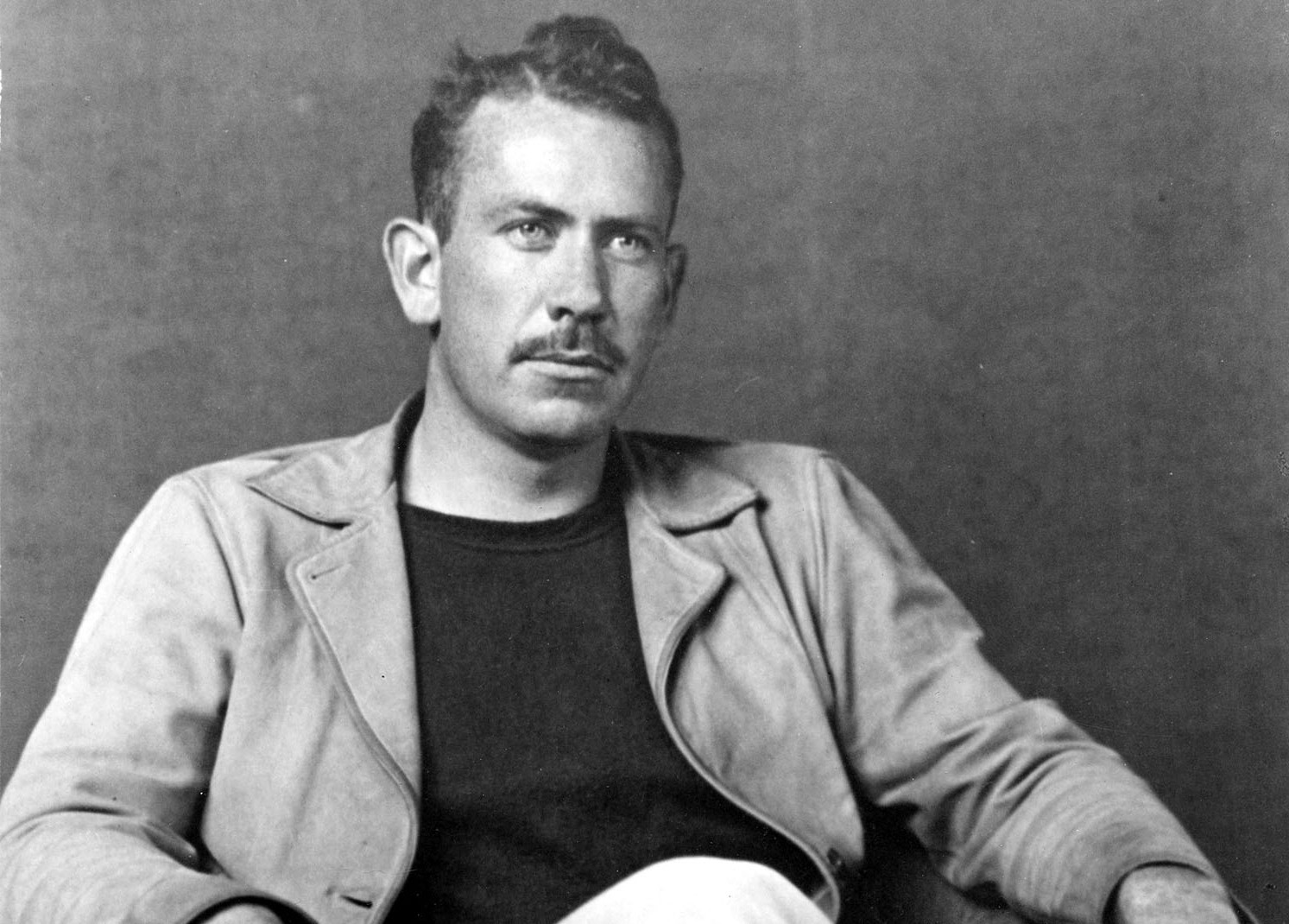

Cannery Row has been one of my favorite books ever since I first read it as a teenager. John Steinbeck’s gentle depiction of Depression-era ne’er-do-wells in Monterey, California doesn’t typically appear on lists of great American novels (and Steinbeck himself is better known for works like The Grapes of Wrath, East of Eden, and Of Mice and Men), but every few years I find myself returning to the book, its characters, and its understated evocation of joy.

It’s hard to pin down a plot in Cannery Row, which is part of the charm of reading it. The book plays out in a series of vignettes that — when boiled down to their essence — involve a group of vagrants trying (and failing, and then trying again) to throw a party for a kind-hearted, quietly charismatic marine biologist named Doc.

Doc, who is modeled on Steinbeck’s real-life friend Ed Ricketts, has eclectic intellectual interests, an understated sense for the absurd, and no shortage of friends. But his charm is offset by a deep sense of melancholy that gives the book’s climactic house-party a wistful, introspective edge.

This melancholy often plays out in Doc’s choice of music, and I didn’t pay much attention to the specific textures of this music until I reread the book (for probably the sixth or seventh time) a couple years ago and cross-referenced songs and composers online. In this way I was able to enjoy an already beloved book on an even deeper level, and, in the interest of offering other readers the same experience, I’ve put together a guide to Doc’s music here.

Monteverdi’s Hor ch’ el Ciel e la Terra

Doc doesn’t actually play this madrigal, which is based on a sonnet by Petrarch (and translates, roughly, to “At the Time of Heaven and Earth”). This is because his record player was destroyed when Mack — who Steinbeck characterizes as “the elder, leader, mentor…of a little group of men who had in common no families, no money, and no ambitions” — threw a disastrous party at Doc’s house when Doc was not there.

So, instead, the music plays out in Doc’s mind:

Mack sat down in a chair and looked at him. Mack’s eyes were wide and full of pain. He didn’t even wipe away the blood that flowed down his chin. In Doc’s head the mono-tonal opening of Monteverdi’s Hor ch’ el Ciel e la Terra began to form, the infinitely sad and resigned mourning of Petrarch for Laura. Doc saw Mack’s broken mouth through the music, the music that was in his head and in the air. Mack sat perfectly still, almost as though he could hear the music too.

Ravel’s Pavane for Dead Princess

Later in the book, when Doc has clued in to the fact that his friends plan to throw him another party, he hides his breakables, enjoys a drink, and plays some Ravel before guests arrive:

Over at the laboratory, Doc had a little whiskey after his beer. He was feeling a little mellow. It seemed a nice thing to him that they would give him a party. He played the Pavane to a Dead Princess and felt sentimental and a little sad.

Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe

Reveling in the mood of the somber processional, Doc plays a choreographic symphony by the composer:

And because of his feeling he went on with Daphnis and Chloe. There was a passage in it that reminded him of something else. The observers in Athens before Marathon reported seeing a great line of dust crossing the Plain, and they heard the clash of arms and they heard the Eleusinian Chant. There was part of the music that reminded him of that picture.

Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata

Once he’s finished listening to Ravel, Doc considers lightening his mood with some Bach, but instead chooses to double-down with Beethoven’s haunting piano composition:

When it was done he got another whiskey and he debated in his mind about the Brandenburg. That would snap him out of the sweet and sickly mood he was getting into. But what was wrong with the sweet and sickly mood? It was rather pleasant. …He poured a whiskey and drank it. And he compromised with the Moonlight Sonata . He could see the neon light of La Ida blinking on and off. And then the street light in front of the Bear Flag came on.

Monteverdi’s Ardo

Just before the party guests begin to arrive at Doc’s place, Steinbeck interjects a mock-philosophical observation that the science of parties is somewhat imperfect. “It is, however, generally understood that a party has a pathology, that it is a kind of an individual and that it is likely to be a very perverse individual,” he adds. “And it is also generally understood that a party hardly ever goes the way it is planned or intended.”

In Doc’s case, the party starts on a note of awkwardness as Mack and the boys arrive to present him with gifts. Things relax as more guests arrive, however, and eventually Mack plays some Benny Goodman records. Responding to the music, people begin to dance, eat, and get into the occasional fistfight. Dora Flood, the stately orange-haired bordello madame, eventually senses Doc’s mood and requests a music change:

Now the food set the party into a kind of rich digestive sadness. The whiskey was gone and Doc brought out the gallons of wine. Dora, sitting enthroned, said, “Doc, play some of that nice music. I get Christ awful sick of that juke box over home.” Then Doc played Ardo and the Amor from an album of Monteverdi. And the guests sat quietly and their eyes were inward. Dora breathed beauty. Two newcomers crept up the stairs and entered quietly. Doc was feeling a golden pleasant sadness. The guests were silent when the music stopped.

Monteverdi’s Amor

With the mood of the party shifted to melancholy, Doc reads from “Black Marigolds,” a 50-stanza 11th century Sanskrit love poem that tells the story of Chauras, a Brahman poet who is sentenced to death for his illicit love-affair with Vidya, the daughter of the king.

By the time Doc is done reading “a little world sadness” slips over the guests:

Phyllis Mae was openly weeping when he stopped and Dora herself dabbed at her eyes. Hazel was so taken by the sound of the words that he had not listened to their meaning. …They filled the wine glasses and became quiet. The party was slipping away in sweet sadness, Eddie went out in the office and did a little tap dance and came back and sat down again. The party was about to recline and go to sleep when there was a tramp of feet on the stairs. A great voice shouted, “Where’s the girls?”

Gregorian Chant: Pater Noster

The party at Doc’s ultimately turns into a barnburner. “You could hear the roar of the party from end to end of Cannery Row,” Steinbeck writes. “The party had all the best qualities of a riot and a night on the barricades.”

The following day, as Doc cleans up, his wistful melancholy returns:

Doc cleared a place on the table for the clean glasses as he washed them. Then he unlocked the door of the back room and brought out one of his albums of Gregorian music and he put a Pater Noster and Agnus Dei on the turntable and started it going. The angelic, disembodied voices filled the laboratory. They were incredibly pure and sweet. Doc worked carefully washing the glasses so that they would not dash together and spoil the music. The boys’ voices carried the melody up and down, simply but with the richness that is in no other singing.

Gregorian Chant: Agnus Dei

As he listens to the Gregorian music, Doc spots the book of Sanskrit poetry sitting on the floor, and Cannery Row ends with the wiry biologist reading aloud from the final stanzas of “Black Marigolds”:

Even now

I know that I have savored the hot taste of life

Lifting green cups and gold at the great feast.

Just for a small and a forgotten time

I have had full in my eyes from off my girl

The whitest pouring of eternal light —

Note: I don’t host a “comments” section, but I’m happy to hear your thoughts via my Contact page.