A 2021 podcast-interview episode about this essay is online here.

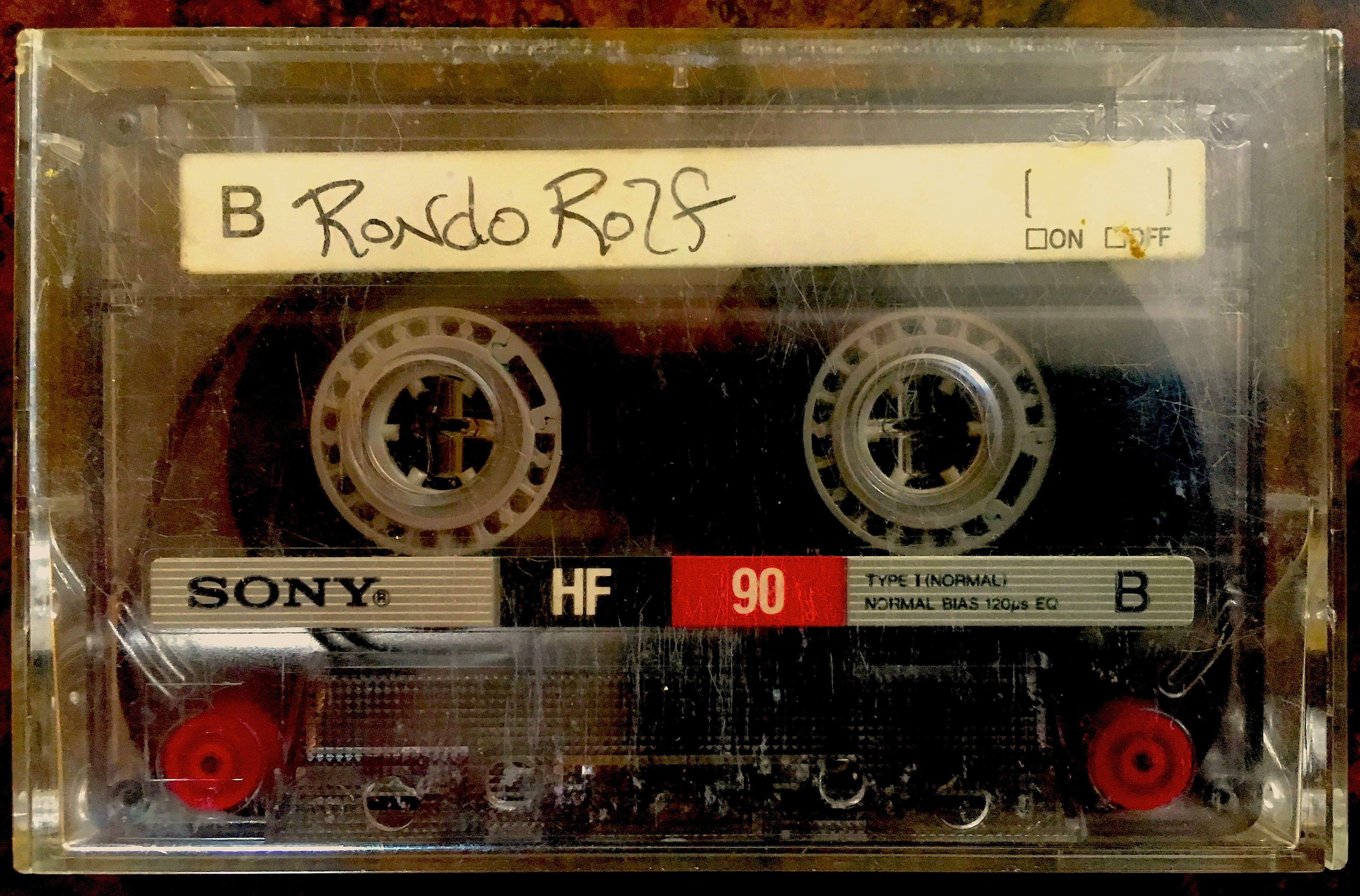

Twenty-five years ago my friend Liesl made me an audiocassette mixtape called Rondo Rolf.

I haven’t owned a functioning tape player for more than a decade, yet I can’t bring myself to throw Rondo Rolf out, since that would be akin to, say, burning a treasured scrapbook or travel-journal. The tape simply contains too many associations to a certain time in my life, both as a physical object and for the songs it contains.

I’ll share the details of those songs (and my thoughts about them) in a moment. But first, in order to properly make sense of what this tape means to me, it’s useful to understand that mixtapes were more than simply a way to share music in the 1980s and 1990s: They were, in fact, a type of extraverbal language — a vivid, inexpensive form of folk communication that flourished in the final two decades of the twentieth century.

I. Why Mixtapes Are, In Practice, a Bygone Art Form

Trying to comprehend mixtapes in retrospect is a little bit like making sense of a dead language: As with, say, Latin, you can suss out literal translations, but you won’t fully understand the conversation as it played out back in the day.

Shared mix-music compilations have continued to thrive in post-audiocassette age — first on burn-CDs, and later as MP3 playlists — but these curated song collections don’t really compare to the person-to-person communication that mixtapes represented. I can think of three primary reasons why this is the case — each of them pegged to a defining limitation of the audiocassette form:

Limitation #1: Music was curated and shared via physical objects

Unlike digital sound files, audiocassette-era music (whether it existed on tapes, CDs, or vinyl) was stored and indexed in the material world. One couldn’t just mix and match tunes on a virtual desktop; a person had to maintain and curate a physical library of music, spend time getting to know specific albums, and cue up a collection of songs that might work well in the mix. This required a hard-won intimacy with one’s music collection.

Moreover, one couldn’t just throw a bunch of tunes together simply because the songs felt right thematically; a mixtape creator had to calculate song-length versus tape-length, finesse the pause-time between songs, and take into account the potential aesthetic pitfalls when a mixtape had to be flipped (or auto-reversed) from Side One to Side Two.

Limitation #2: Information about music could be scarce

One key purpose mixtapes served in the audiocassette era was sharing music that wasn’t available on radio stations or MTV. Sure, one could go to the local music store and find, say, a certain flavor of West Coast hip-hop (or DC hardcore, or vintage rockabilly) that didn’t get played on the radio — but that required money, and this meant that accumulating musical savvy could be a slow and expensive process.

Moreover, one didn’t have the option of typing the name of a song into a search engine and learning more about a given band, or music scene, or sub-genre; one had to subscribe to music magazines and (if a person was savvy enough to even know about them) send off for fan-generated ‘zines and indie-label newsletters. If you lived in a big enough city there might be a free alternative newsweekly with record reviews and band interviews — but my Kansas hometown offered no such option.

Limitation #3: Social networking was an in-real-life undertaking

All of this brings us to an oft-overlooked factor that underpins the bygone aura of mixtapes — and that’s the way they required a social leap-of-faith that was dependent upon in-the-flesh human relationships. Music was not uploaded and downloaded via wireless connections; it was passed from person to person.

This meant that, if you wanted to listen to songs that weren’t on the radio — if you were curious about music that you and your close friends weren’t familiar with — you had to overcome your introversion and seek out people who could help you.

This is how I ended up at Liesl’s mid-town Wichita apartment one December night in the winter of 1991.

II. How It Happened That Liesl Made Me a Mixtape

At this point I should probably back up a bit and clarify that mixtapes weren’t just about introducing people to new music. Oftentimes mixtapes weren’t curated for other people, but to create an ambient soundtrack for, say, studying, or exercising, or taking a road trip. One of the most common uses of the mixtape was to capture and communicate feelings in a romantic relationship (or a potential one) — a practice Nick Hornby, in his 1995 novel High Fidelity, approvingly characterized as “using someone else’s poetry to express how you feel.”

I did not, however, go to Liesl’s place that winter out of romantic interest. Liesl was a longtime family friend (her parents had set up my parents on their first date back in 1967), and she was three years my senior. Whereas I lived in a dorm room at a distant Christian college in Oregon, Liesl had her own apartment, a bevy of hip artist and musician friends, and an intriguingly eclectic music collection. She felt far cooler than me, far more adult. I had no thought of seeking her out as a paramour: I sought her out in the same way one might seek audience with a guru.

I did not, however, go to Liesl’s place that winter out of romantic interest. Liesl was a longtime family friend (her parents had set up my parents on their first date back in 1967), and she was three years my senior. Whereas I lived in a dorm room at a distant Christian college in Oregon, Liesl had her own apartment, a bevy of hip artist and musician friends, and an intriguingly eclectic music collection. She felt far cooler than me, far more adult. I had no thought of seeking her out as a paramour: I sought her out in the same way one might seek audience with a guru.

At the time my musical tastes were undergoing a kind of awakening. I’d grown up listening to a Wichita hard-rock station called T-95, and I enjoyed bands like Led Zeppelin, Rush, AC/DC, U2, and The Police. The first band I saw live was Van Halen, in 1986. Later, in high school, I listened to Metallica and Guns N’ Roses to pump myself up before track races. Then, after graduation, while working at a summer camp in Colorado, a friend introduced me to Jane’s Addiction, an “alternative” band whose music was at once heavy and ethereal. Two summers later I saw Jane’s perform at Lollapalooza alongside a slate of other alternative bands, and I was hooked. When Nirvana shook up the music world with the release of Nevermind that fall, I realized I needed to learn more about what, exactly, alternative music was. So, while back in Kansas on Christmas break, I tracked down Liesl and asked her for guidance.

At first blush it felt like my musical pilgrimage to Liesl’s apartment that December was a failure, since she couldn’t articulate an answer to my queries. I mean this literally. Unlike most Midwesterners, who might offer a pragmatic, if understated reply to my naïve curiosity (i.e. “alternative music is too broad and mercurial to break down categorically”), Liesl was struck dumb: Again and again she would open her mouth, as if trying to address my questions, but no words came out. I went home that night feeling faintly humiliated.

A couple months later, however, a small package bearing Liesl’s handwriting appeared in my campus mailbox in Oregon. Inside was a mixtape called Rondo Rolf — the best answer, she wrote, to what she couldn’t quite explain when I’d paid her a visit over Christmas.

III. Mixtapes Always Evoke More (and Less) Than They Intend

Rondo Rolf didn’t just teach me about alternative music — it illustrated the artistic ethos (and aesthetic dedication) that underpin any serious-minded mixtape. Liesl had written the song titles onto the inside of the J-card, as was standard protocol — but she’d also adorned the outside of the card with a swirl of purple and green watercolors, and come up with a title that riffed on the tape’s content (“rondo” is a musical form featuring a principal theme alternating with contrasting themes). Moreover, she had recruited her boyfriend Michael — a local musician who went on to play in a slew of indie bands (and now owns a hipster donut shop) — to help her select and sequence the tracks.

The danger of putting this much effort into a mixtape is that its recipient won’t properly appreciate what he is being presented with. This was certainly the case with me when I first put Rondo Rolf into a tape deck. In asking Liesl for “alternative music,” I had really just been hoping to hear more bands that sounded like Jane’s Addiction and Nirvana — heavy, melodic, punk-inflected. What I got instead was a collection that mixed alt-pop with noise-rock, party ska with proto-grunge. If a mixtape is (as Nick Horby asserted) akin to receiving a letter from another person, Rondo Rolf featured a type of vocabulary that I couldn’t completely grasp upon first listening to it on my roommate’s dorm-suite stereo.

Had Rondo Rolf arrived as a burn-CD or MP3 playlist I might have skipped past songs that sounded strange to my ears. Since it was spooled out on tape, however, I had to sit through a quirky post-punk song by The Fall before I could hear the Red Hot Chili Peppers; I had to make sense of a Mekons tune before I rocked out to Black Flag. This was, in fact, the charm of listening to mixtapes back then: Though you could attempt to fast-forward, you couldn’t really skip around, and this meant that you listened with a kind of openness and patience that is hard to replicate in the digital era.

If Rondo Rolf has endured as the most affecting mixtape from that era of my life, it could have something to do with its eclectic (yet oddly unified) nature. Unlike the grunge-themed mixtapes I began to receive (and assemble) around the same time, most of the bands on the tape never blended into my regular music rotation. And, because one could not yet learn the story behind a band-name via basic Internet search, I never learned much about many of the songs on Rondo Rolf — I just enjoyed them for how they sounded, how they flowed into (and crashed up against) each other.

In fact, in commenting on the mixtape tracks below, I have employed a degree of online research and retroactive fact-checking that, ironically, might have skewed my experience of the songs as I heard them back in 1992.

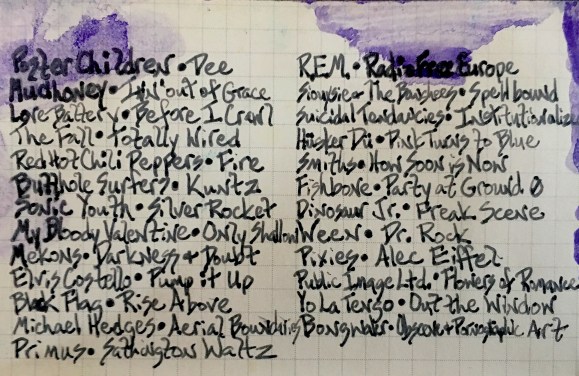

Here’s what Rondo Rolf consisted of:

IV. Rondo Rolf: Side One

1) Poster Children, “Dee“: I don’t know if I properly appreciated it upon first listen, but this anthemic nugget of noise-rock grew on me. Poster Children is a DIY indie outfit from Champaign, Illinois (a fact I didn’t know until I started to write this) and this particular song sets an ambitious tone for the mixtape.

2) Mudhoney, “In ‘n’ Out of Grace”: Mudhoney songs landed on a number of mixtapes I received (and made) in the coming year or two. The whole “grunge” phenomenon was beginning to blow up in the winter of 1991-1992, mainly on the strength of Nirvana’s Nevermind album. As a fuzz-heavy Sub Pop outfit Mudhoney was immediately lumped into the trend, though they never had the same pop sensibility as Nirvana or Pearl Jam (nor the catchy riff-metal grooves that made Soundgarden or Alice in Chains popular). Still, Mudhoney was the quintessence of grunge as it was originally defined — noisy, distorted Pacific Northwest garage punk — and they never deviated from their indie sensibility (despite eventually signing with Reprise Records). The retro-film monologue that opens this song (“we want to be free to ride our machines without getting hassled by The Man!”) comes from a eulogy Peter Fonda’s character delivers in the 1966 Roger Corman movie The Wild Angels.

3) Love Battery, “Before I Crawl” (in the link the song starts at 19:27): Another solid, if lesser-known Seattle band from the Sub Pop grunge stable. Another mixtape I received that winter featured their better-known “Between The Eyes” single (which meant I was versed in at least two of their songs when I saw them open for L7 and Smashing Pumpkins in Portland’s La Luna club a year-and-a-half later).

4) The Fall, “Totally Wired“: This song is a fun, cheeky bit of early-80s British post-punk candy (and, while I enjoyed it on the mixtape, it never occurred to me to seek out any more music by The Fall).

5) Red Hot Chili Peppers, “Fire“: The Chili Peppers eventually became so popular in the years (and decades) that followed that I have recently heard their music referred to as “dad rock.” Music critic Steven Hyden has called their early music “white-boy frat-funk” — but to my 1992 ear they still felt somewhat transgressive, and this punked-up version of an old Jimi Henrix single rocked my socks. The group’s Blood Sugar Sex Magik album was moving the group into the mainstream that winter, so I think Liesl/Michael included this Mother’s Milk track to showcase the raw wackiness that reflected their earlier vibe. It was also around this time that Anthony Kiedis and Flea appeared alongside Andre Agassi in a bizarre Nike tennis commercial, which (despite the predictable “sellout” accusations) I found delightfully weird and entertaining.

6) Butthole Surfers, “Kuntz“: This creepy track from the group’s experimental Locust Abortion Technician album is essentially a Thai folk song run through a warp-distortion machine — and it’s the first track on the Rondo Rolf mixtape that is not in any way listenable. It is faintly funny, however, and I used it as the outgoing message on my telephone answering machine for a few months when I lived in Seattle in 1993.

7) Sonic Youth, “Silver Rocket“: This is a perfect little blistered-indie-rock song, and hearing Sonic Youth for the first time (which, I’ll admit, happened when I first played this mixtape) automatically made me a cooler person. This also led to a weird chain of events, somewhat similar to “single-tracking” (a mixtape-oriented idiosyncrasy I’ll explain in the next entry), wherein you buy a group’s newest album based on the strength of an old mixtape track, but nothing on the new album is as enjoyable as the mixtape song that first turned you on to the band. In this case it was not me but my senior-year roommate who, after listening to Rondo Rolf bought Sonic Youth’s 1992 album Dirty, which we almost never played. (In retrospect it would have made more sense to buy Daydream Nation, so we could have at least listened to “Silver Rocket” over and over.)

8) My Bloody Valentine, “Only Shallow”: This fuzzy/heavy/dreamy indie-noise anthem is close to sonic perfection, and probably my favorite track on the mixtape. It inspired me to go out and buy MBV’s Loveless album on audiocassette, but in the years that followed I mainly just listened to “Only Shallow,” rewound the tape, and listened to “Only Shallow” again. Hence my neologism for this phenomenon: “Single-tracking.” Single-tracking is when you buy an album based on the strength of a mixtape single, but only listen to the album for that single because the rest of the tracks don’t resonate with you in the same way.

9) Mekons, “Darkness and Doubt”: A loopy, slightly bewildering track from the pioneering British-American art-punk band. I never really warmed to it, but every indie-rock mixtape needs an arbitrary nod to genre-pedigree, and on Rondo Rolf this was it.

10) Elvis Costello, “Pump It Up”: I had known Elvis Costello by reputation, but this was my first real exposure to his music. This song is a bass-driven party-rock groove — and it’s one of my favorite tracks on the mixtape.

11) Black Flag, “Rise Above“: I was familiar with Black Flag from having watched a VHS copy of Penelope Spheeris’ seminal (and, for me, hugely educational) Decline of Western Civilization documentary, which chronicled LA’s early-80s punk scene. I had also seen Henry Rollins perform at Lollapalooza the previous summer, But, somehow, I’d never heard “Rise Above” until Rondo Rolf. It remains my favorite Black Flag song (and one of my favorite songs from that punk era in general).

12) Michael Hedges, “Aerial Boundaries“: This ambient-acoustic number sounded so different from the previous tracks that I typically just flipped the tape over before the song began, rewound the remaining slack, and started Side Two.

12b) Primus, “Sathington Waltz“: I don’t even count this as a full Rondo Rolf track, since (as was the case with so many mixtapes) the tape cut off a third of the way through this trippy instrumental song.

V. Rondo Rolf: Side Two

13) R.E.M., “Radio Free Europe“: At the time R.E.M. was a legitimate mainstream radio-rock band, after Document (1987), Green (1988), and Out of Time (1991) all charted singles in the Billboard 100. “Radio Free Europe” is the first track off of Murmur, the band’s 1983 debut, and I think Liesl/Michael included it as a nod to the band’s (excellent) early work.

14) Siouxie and the Banshees, “Spellbound“: This is possibly the only Rondo Rolf track I’d listened to several times before receiving the mixtape. I wasn’t necessarily a Siouxsie diehard, but I was familiar with her early work (because someone had dubbed the Once Upon a Time compilation for me), and I had enjoyed her Lollapalooza performance at Sandstone Amphitheater the previous summer.

15) Suicidal Tendencies, “Institutionalized”: This ingenious SoCal skate-punk ode to teenage-male mental health is the most memorably hilarious song to come out of the 1980s hardcore scene. There were kids at my high school who were into thrash music, and I was faintly aware that this song existed, but I never fully appreciated it until Rondo Rolf. I later re-embraced it when I bought the Repo Man soundtrack some years later — and to this day the song (and even the video) feels timeless.

16) Husker Du, “Pink Turns to Blue“: This is the second Rondo Rolf song that resulted in a case of “single-tracking”: My senior-year roommate bought the iconic Zen Arcade album on the strength of “Pink Turns to Blue,” but it’s the only Zen track we listened to on a regular basis.

17) The Smiths, “How Soon is Now”: Another near-perfect song — and my first real introduction to The Smiths (who I previously only knew by reputation). I never became a Smiths fan in the buy-all-their-albums sense, but I listened to their Best…I compilation countless times during my eight-month Vanagon journey around North America in 1994 (and I still consider it one of the finest “greatest hits” albums by any band of the era — though this could be tied in to the fact that it invariably reminds me of my first vagabonding journey).

18) Fishbone, “Party at Ground Zero”: In an earlier post I mentioned that there are a handful of songs (including Thrill Kill Kult’s “Sex on Wheels” and Cypress Hill’s “Hits From the Bong”) that will lift my spirits under most any circumstances. “Party at Ground Zero” has become one of them. I initially sought out “alternative” music because I liked heavy, distorted rock (a yen that the nascent grunge trend would address in spades), but this off-the-hook party-ska song blew my mind upon first listen. It is — at both the lyrical and the musical level — an ingenious (and joyous) piece of Cold War-era party-pop songwriting.

19) Dinosaur Jr., “Freak Scene“: This was a solid song, and a lot of 1990s indie-rock traces its way back to Dinosaur Jr., but in practice I tended to end Rondo Rolf after the emotional high of the Fishbone song. Years later, when I was living in Korea, an expat friend turned me on to Lou Barlow’s Dinosaur Jr-spinoff band Sebadoh, whose album Bakesale remains one of my favorite indie albums of the 1990s.

20) Ween, “Dr. Rock“: This art-punk tune, while enjoyable enough, also suffered from the fact that I’d usually stopped listening to the mixtape by this point.

21) Pixies, “Alec Eiffel“: Rondo Rolf may well be most notable for the fact that it piqued my interest in the Pixies, who became one of my favorite bands in the years that followed. I bought the group’s 1991 album Trompe Le Monde that winter, and it went into heavy rotation on the dorm room stereo (which, for the most part, precluded my need to listen to the Pixies on side two of this mixtape). Earlier Pixies offerings — and 1989’s Doolittle in particular — soon joined the dorm-room rotation.

22) Public Image Limited, “Flowers of Romance“: See #20 above. Despite my musical ignorance at the time, I was aware that PiL was the post-punk descendent of Johnny Rotten and the Sex Pistols (a band I retroactively embraced after — and this is no joke — reading Greil Marcus’s book Lipstick Traces in 1990).

23) Yo La Tengo, “Out the Window“: See #20 above. I got into Yo La Tengo in earnest a decade later, on the strength of a different mixtape, while traveling in Asia. As a result, the band’s 1997 I Can Hear the Heart Beating as One is a personal favorite.

24) Bongwater, “Obscene and Pornographic Art“: This brilliant — and very funny — psychedelic/experimental song made a nice end-note to the mixtape.

VI. Postscript

One final thought about mixtapes is that while they initially serve as a kind of communication between two or more people, they usually end up becoming one of the ways that you communicate with yourself over the course of many years. Rondo Rolf might have influenced just a few small aspects of my musical taste (and music was itself just one small aspect of how I made sense of the greater world), but listening to it now reminds me of exactly what it felt like to be 21 years old and curious about what life had in store.

In the months and years after the winter of 1991-1992 I must have created and shared several dozen mixtapes of my own. Oddly enough, I don’t remember those tapes very well, since I gave them away without making copies for myself. But perhaps someone, somewhere, still listens to those songs as a way of conversing with the person they once were, and wanted to become.

Update: For those wanting way to hear these songs in a single online stream, one of my Twitter followers, Padraig Finnerty, has created a Rondo Rolf playlist at Spotify.

Note: I don’t host a “comments” section, but I’m happy to hear your thoughts via my Contact page. To learn more about what this blog is all about, read items #2 and #3 from my recent update post.