I couldn’t see into the sleeping room, but the hotel’s owner, who appeared to be tipsy on his own liquor, told me that Mursi tribesmen and their families paid the equivalent of 20 cents per person to sleep on the packed-dirt floor. I was sitting in what the owner called the “drinking room,” a smoky, lamp-lit chamber with grimy turquoise walls, a sagging tile ceiling, and tattered posters of Jesus and Mary tacked up behind the bar. The Mursi men, who were required to check their fighting staves at the door, sat on low wooden benches, sipping at small glasses filled with a cloudy liquor called araki. Their wives, whose ceremonially severed lower lips sagged around their chins as they nursed babies in the dim light, sat on the floor along the wall. Everyone stared at a table in the front of the room, where a small television flickered with black-and-white images of light-skinned Ethiopian entertainers cavorting to Bollywood-esque pop songs. The air was thick with the smell of fermented sorghum and hand-cured goat leather.

The Mursi had arrived on foot, walking for as much as one week from the isolated hill country of southwest Ethiopia to the only metropolis they knew—Jinka, a market town of 22,000 people. The hotel, which sat at the back of a dirt alley and had no sign, catered to their tastes. Araki was the only drink on offer, and the owner sloshed it into a plastic bottle from an unwieldy jerrycan before moving around the room to refill clients’ glasses for ten cents a shot. The drink, he told me, had been distilled several valleys away, in the town of Konso; it was made from sorghum and barley, and sold mainly to country folk and tribal people like the Mursi, who couldn’t afford commercial spirits. The araki smelled rich and rotten and organic when I brought it to my nose. It burned going down, filling my sinuses with a potent, sileage-like aroma; my eyes watered, and I choked out a cough. The Mursi men next to me tittered as the owner brought me a glass of cola to help wash the liquor down.

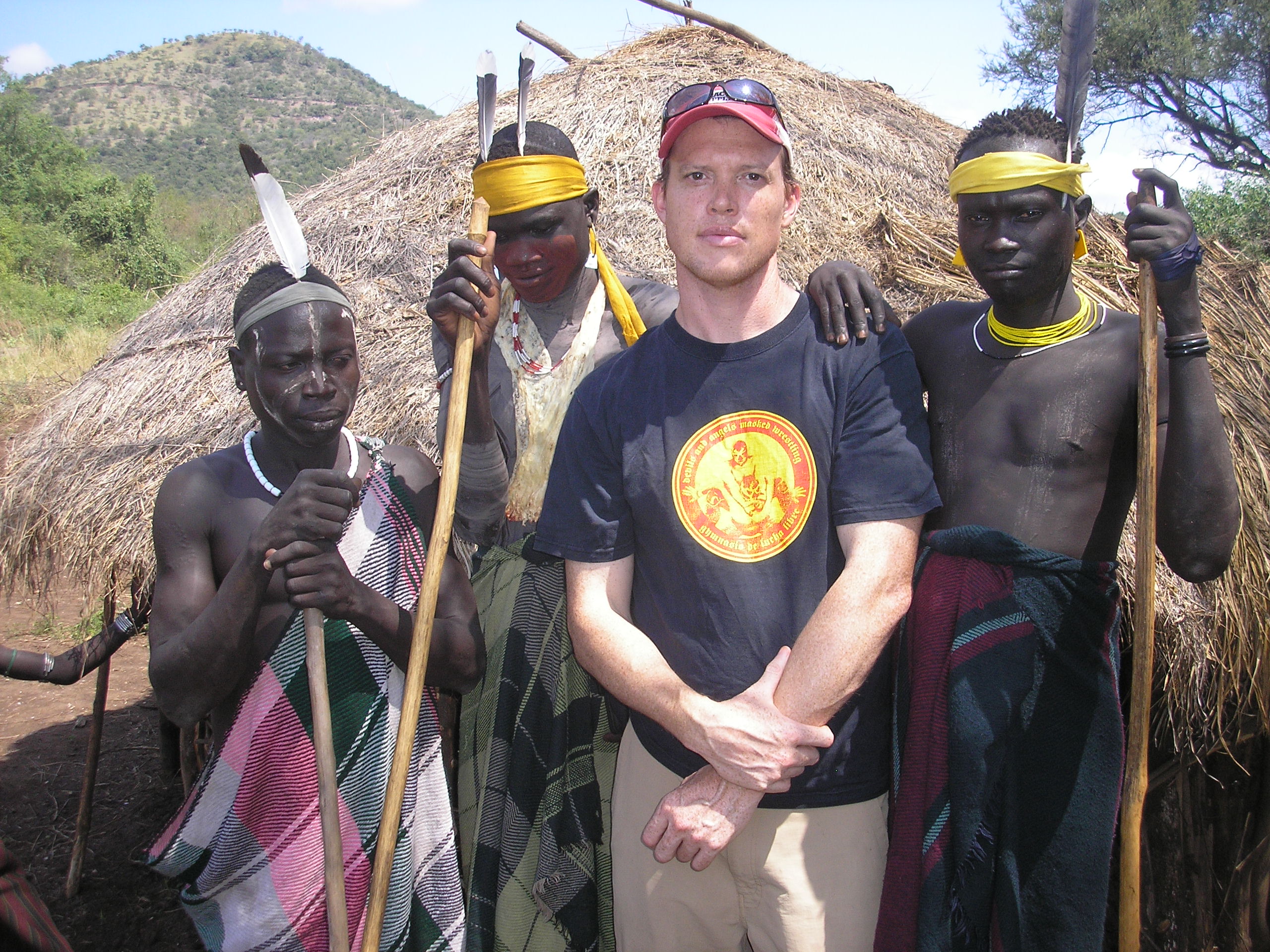

Earlier that day I’d seen Mursi tribesmen in a markedly different setting, at a village three hours by jeep south of Jinka. There, the men had brandished AK-47 rifles outside of grass-walled huts, wearing headdresses studded with feathers, rebar rings, and warthog tusks. The women had balanced beaded baskets atop their heads, their faces painted a chalky white, their lower lips stretched taut by ocher-painted clay plates the size of coffee saucers. This colorful display was purely for the benefit of the half-dozen tourists, myself included, who’d come to take photos of Ethiopia’s most striking-looking tribespeople. The Mursi had bargained fiercely for the right to be photographed; prices had started at just over $1 per snapshot.

By contrast, the Mursi in the dark little Jinka hotel bar wore simple tartan shawls and paid me little mind as they stared at the television and chatted softly amongst themselves. The following morning they would take their butter and honey to the market and trade it for cash and manufactured goods before beginning the long walk home. Like me, they were travelers in Jinka, sipping their araki slowly, as if to savor the novelty of the moment.