1) Vacations as we know them began in the mid-twentieth century

Long enjoyed by the leisure class, vacationing was an unknown practice to most Americans at the turn of the twentieth century. Yet by midcentury, paid leave periods, carved out for the explicit purpose of giving individuals the chance to get away for a while, had become an expectation for white- and blue-collar workers alike. Even if many middle-income people couldn’t travel, paid leave at least made it a possibility. Vacations, then, were not only a highly visible part of the Fordist good life that flowed from business, labor, and government’s cooperative pursuit of mass consumption but were metaphoric for the expanding life possibilities brought into view by a more equitable economic order.

2) “Staycations” may well have had their start during World War II

To conserve resources but still allow for reinvigorating vacations, family economists recommended “a new pattern of recreation” centered around the home. E. DeAlton and Nell Partridge of the Montclair State Teachers College advised Americans to build “recreation kits” from materials around the house. In lieu of an auto trip, old magazines and a pair of scissors could keep children occupied for hours, while broomsticks came in handy for a game of driveway shuffleboard. Many Americans followed such a program, staying put to work on their homes, tend gardens, and host barbeques. The turn toward home vacations meant a record year for the lawn furniture industry, before the war agencies one by one appropriated its production materials. Although the war agencies favored activities around the home and local communities, most recognized that many Americans were determined to travel. In this case, the best they could do was urge tourists to minimize the strain they put on travel infrastructure. “Vacation at home. If you must ‘get away,'” begged ODT head Joseph B. Eastman, “go somewhere near home and begin and end the trip … to avoid weekend travel peaks. And don’t move around; go to one place and stay there.” Some suggested that tourists use public carriers to explore nearby towns. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, for instance, noted that Camden was just a ferry ride away. The ideal trip, then, was one that didn’t involve an automobile and didn’t tie up needed space on transcontinental railways.

3) The postwar travel boom was being planned while WWII was still happening

Across the Atlantic, the British Travel Association announced an eight-point program in late 1944 to attract postwar tourists. And on the Continent, no sooner could Allied armies liberate a city than American Express opened a new office there. Along with laying the preparatory groundwork, companies developed new products to roll out in peacetime. The Pullman Car Company launched a massive redesign campaign. Railroads across the country developed plans for Vista- and Astra-Domed cars that offered a dazzling view of passing scenery. Others tweaked the minutia of postwar operations. United Airlines carried out extensive market research to guide the interior design of new aircraft, probing consumers’ thoughts on seating, legroom, lighting, sleeping berths, cocktails, and dozens of other considerations. The structure of the international airline industry was the biggest issue to resolve. Anticipating a boom, American analysts early on eyed international air routes, along with oil, as the two main points of contention facing allies and foes alike after the war.

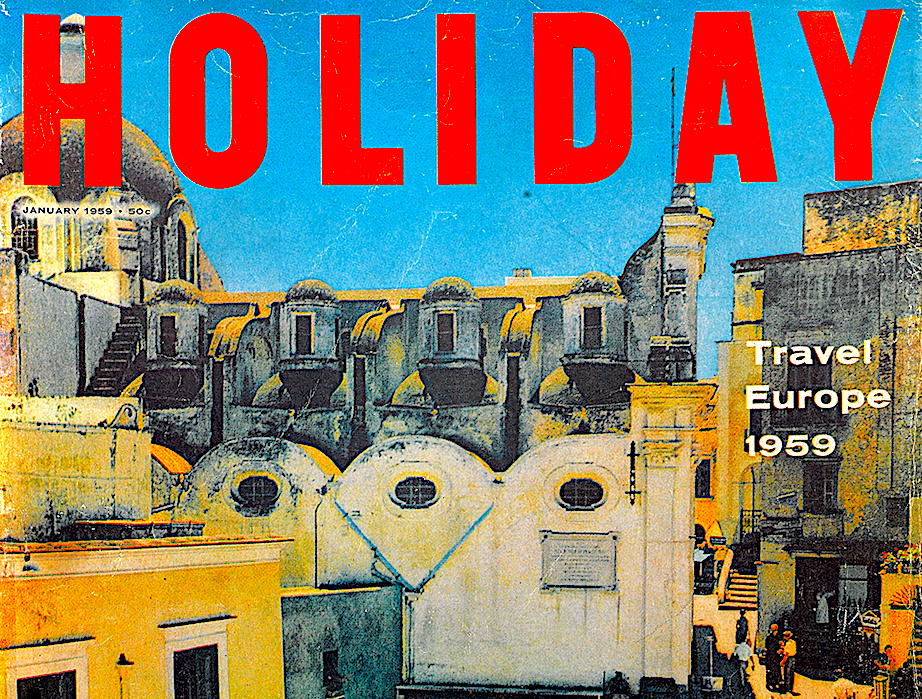

4) Magazines were key to popularizing the twentieth-century travel boom

Magazines played a unique role in making and marketing the travel boom. As the main conduit for the seductive travel ads that beckoned consumers to far-off places, they mediated between the vacation industry and the vacationing public, translating the former’s market growth imperatives into the latter’s desire for a more leisured way of life. Though magazines were challenged by the giant that the television industry was fast growing into, they still occupied a unique storytelling role in postwar American culture. Blending image and text in news reports, narratives, and social commentary, they provided shape to the issues and trends playing out around readers. Further, magazines offered an avenue for imagining a national, middle-class identity, as readers could see what American culture looked like, knowing that millions of unknown peers in distant neighborhoods like their own were doing the same. Every week or month, magazines conjured up an image of a nation on the move, dashing from one vacationland to the next. And as the tourism industry grew larger and its ad budget swelled, publishers became more and more motivated to feature the stories that could connect travel marketers with travel-minded audiences.

5) Travel-magazine advertisements shaped travelers’ expectations

Travel ads and articles offered frameworks for imagining what it meant to inhabit a wider world, to break out of everyday life’s stultifying routines, to be well traveled, to make contact with others, and to see the places that had long captivated one’s imagination. In the same manner, they helped answer questions about what satisfactions to glean from vacation travel: relaxation or stimulation? Education or fun? Refinement or self-actualization? As the answers that marketers suggested subtly shifted over time, we can gradually see a whole touristic sensibility toward social experience, or what Zygmunt Bauman has called the “sensation-gatherer’s life: come into focus. Exploring changes in the tourist imagination thus offers insight on how leisure choices, consumption, life experiences, and notions of identity became more tightly fused in the mid-twentieth century.

6) Class-mobility was central to how travel was marketed at mid-century

Tourism’s experiential nature lent itself in advertisers’ hands to narratives of transformation that pivoted on acts of social transcendence, such as crossing class borders or breaking away from the tourist crowds. Moreover, magazines like Holiday and Sports Illustrated urged marketers to pursue audiences that, while quantitatively smaller than the mass market, were qualitatively more inclined to splurge. As market researchers embraced this approach, closely training their sights on tastes and dispositions, vacationing showed itself an easy means to differentiate people who had previously been lumped together in the great middle-income market and reorder them hierarchically along lifestyle lines. In terms of tourism, marketers came to see characteristics at the heart of travel, such as a joie de vivre and a longing for authenticity, as an analogue for stylized ways of living built on specialty consumption.

7) Ebony encouraged Jim Crow-era black travelers to go overseas

The Jim Crow discrimination that confronted black travelers went practically unmentioned in mainstream popular magazines but was treated at length in Ebony. By directing African American vacationers to sites and establishments where they were less likely to face prejudice, Ebony supplemented specialized travel literature like the Green Book and Travelguide, offering a resource to readers who wanted to participate in the vacation boom without facing the indignity of slammed doors, hateful stares, and venomous epithets. Given that black vacationers encountered prejudice from South Carolina to Southern California, foreign travel was portrayed as a particularly liberating experience. Leaving behind the nation that instituted and upheld Jim Crow, African Americans could, according to this narrative, cast off the shackles of racial prejudice. France, in particular, had long been viewed as a refuge where African Americans could expect to be treated as equals. But Ebony pointed out that black Americans were shown more dignified treatment than they could expect at home in many other nations. Mexico, for instance, was a “Racial Oasis South of Dixie.”

8) Quirky travel “stunts” were a part of mid-century travel media

Capriciousness was a theme taken up in other forms as well. Life profiled an American Automobile Association (AAA) employee who traveled around the United States in 1949, visiting small towns named for European cities. One tour through Pennsylvania and New York netted him London, Belfast, Rome, Milan, Athens, Moscow, Odessa, Naples, Cadiz, Warsaw, Riga, Venice, Paris, Berne, Berlin, Vienna, Copenhagen, Lisbon, Madrid, and Amsterdam. Another traveler profiled by Life, John Nichols, was photographed striking a headstand in front of every state capitol building. The following year, Nichols crossed the country again. This time he posed in front of state road markers with a local culinary specialty in hand. In Manhattan, Nichols posed with a Manhattan. In Texas, he feasted on a bowl of chili. These articles were in part novelty stories. But they also spoke to the sheer joy of being able to go where one pleased on nothing more than a whim. Within the broader vacation boom context, the stories pointed out that the freedom to play, or derive pleasure out of life as a worthy pursuit in and of itself, was a distinct aspect of American culture. The capriciousness at the heart of irreverent mobility and colorful sportswear reflected play in its purest form, imbuing culture with a larger animating spirit fun. When much of the world was embroiled in painful reconstruction and violent political struggle, fun for its own sake could be made into a powerful testament to the American system.

9) Some mid-century employers toyed with the idea of yearlong vacations

Aware of the great appeal of long stretches of free time, some companies even began experimenting with year-long vacations. Holiday profiled a Chicago advertising firm that gave employees twelve months off on a rotating basis to travel the world. In the blue-collar fields, members of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers at a Chicago plant negotiated a full year’s vacation for those with ten years of service. While yearlong vacations remained an oddity, they were the exception that proved the rule. They suggested that in the near future the “twelve-month sabbatical” might join well-established and distinctly American temporalities like “two weeks with pay.” But more than that, stories that highlighted the temporal aspects of vacationing identified American society as one that afforded individuals unique control over that most precious resource: time.