Silka, and daughters Esmee and Lola.

How did you get started traveling?

I was born in Japan and then moved to the US when I was still very young—I don’t know if that’s really traveling or not. But we went back to Japan when I was a kid and we moved around quite a bit, from New York to Los Angeles and back to New York again. Again, that’s not traveling but it’s movement, which is at least a component of traveling.

Real travel began for me the summer after high school, when I went to Europe by myself, got ripped off, smoked crappy hash, all that stuff. Very typical. But I did know from a very young age that I wanted to travel. Wait, not really, not “travel”—what I wanted to do was live in different places. And I sort of set up my life so I could do that: Year abroad programs while in college, teaching programs after college, journalism jobs in Japan, Hong Kong, Thailand, summers off in Spain, going to Ashrams in India, even marrying someone of a different nationality. It has all added up my being immersed in many different cultures. That’s sort of how I live.

How did you get started writing?

I don’t think I was good at anything else and I sort of felt I had a little aptitude at this. So after college, when I was living in New York and partying, playing a lot of cards more than anything else, I began to try to freelance a little for magazines: Spy, Harper’s Bazaar, The New York Times Book Review. These were tiny pieces, some of which didn’t even get published, but it gave me some sense of how the whole hustle worked and what my mode might be. I was shy but I figured out early on that I had to psyche myself up so that I could cold call an editor and try to get him interested in me, a story, a subject, so that eventually, maybe not this time but sometime, he would assign a story to me.

Then, after I moved to Japan in 1988, I wrote a novel. I think it was rejected by, like, 10 agents and as many publishers. No one ever published it, but some important people—Joan Didion, David Freeman, Charlotte Sheedy (an agent)—read it and said it was good, so I was simultaneously discouraged and encouraged by that, if that’s possible. I was teaching for a while—hated that—and then got a job at a newspaper, the Asahi Evening News, which I don’t think was read by anyone, and I mean anyone. Our circulation was like four figures, maybe. But it was the kind of place where after a few weeks, I was writing half the newspaper—I would go to these press conferences, people like Dan Quayle or Dick Cheney, the first Bush administration, and write these terrible news stories, and I was reviewing movies, doing huge book reviews. I think I did like a 3,000 word review of two Saul Bellow novellas, for this wierd Japanese newspaper read by old ladies wanting to study English. But I was writing. And I believe that writing, all writing, makes you a better writer.

What do you consider your first “break” as a writer?

While I was at the Asahi Evening News, Victor Navasky, then the editor of The Nation, came to Tokyo. This was around the time that Pantheon Publishers was being acquired, and he gave a press conference at the foreign correspondents club that ended up being about the dire state of the American publishing industry. I grabbed him after the press conference and we talked for a few hours—my mother is a sort of famous writer in Japan, and my father was a successful writer in the US, and these are not insignificant facts in my becoming a writer, and if you want to stop reading here and say I’m a product of nepotism, that’s fine, though I don’t believe that, but then I wouldn’t, would I?—so we talked about the differences between the US publishing biz and Japan’s, and somehow out of that, came a story I did for The Nation in 1991.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

It’s changed as I’ve gotten older. Probably, when I was younger, the biggest challenge was meeting girls or finding a place to score drugs. Now, it’s finding wireless Internet access. In terms of journalism, every story is so different and poses different challenges. These days, the biggest challenge, is when you travel a long way and the person you have come to see doesn’t want to see you, which happens alot with celebrities or Chinese government officials.

What is your biggest challenge in the research and writing process?

Research and writing. Seriously, none of this stuff ever gets any easier.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint? Editors? Finances? Promotion?

I have a family now, so I am always thinking about money, and 90% of the writing I do now is for money. So I guess that’s a reality more than a challenge.

Have you ever done other work to make ends meet?

Not since 1989. Though I suppose journalism might fall into the category of “other work”.

The most interesting period in terms of the peculiarities of making a living from writing was two year period in the early ’90s when I was writing for all the inflight magazines in Asia. This was when Asia was going through its boom and all those magazines: ANA’s Wingspan, Korean Airlines Morning Calm (The Clam, we called it), Cathay Pacific’s Discovery, JAL’s Winds, and a few others were paying decent money — Discovery and Morning Calm were paying like $1500 for stories, Wingpsan would pay like 300,000 yen (about $3000 at the time) and Winds paid the best of all, up to 400,000 for a story, although then Winds changed its rates and paid much less. And you could take the same stories and sell them to several magazines. I had another friend in Tokyo, Christopher Seymour — he went on to write this book Yakuza Diary — and we used to have this sort of assembly line system of writing for inflights. We systematically wrote our way through all the different quaint topics: tea ceremony, Japanese slippers, Thai kickboxing, Sumo wrestling, all the cliches — and tons of little travel stories, but we were bad: we would sometimes write travel articles about places we had never been — and then just crank the stuff out. It was like vocational training for magazine hacks. I learned through sheer volume and repetition how to structure very basic magazine stories, profiles, service pieces. And then, even weirder, after a while, I was able to take some of those stories written for inflight magazines and sell them to real magazines in the US and UK, like Arena, The Face, Details, FHM. It’s sort of like I became really good in that medium — Inflight magazines — and then sort of busted out of that and into the more mainstream magazine world. But I always look back on that period as being this great education in how to make a living as a writer.

What travel authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

The travel books I love are those where there is something at stake. In some ways, the best travel book I’ve ever read is Bernald Diaz des Castillo’s chronicle of the discovery and conquest of Mexico. This guy was a conquistador traveling with Cortez who wrote about the whole invasion of Mexico. Talk about a true clash of cultures, this one with everything at stake. These guys were venturing into the unknown on a chivalric quest and what they were seeing was completely beyond their imaginations—when they go meet Montezuma, the guy is grilling human hearts on a charcoal brazier, how is that for authentic?—so in a way, I think when we travel or write about travel, we are aspiring to a version of that experience.

There is an obscure book called A Beachcomber in the Orient by Harry Foster that I love. It was written in the 1920s and it is astonishing how that guy got through Asia basically on foot. Butterfly Stories by William T. Vollman is a book that, on some level, I have been trying in vain to imitate ever since it came out. My Secret History by Paul Theroux is another one that I think is beyond my own talents as a writer. Red Dust by Ma Jian, Trouser People by Andew Marshall, Balkan Ghosts by Robert Kaplan, You Shall Know our Velocity by Dave Eggers, Imperium and The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapucinski, West with the Night by Beryl Markham—I know, I know, some of these aren’t travel books per se, but they have that spirit.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

Just travel. Have a blast. Get loaded. Meet girls, or boys. Just lose it. And if you still feel like writing despite all the other, better things there are to do in life, then I guess you have no choice.

What is the biggest reward of life as a journalist and travel writer?

When everything goes well and the story or book or article is good enough, then you know what your great reward is? It’s like Ping Pong. You get to do it again.