1) On the intrinsic human urge to travel

The wish to travel seems to me characteristically human: the desire to move, to satisfy your curiosity or ease your fears, to change the circumstances of your life, to be a stranger, to make a friend, to experience an exotic landscape, to risk the unknown, the bear witness to the consequences, tragic or comic, of people possessed by the narcissism of minor differences. Chekhov said, “If you’re afraid of loneliness, don’t marry.” I would say, if you’re afraid of loneliness, don’t travel. The literature of travel shows the effects of solitude, sometimes mournful, more often enriching, now and then unexpectedly spiritual.

2) On why travel is still essential

In the course of my life, travel has changed, not only in the speed and efficiency, but because of the altered circumstances of the world — much of it connected and known. This conceit of Internet-inspired omniscience has produced the arrogant delusion that the physical effort of travel is superfluous. Yet there are many parts of the world that are little known and worth visiting, and there was a time in my traveling when some parts of the earth offered any traveler the Columbus or Crusoe thrill of discovery.

3) On the ancient origins of travel narratives

The travel narrative is the oldest in the world, the story the wanderer tells to the folk gathered around the fire after his or her return from a journey. “This is what I saw” — news from the wider world; the odd, the strange, the shocking, tales of beasts or of other people. “They’re just like us!” or “They’re not like us at all” The traveler’s take is always in the nature of a report. And it is the origin of narrative fiction too, the traveler enlivening a dozing group with invented details, embroidering on experience.

4) On what makes a good travel book

The writing of a travel book is, like the trip itself, a conscious decision, requiring a gift for description, an ear for dialogue, a great deal of patience, and the stomach for retracing one’s steps. It is very different from fiction, the inner journey, which is an imaginative process of discovery. In the travel book, the writer knows exactly how the story will end; there are no surprises. The privations of the road become the privations of the desk. Because the travel book is a recounting of the journey, there is always the chance that the traveler will embroider, for effect or merely to stay awake.

5) On commonplace urban dangers

Apart from some obvious hellholes — Mogadishu, Baghdad, Kabul — every city has its high-risk neighborhoods. It is in the nature of a city to be alienating, the hunting ground of opportunists, rip-off artists, and muggers. I once asked a concierge in a large hotel near Union Square in San Francisco for directions to the Asian Arts Museum. Though it was within walking distance, he begged me to take a taxi, to speed me past the streets of panhandlers, homeless people, decompensating schizos, and drunks, In the event, I walked — briskly — and was not inconvenienced.

6) On the notion of happy places

Are there truly happy places? I tend to think that happiness is a particular time in a particular place, an epiphany that remains as a consolation and a regret. Fogies recall many a happy time, because fogeydom is the last bastion of the bore and reminiscence is its anthem. Ordering food in a restaurant in the 1950s, William Burroughs said, “What I want for dinner is a bass fished in Lake Huron in 1927.”

7) On the merits of traveling on foot

Walking to ease the mind is also an objective of the pilgrim. There is a spiritual dimension too: the walk itself is part of the process of purification. Walking is the age-old form of travel, the most fundamental, perhaps the most revealing.

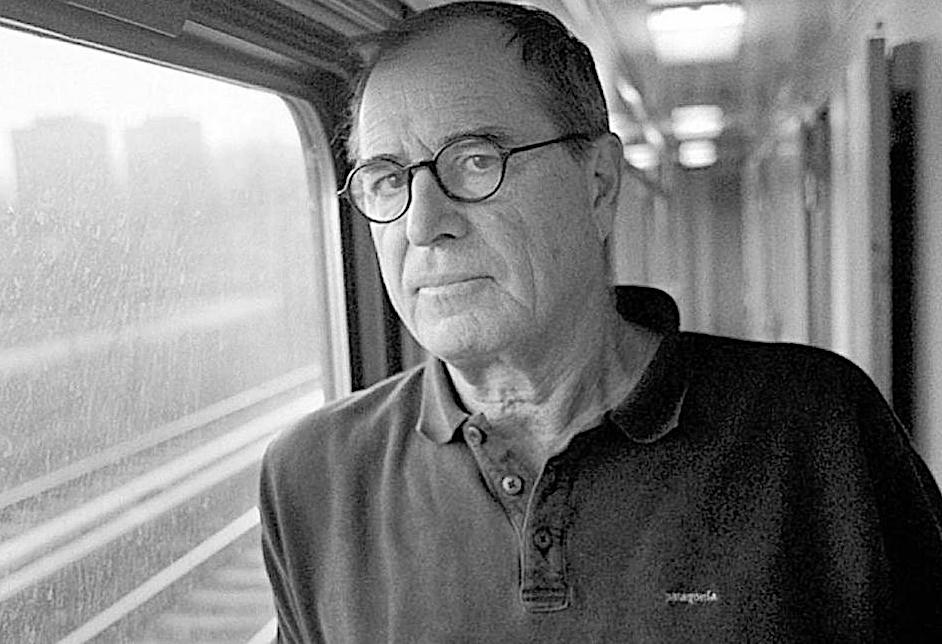

8) On the merits of traveling alone

I have always traveled alone. With the exception of large-scale expeditions involving a crew or a team, every other kind of travel is diminished by the presence of others. The experience is shared — someone to help, buy tickets, make love to, pour out your heart to, help set up the tent, do the driving, whatever. Although they do not usually say so, many travelers have a companion. Such a person is a consolation, and inevitably a distraction.

9) Theroux’s ten prescriptions for a meaningful journey

- Leave home

- Go alone

- Travel light

- Bring a map

- Go by land

- Walk across a national frontier

- Keep a journal

- Read a novel that has no relation to the place you’re in

- If you must bring a cell phone, avoid using it

- Make a friend