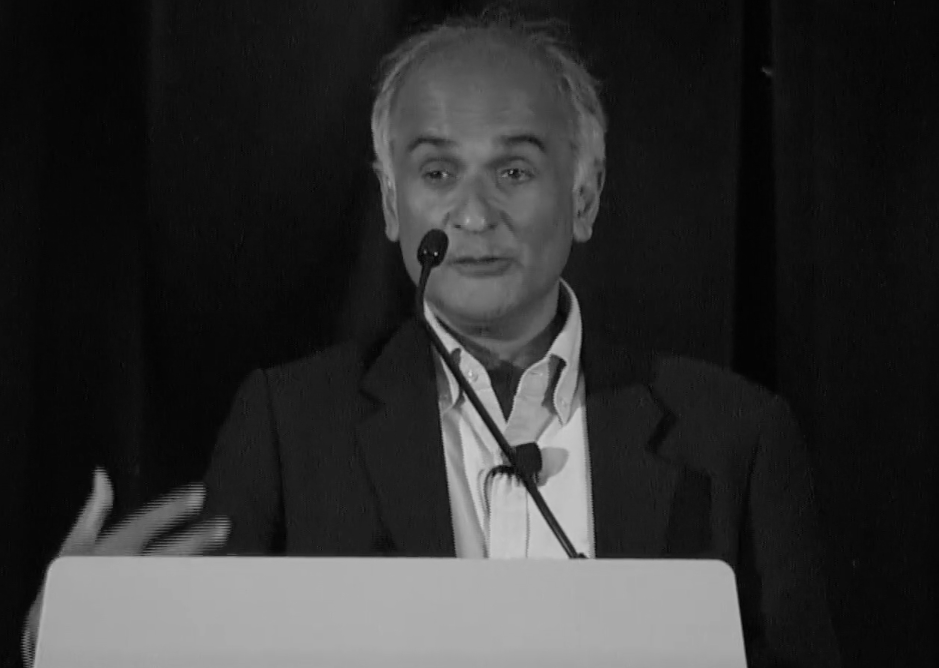

Pico Iyer has published 15 books, on subjects ranging from the Dalai Lama to globalism, from the Cuban Revolution to Islamic mysticism. They include such long-running sellers as Video Night in Kathmandu, The Lady and the Monk, The Global Soul, The Open Road and The Art of Stillness. At the same time he has been writing up to 100 articles a year for Time, The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the Financial Times and more than 250 other periodicals worldwide. The following quotes come from “Why We Travel,” his TravelCon keynote speech, delivered on April 29, 2022.

1) One can’t truly experience the world second-hand

One of the great beauties of the modern moment is that all the world has come to our doorstep. And yet I feel that it’s everything essential about a place that you can’t get at second hand. It’s the smell of frankincense when you step into your hotel lobby in Oman. It’s the wind in your hair when you’re sitting on some treeless hill in Iceland and looking out over this great volcanic waste. …I sometimes think that one reason that food has become so essential to people’s travels nowadays is you can’t taste sushi online yet. You have to go to Jiro’s little, uh, bar in the subway station in Tokyo to experience it.

2) Intangibles are what makes the travel experience special

I’ll never forget five years ago, I was at the TED conference in Vancouver and I stepped into this state-of-the-art virtual reality booth. I could see the vibrant greens of the Amazon rainforest. I could hear the cooing of these tropical birds. I could almost feel the precipitation on my face. But when I stepped out of it again, I thought it’s everything essential about the experience I couldn’t get there. It’s the silences, the sense of surprise the intangibles. It’s a sweat on my brow that would’ve come if I’d really earned that experience. Even now it’s really hard to fall in love at second hand.

3) Travel reminds us how much we don’t know about the world

I think in these days, when so much reality is virtual, so much intelligence is artificial, and so much news is fake. it’s more important than ever really to go out into the world and to be reminded of how much we don’t know, and how much doesn’t fit into our explanations. I worry that in the age of streaming news, what we really lose out on is human complexity. In the age of the iPhone, we forget that all the images in the world never add up to real life, and in the age of the small screen is really hard to catch the larger picture.

4) Travel is less about seeing sites than seeing in a new way

Thoreau knew that travel isn’t about seeing the sites. It’s about getting a new way of seeing. As soon as you have that new way of seeing, even the old places look different. Travel wasn’t really about movement. It’s about being moved.

5) Travel allows us to see life that goes beyond news headlines

Sometimes we know least of all about the countries we hear most, about like North Korea or Iran or Cuba. We hear quite a lot about their leaders, or their battered economies, maybe their nuclear policies, but we have a painfully negligent sense of daily life and just regular folks.

6) The world is so much richer than our ideas of it

I’ve been traveling the world constantly for 48 years now. And I think you can really only conclude it’s a small, small world if you’re in Disneyland. To me, the distances and the differences between us are greater than ever before, partly because of the illusion of smallness and closeness. And that’s what makes the world so inexorably fascinating. And that’s why the world is always so much richer than our ideas of it. And in fact, the criscrossing of cultures the last 40 years has thrown up a whole new dimension of exoticism.

7) The familiar is a lens through which to see the exotic

It sounds facetious, but it’s really true that in the late 1980s, when I was in Beijing, I felt I could see more about China by going to the new KFC, following one corner of China than square than by going to the Forbidden City in another corner of the square. Cause I didn’t really know enough about China to understand the Forbidden City.

8) Negatives can reveal as much about a place as positives

I have three rules for myself when I’m writing about a place. My first is never to try to be only positive about a place. Because if I am, I feel that suggests that I’m either too lazy really to look at it, or too dishonest to say what I truly think about it. For me, places are like people, and truly they’re like my friends. When I’m describing my friends, what really distinguishes almost all of them is their eccentricities and their foibles. That’s what makes them lovable. If I were only to say glowing things about a friend, I think I would almost be an insult to reduce him to a kind of stereotype.

9) Travel at its best is an exercise in curiosity

My second rule for myself is always to try to remember that travel remains an exercise in curiosity, not in consumerism. If you are a master chef or if you really understand food, then I think it’s makes a lot of sense to spend three hours in an elaborate meal in Paris. But when I’m in Paris, I want to wander in the streets, smell everything, see everything, look through the windows, eavesdrop on people all around me. I want to spend those three hours consuming the whole culture rather than just a single meal.

10) The best way to get to know a place is to walk in it

I think the first thing in a new place is just walk and walk and walk everywhere with my little notebook, which is pretty much the only thing I have. It’s like meeting a fascinating stranger and you want to hear her life story. So just letting the place speak to me, listening to it, taking notes on everything, going down every last little street, uh, and every, maybe two and a half, three hours I’ll stop and have a cup of tea and process it. Then when I go back to my hotel at the end of the day, I’ll write it up in full paragraphs because that’s how you catch the emotion. If you’re just making scrap little short notes, that’s not catching the feeling and I won’t be rich enough ever to go back to that place or to experience that first day again. If I go to a place where it’s not possible to walk, I will get on a bus and get off at the last stop or take a subway or whatever. I do that for the first 48 hours, because after about three days, I find ideas begin to form explanations. And at that point I only see everything that confirms them. I only see everything in the light of my expectations. Those first 48 hours are very important. I still keep, as I say, writing, writing everything up while I’m in the site. I will come back from a two week trip with maybe 40 or 50, a hundred pages of notes. And then ideally I will wait for two weeks or two months and then ask myself a variation on the first question, what moved me most? What surprised me most and how can I live differently in the light of what I experienced? How can I bring Tibet or Havana or Jerusalem into my life in Japan or New York City? Uh, and sometimes there’s a tight deadline and I have to write it very quickly, but I try to let memory do the, the sifting. I often will leave all those notes on one side of the room and just imagine I met a friend and she said to me, what was so amazing about Iceland? I’d start to talk to her. And that’s probably how I should start my story. And of course the beauty of the writing process is you get surprised by it and saying this in the walking process.