(And why this isn’t necessarily a bad thing)

Late this summer, the Oxford Dictionary’s online update included the word “selfie,” which it defined as “a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.” Around this time, a flurry of articles traced the rise of the selfie to the social-media boom of the mid-late 2000s, but none mentioned the nascent phenomenon as it existed online prior to the rise of MySpace and Facebook. I happen to know a little bit about this embryonic era of selfie evolution, since, back in the spring of 1999, I began posting a series of self-rendered photos that I dubbed my “Narcissus Gallery.”

Though posting selfies to the World Wide Web may have been novel in 1999, amateur self-portraiture was not. The popular art of taking an arm’s-length photo of one’s own face probably began with the introduction of inexpensive “snapshot” cameras in the early twentieth century, and by the late twentieth century this sort of proto-selfie (typically taken with a point-and-shoot film camera) was a common way to document a life-moment when nobody else was around. In the late 1990s, when I was first embarking on what would become a multi-year vagabonding journey across Asia, Europe, and the Middle East, the selfie was a well-known ritual among backpackers who wanted to document themselves in solitary, far-flung settings.

The irony of pre-digital travel-selfies was that taking a snapshot of your own face by holding out your arm out rarely provided much in the way of visual context. When the picture in question came back from the photo-lab, it tended to be an off-center shot of your own face, with just the slightest hint of the exotic landscape that surrounded you. Hence the joke inherent in my Narcissus Gallery, which featured my sweaty traveler’s visage in places like Egypt, Thailand, Syria, Russia, Laos, and Israel: At a private level I had taken these photos to commemorate moments of personal significance — so sharing them online (to readers who wouldn’t recognize the physical surroundings were it not for the captions) carried a whiff of absurdity.

As it turned out, however, online readers loved the Narcissus Gallery. Of the folks who found my author website through the travel dispatches I was writing for Salon.com at the time, far more of them sent emails expressing interest in my proto-selfies than in my more conventional travel snapshots. Unlike my focused, well-composed shots of Mekong riverboats and Gujarati wedding ceremonies, the ragtag, “I was here!” energy of the Narcissus images inspired readers to relate their own “narcissus” travel moments. Whimsical self-awareness, I came to realize, was not some detached traveler’s gesture — it was intrinsic to the way many people were negotiating the subjective experience of unfamiliar places.

As reader reactions to my Narcissus Gallery suggested, the psychology behind the arm’s-length self-portrait is nothing new. What has changed since 1999 is social-media technology, which has transformed the selfie from a private ritual to public gesture, practiced by celebrities, proliferated by teenagers, and deconstructed by media pundits. Last December, Timemagazine listed “selfie” as one of its “top 10 buzzwords of 2012“; this year, highbrow publications like the New Yorker and the New York Times Sunday Review have weighed in on the phenomenon, and selfie-themed art installations have appeared at venues ranging from London’s Moving Image Contemporary Art Fair to New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

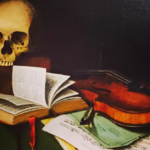

Amid this buzz, the simultaneous criticism and celebration of the selfie trend — is it narcissism or self-expression? — feels like an extension of a much older conversation about the role that images play in the way we make sense of life. When, two generations ago, Susan Sontag wrote how “needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted,” she very well could have been making a prophetic observation about selfies. In her 1977 book On Photography, Sontag noted how the camera has a way of turning people into “tourists of reality,” and she used the rituals of tourism to illustrate how we use cameras to help navigate lived experience. “The very activity of taking pictures is soothing,” she writes, “and assuages general feelings of disorientation that are likely to be exacerbated by travel.”

When Sontag wrote this, travel was one of the few contexts in which an amateur photographer might snap pictures that could find an audience beyond immediate family members. Few people, if any, assembled public slide shows consisting of quotidian life at home or school, but well-curated collections of vacation slides were commonly shown at community libraries, civic clubs, and house parties. By the mid-2000s, however, social media had erased the popular distinction between which life-moments were and were not worthy of public consumption. In the process, it became normal to assemble and project one’s domestic identity for a much broader (and dimly defined) notion of community. Reflexive photo-mania, once a stereotype that defined tourists, had transformed into a ritual of home.

This touristification of everyday life needn’t be thought of as a bad thing. Despite the pejorative implication of the term, tourists are people who are, at some level, trying to create a new narrative for themselves. As self-documentation continues to evolve into a form of self-declaration, snapping a selfie has become a way of illustrating that narrative, even in familiar environments. In a certain sense, this is more than a nod to self-awareness; it’s a method of orienting oneself amid the received noise of twenty-first century life — a way, in other words, of paying attention during the journey.

Rolf Potts is the bestselling author of Vagabonding: An Uncommon Guide to the Art of Long-Term World Travel, which is now available as an audiobook.