Exactly twenty years ago I was entering my fourth month of living as an expatriate English teacher in Pusan (a.k.a. Busan) South Korea. This was my first experience of living in another country, and those first few months were difficult — partly because of culture shock, partly because of what-the-hell-am-I-doing-in-life mid-twenties crisis, and partly because I’d first arrived in the seasonal-affective gloom of a cold and dark winter.

Adding to the disorientation was the fact that my host country was, in the mid-1990s, in the throes of segyehwa (세계화) — i.e. the uniquely Korean embrace of globalization. Whereas countries like the United States globalized incrementally over the course of decades (with the help of immigrant populations and far-ranging overseas enterprise), once-isolated Korea seemed hell-bent on globalizing its culture and economy over the space of a few years. The fact that someone like me — young, unqualified, utterly clueless — could find well-paying work teaching English in Pusan spoke to the Korea’s thirst for global-minded exchange and education.

Hence, when I arrived in Korea, I wasn’t just experiencing the traditional aspects of Korean culture — I was getting a crash-course in a culture that was itself embracing a broad array of international influences, many of them Western-oriented. In this way, trying to comprehend my host culture was complicated by the fact that my host country seemed to be reinventing itself with each passing week.

For me, the most startling symptom of Korea’s haphazard embrace of segyehwa was the fact that, when I first arrived in the city, all the nightclubs in Pusan played eurodance music. At the time I didn’t even realize that the music in question was called “eurodance” (I usually characterized it as “that cheesy disco shit”); all I knew was that, a) I despised it, and b) you couldn’t go into a Korean nightclub — even a grungy, expat-filled dive-bar — without hearing it.

For me, the most startling symptom of Korea’s haphazard embrace of segyehwa was the fact that, when I first arrived in the city, all the nightclubs in Pusan played eurodance music. At the time I didn’t even realize that the music in question was called “eurodance” (I usually characterized it as “that cheesy disco shit”); all I knew was that, a) I despised it, and b) you couldn’t go into a Korean nightclub — even a grungy, expat-filled dive-bar — without hearing it.

Having just spent the previous half-decade in the flannel-lined mosh-pits of Grunge America (which was, by that point, very much on the wane), I was somewhat of a music-snob when I arrived in Korea. Grunge came with its own ethos of authenticity, and while American “alternative culture” theoretically embraced non-rock music (hip-hop, ska, alt-country, funk, revival-swing, etc.), the candy-corn disco-vibe of eurodance felt like the antithesis of everything I had come to love about music.

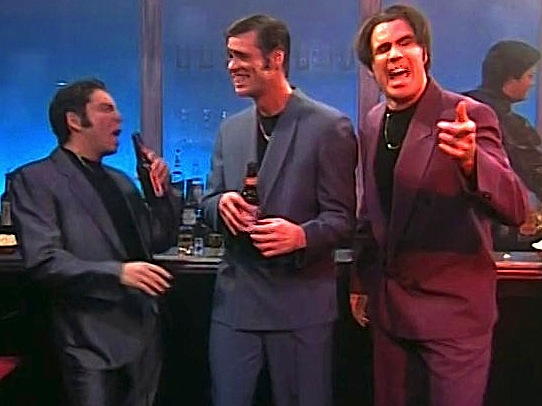

I certainly wasn’t alone in this sentiment. For years the disgraced German eurodance group Milli Vanilli had been a metaphor for everything that was fake about overproduced pop music, and the most memorable Saturday Night Live sketch of 1996 had been Chris Kattan and Will Ferrell’s “Roxbury Guys” — a pair of coked-up, rayon-suited nitwits who skulked from nightclub to nightclub bobbing their heads in unison to “What Is Love” by Trinidadian-Dutch eurodance artist Haddaway.

Music snobbery (and Milli Vanilli) aside, some eurodance songs did find success on the U.S. pop charts in the nineties — from “The Power” by Germany’s Snap! in 1990, to “The Sign” by Sweden’s Ace of Base in 1994, to the execrable “Barbie Girl” by Norway’s Aqua in 1997. Whereas American audiences would intuit that those songs belonged to a very specific sub-set of European pop music, however, Korean audiences in the mid-1990s were less inclined to differentiate eurodance from swingbeat, punk rock from pop rock, hip-hop from R&B. In Pusan, in 1997, it was all considered “Western music,” and the average Korean enjoyed it less for the specificity of its origin (or the authenticity of its production) than for how enjoyable it sounded on repeat listening.

Music snobbery (and Milli Vanilli) aside, some eurodance songs did find success on the U.S. pop charts in the nineties — from “The Power” by Germany’s Snap! in 1990, to “The Sign” by Sweden’s Ace of Base in 1994, to the execrable “Barbie Girl” by Norway’s Aqua in 1997. Whereas American audiences would intuit that those songs belonged to a very specific sub-set of European pop music, however, Korean audiences in the mid-1990s were less inclined to differentiate eurodance from swingbeat, punk rock from pop rock, hip-hop from R&B. In Pusan, in 1997, it was all considered “Western music,” and the average Korean enjoyed it less for the specificity of its origin (or the authenticity of its production) than for how enjoyable it sounded on repeat listening.

Eurodance made its way into Korea not on the strength of individual artists’ albums, but through an ongoing series of mix-CDs called Club DJ Dance Music, which BMG Korea began to release in 1995. Each mix-CD featured 10-12 songs by eurodance acts like La Bouche and Playahitty (as well as the occasional dance-pop song by the Spice Girls or Backstreet Boys); the cover art featured faintly racist hip-hop graffiti-caricatures of giant-lipped Afro-European DJs. One could find these CDs for sale at most any music store in Pusan alongside Michael Jackson albums and non-dance genre-compilations like Warner Korea’s Punk NRG (which, in addition to the incongruity of having the disco term “NRG” in its title, is probably the only commercial punk collection to place Sugar Ray alongside Johnny Thunders and the Ramones).

I don’t think I fully appreciated at the time just how momentous it was to experience this chaotic moment in Korean music history — a time when music still traveled by CD, the dial-up internet was just catching on, and the seeds of Korea’s nascent K-Pop explosion were being sown. I might have hated the endless rotation of eurodance songs in Pusan’s nightclubs, but there were many young Koreans who hated “Western music” in general — not just for the way it sounded, but for the way it threatened to dilute traditional Korean culture. An American friend of mine fronted a punk-inflected rock-band called Cricket Power, and one of his shows outside the gates of Pusan National University was disrupted when a drunken student grabbed the mic and started ranting to the crowd about the evils of foreign influences in Korea.

Part of the problem underlying that particular incident was that the Korean economy was beginning to slump in tandem with the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and some Koreans were doubting the wisdom of embracing segyehwa at any level. So far as I could tell, however, the young Koreans I was getting to know were embracing foreign influences on their own cultural terms. Many of them may have jumped into the mosh-pit during Cricket Power’s heavier songs, for instance, but they would assiduously bow to their seniors (in the customary Korean style) the moment the song had finished. Moreover, in an era when a wealth of international music was not yet readily available online, attending a punk show or gyrating to eurodance tunes was, for Koreans, less a matter of declaring one’s taste than sampling the new wealth of musical variety on offer.

Part of the problem underlying that particular incident was that the Korean economy was beginning to slump in tandem with the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and some Koreans were doubting the wisdom of embracing segyehwa at any level. So far as I could tell, however, the young Koreans I was getting to know were embracing foreign influences on their own cultural terms. Many of them may have jumped into the mosh-pit during Cricket Power’s heavier songs, for instance, but they would assiduously bow to their seniors (in the customary Korean style) the moment the song had finished. Moreover, in an era when a wealth of international music was not yet readily available online, attending a punk show or gyrating to eurodance tunes was, for Koreans, less a matter of declaring one’s taste than sampling the new wealth of musical variety on offer.

One of the first Korean-made recordings that captured my imagination that year was by the group Seo Taiji & Boys, which mixed Pantera-style thrash-metal with NSYNC-style dance pop, Bon Jovi-sounding balladry with Cypress Hill-sounding gangsta rap — often in the same song. Seo Taiji & Boys split up not long before I arrived in Korea, but a former group member named Yang Hyun-suk had recently founded YG Entertainment, which (along with SM Entertainment and JYP Entertainment) would come revolutionize Korean popular music. By the late 1990s, as eurodance music was morphing into progressive house (and fading from European pop charts), what became known as “K-Pop” began to transform the way popular music was consumed by teenagers and young adults in East and Southeast Asia.

Though the K-Pop moniker technically applies to all genres of popular music in Korea, it is, in practice, a direct offshoot of the segyehwa-flavored musical miscegenation that I witnessed upon arrival in Pusan twenty years ago. And, while eurodance might best be remembered in America for SNL skits and lip-synch scandals, its influence suffuses K-Pop’s predilection for synthesizer riffs, bass-heavy beats, melodic vocals, rapped verses, English-language lyrics, and exacting studio production. K-Pop superstars like Psy might have still existed without the influence of eurodance music, but songs like “Gangnam Style” wouldn’t have sounded quite the same.

I ended up living in Pusan for two years. By the time I left, in late 1998, I had actually come to regard eurodance music with a kind of nostalgia — not for the memory of half-heartedly grooving to it when I first arrived in Korea, but for the way it reminded me of how vulnerable and off-kilter I felt during my first few months in the country. In a way, the bile I’d felt toward eurodance redirected any negative feelings I might have had for Korea in general, and — strangely enough — the more I came to enjoy my time in Korea, the more I made peace with the (admittedly catchy) rhythms of eurodance. One of my last acts before leaving the country was to buy a cassette copy of Club DJ Dance Music.

I ended up living in Pusan for two years. By the time I left, in late 1998, I had actually come to regard eurodance music with a kind of nostalgia — not for the memory of half-heartedly grooving to it when I first arrived in Korea, but for the way it reminded me of how vulnerable and off-kilter I felt during my first few months in the country. In a way, the bile I’d felt toward eurodance redirected any negative feelings I might have had for Korea in general, and — strangely enough — the more I came to enjoy my time in Korea, the more I made peace with the (admittedly catchy) rhythms of eurodance. One of my last acts before leaving the country was to buy a cassette copy of Club DJ Dance Music.

By this time the Club DJ Dance series was much harder to find than it had been in 1996. I ended up settling for a pirated version that featured songs by 23 eurodance artists, including Afro-Belgians (Bizz Nizz), German-Latinos (No Mercy), Nigerian-Swedes (Dr Alban), a white Swede (E-Type), a DJ from Switzerland (DJ Bobo), and two acts (La Bouche and Le Click) created by the same guy who had produced Milli Vanilli. All in addition to a dance track by hip-hop pioneer Afrika Bambaataa, pop hits from the Spice Girls and Backstreet Boys, and the original Andalusian version of “Macarena.” Taken together, these tracks constitute the weirdest tape I still keep in my (increasingly anachronistic and unplayable) cassette collection.

Critic Terry Teachout has noted that the earliest wave of rock-and-roll tended to be a “rhythmically exhilarating but otherwise simple-minded accompaniment to social dancing… of [retrospective] interest only to septuagenarians who met their spouses at Eisenhower-era sock hops.” As a Gen-X fan of vintage rock I don’t know that I entirely agree with that statement — but it feels like the sentiment can be applied to a later generation of club tracks by eurodance artists like Ice MC and T.O.F.

Indeed, when I think back to the songs on Club DJ Dance Music, I don’t reflect much on their role in pop-music history; I mainly just marvel at how the soundtrack to my first months in Asia 20 years ago consisted of upbeat, overproduced Afro-European electronic dance tunes (and how strangely fitting, in retrospect, that was).

Club DJ Dance Music (Pusan Pirated Version): Side One

1) Poco Loco: Come Everybody

2) Meli Melo Featuring Miss Hélène: La Danse d’Hélène

I never cared for this song because it wasn’t particularly danceable (unless you were being ironic), and it sounded like a kids’ song — a detail which is borne out by the bizarre French TV video above. I don’t think I was fully aware, back in the 1990s, that this was a dance-pop version of “The Hokey Pokey.”

3) Bizz Nizz Ft. George Arrendell: Dabadabiaboo

4) N. Reagan: The Dance of Love

5) Joan & John: Jungle

6) Ice MC: Music For Money

7) E-Type: So Dem A Com

8) DJ Bobo: Everything Has Changed

9) No Mercy: Where Do You Go

10) Backstreet Boys: We’ve Got It Goin On’

11) Sweetbox: Shakalaka

This gritty, catchy dance groove is probably by favorite song on the tape. Sweetbox was formed by German music producers in the mid-1990s, and has had a rotating lineup of female vocalists. Michigan-born Dacia Bridges is the singer on this track; she left the group in 1996.

12) Magic Vision Feat. MC Soccer: NaNa HeyHey

Club DJ Dance Music (Pusan Pirated Version): Side Two

13) Real McCoy: One More Time

One of the more globally popular eurodance acts of the 1990s, Real McCoy was formed in Berlin, and its live performances tended to rely on lip-synching tracks that were recorded by other vocal talent (as had been the case with Milli Vanilli).

14) Spice Girls: Wannabe

15) Afrika Bambaataa: Feel the Vibe

16) Le Click: Tonight Is The Night

17) La Bouche: Be My Lover

18) Dr Alban: Let The Beat Go On

19) T.O.F: Funk It Up

This is another of my favorite tracks from the tape. T.O.F was an Afro-Dutch rapper; his acronym stands for The Original FlyGuy.

20) Playahitty: 1-2-3!

21) Los Del Rio: Macarena

22) Mecanic MC’s: Rap All Chant

23) Ice MC: Think About The Way

Note: I don’t host a “comments” section, but I’m happy to hear your thoughts via my Contact page. To learn more about what this blog is all about, read items #2 and #3 from my recent update post.