By Rolf Potts

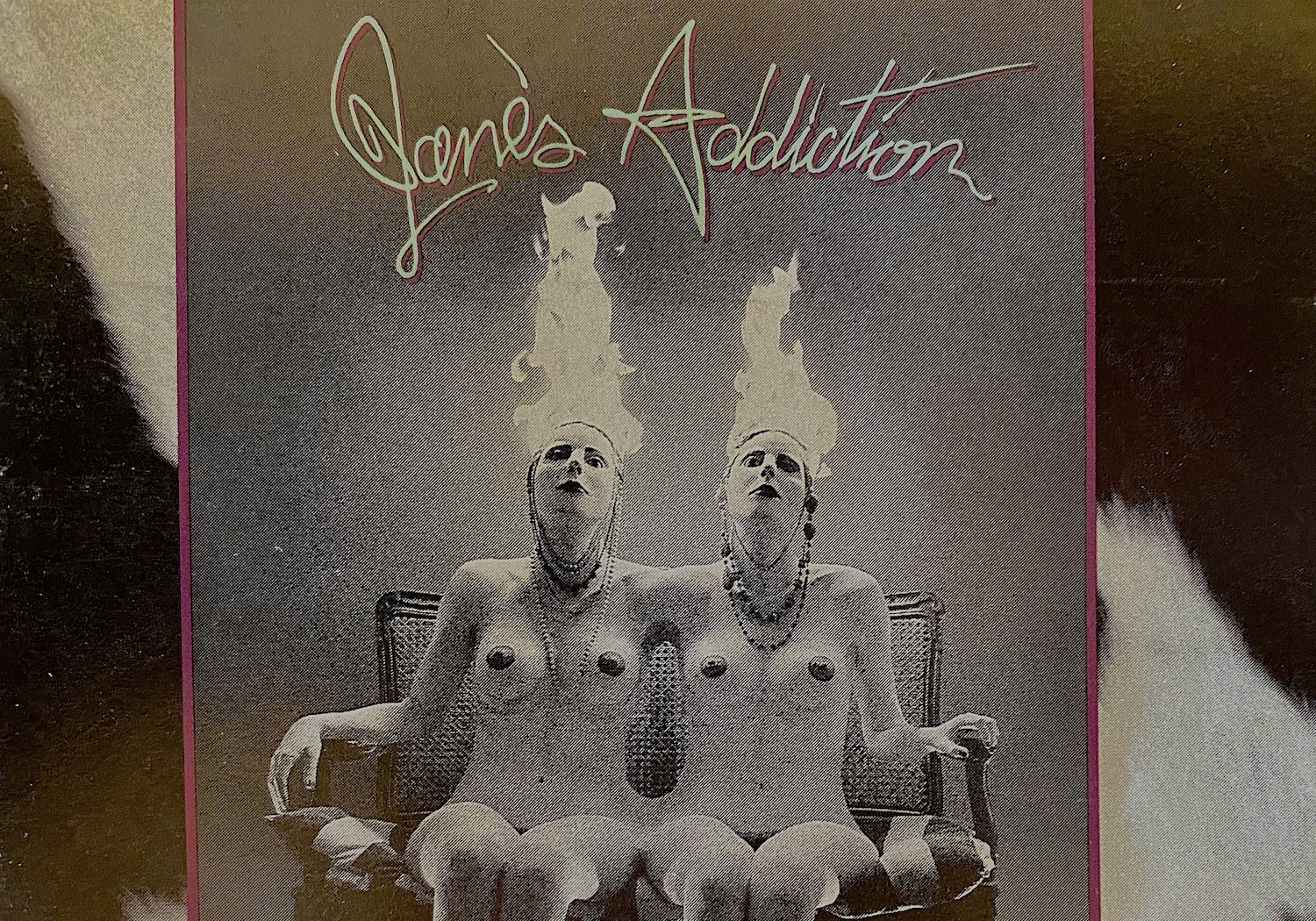

Note: This is the expanded version of an essay that appeared in the 2019 Bloomsbury anthology The 33 1/3 B-sides: Authors on Beloved and Underrated Albums.”

I was riding in the passenger seat of Hadley’s red Honda CRX when I heard Jane’s Addiction’s Nothing’s Shocking for the first time. It must have been a Saturday, since that’s the only day of the week we ever had off from our summer jobs at Eagle Lake Camp, where we were tasked with taking adolescents into the Rocky Mountain backcountry and telling them about Jesus.

Hadley was from California. She was blonde, leggy, doggedly cheerful, and a tad clumsy when she shouldered her backpack and led campers into the Colorado wilderness. She had a goofball sense of humor, a jolly inability to show up on time for staff meetings, and a tendency to drive too fast on the pine-hemmed curves of Rampart Range Road, the gravel-track that linked our summer camp to Woodland Park, the nearest town, 35 minutes away. Hadley kept the CRX sunroof open as she drove, and the car swirled with the summery chill of mountain air and the vanilla smell of ponderosa. I had recently graduated from high school in Kansas, and my two months in Colorado amounted to the longest I’d never spent away from home. I was in love with Hadley in the passive, uncomplicated way all 18-year-old boys fall in love with 21-year-old women who pay attention to them.

Hadley liked to talk when she was driving – usually about people she knew or places she wanted to visit, but never about Jesus, which I found a relief, since our summer-camp coworkers had a way of dropping Jesus into casual conversations in a way that made me nervous. When Hadley tired of talking she would snatch one of the dozen or so unsheathed cassette tapes that slid around on the CRX’s floorboards and blast tunes. Apart from U2, which all young Christians were obligated to enjoy (or at least acknowledge) in 1989, I didn’t recognize any of Hadley’s music. I had suggested we play The Joshua Tree at the outset of our drive to Woodland Park, but – halfway through Bono’s emotive rendering of “Running to Stand Still” – Hadley frowned at the sunlight slanting through the pine trees all around us, as if something wasn’t quite right. Ejecting U2, she brandished a gray Maxell dub-cassette and slid it into the tape deck. “Jane’s Addiction,” she announced, cranking the volume as a slurry, roiling bass groove shook the car.

To fully appreciate the way I felt in the minutes that followed, it’s important to apprehend how young men from the provinces experienced music in 1989. Possessing neither the sophistication nor the disposable income to learn about music from underground rock magazines or indie record stores, most of what I knew about popular music came from T-95, Wichita’s album-oriented rock station, which mixed flavor-of-the-month hair-metal songs with hard-rock standards by the likes of AC/DC and Led Zeppelin. Dubbed cassettes of appealingly profane acts like the Violent Femmes and N.W.A. had made the rounds at my high school, and I’d pumped myself up for senior-season track meets by listening to Metallica’s Master of Puppets – but for the most part I wasn’t familiar with edgy or genre-defying music. The graduation parties I’d attended that spring had featured the hits of the day – a mix of Poison and Janet Jackson, Cinderella and Milli Vanilli, Skid Row and Richard Marx.

By contrast, “Up the Beach,” the ethereal, muscular, faintly psychedelic anthem that swelled over the bass-line as Hadley’s car sped through the pines, was like nothing I’d ever heard before. When the singer’s voice shrieked up over the opening groove, it didn’t form words so much as weave its way into the cascading guitar notes, swirling out and echoing back in on itself. The effect was magical, incoherent, mesmerizing: Time, it felt, was decelerating, spooling out in slow motion. The song’s only discernible lyric was “home,” which the singer intoned with a plaintive, almost tender sense of urgency as the song’s final chords rang out, pulsed, faded away.

In the span of just three minutes, “Up the Beach” had filled me with a haunted sense of longing. I might have asked Hadley to rewind the tape and play it again had we not at that moment been speeding toward my favorite stretch of Rampart Range Road – a spectacular, two-mile span of grassy, treeless plateau with the elegant hulk of Pikes Peak dominating the westward horizon. The echoing silence after “Up the Beach” melded into a new texture – the shiny, almost classical-sounding chime of guitar threaded with a falsetto coo that built up, stretched out, then softened as Hadley drove us up from the trees into the sun-dazzled alpine meadow. Glancing over at me with a sideways grin, she shouted: “One, two! ” and, before I could figure out what she was getting at, a banshee voice screamed “three, fooouuurr!” and the little world inside the car exploded into a thunderous clamor, a hammering swell of guitar, bass, and drums, a sound too powerful and thrilling for me to ever put into words. “Wish I was ocean size,” the vocalist howled, sounding like there was a thousand of him calling to me from a thousand miles away, “no one moves you, man, no one tries!”

As Hadley’s CRX crested the grassy rise and Pike’s Peak hove into view above the rocky sprawl of Colorado’s Front Range, I felt like I was gazing out at a whole new universe.

The fact that I can’t help but use the before/after language of transformation in recounting my first encounter with Jane’s Addiction’s Nothing’s Shocking is inseparable from the place where Hadley and I had been working that summer. Eagle Lake Camp was affiliated with an evangelical Christian organization, one of several Colorado Springs-based outreach ministries that had set up summer recreation programs in the mountain-fringed national forest northwest of the city. In the evangelical world, religious faith is not something you inherit from your family or absorb from the culture around you – it’s an active, life-changing choice on the part of a spirit-filled individual. The story of that choice, which evangelical Christians are more or less obligated to share with everyone, is called a “personal testimony.” In the summer of 1989 I did not have a personal testimony – or, at the very least, I didn’t have a very good one – and this was a source of consternation for my employers.

At this point I should probably clarify that while my ecstatic introduction to Jane’s Addiction that day in Colorado most certainly changed my life, it didn’t much change my relationship to my faith, or the core task of my job at Eagle Lake Camp. In the secular world, there is an entire literary subgenre of post-evangelical confessional essays, many of them set at holy-roller summer camps not dissimilar to the one I worked at in 1989. These memoirs tend to involve some combination of blind belief, hypocritical adult role-models, intolerant interpretations of scripture, right-wing fanaticism, sexual confusion, isolation from mainstream culture, a moral betrayal of some sort, and – ultimately – a reverse-conversion experience wherein the narrator escapes the repressive confines of evangelicalism and embraces a more enlightened spiritual understanding. This is not going to be one of those essays, in part because my Eagle Lake coworkers were decent people – but mainly because I’d never considered myself evangelical.

I’d grown up Lutheran – a traditional Protestant denomination that some of my summer-camp coworkers had derided, along with other mainline sects like Presbyterians and Methodists, for being “spiritually dead.” By this I think they were taking issue with the stultifying rituals (nineteenth-century organ hymns, liturgically prescribed sermon themes, group recitation of medieval-era creeds) that took place in old-school churches like the one I’d attended as a kid. I’ll admit that I did endure countless youthful Sundays bored silly by the grinding predictability of Lutheran worship. But I also came to respect the people I knew there – the bulk of them working-class parishioners with German or Scandinavian surnames, folks who did their best to abide by the edicts of the gospel, went out of their way to help each other out in times of need, and had little taste for performative piety. Pastor Meyer, the cerebral, grey-bearded ex-missionary who taught my adolescent confirmation classes, took pains to ground us in the concrete, nuanced teachings of Jesus rather than hellfire and brimstone abstractions.

My first immersive encounter with evangelical Christianity came at Eagle Lake itself, which I began to attend at age 11 at the encouragement of a friend of my parents. I fell in love with the place immediately, in part because of its gorgeous mountain setting and exotic diversions like rock climbing, but also because it made faith seem fun. Worship services featured guitar sing-a-longs, relatable sermons, and hugging. Elementary-aged kids slept in teepees named for Indian tribes and competed in a camp-wide Olympics that mixed sports with Bible-memorization; junior high kids took weeklong backpacking trips in the national forest, where they learned how to rappel, camped out in the mountains overlooking Colorado Springs, and sang praise songs around the campfire. Counselors prefaced most every activity – meals, sporting events, evening lectures – with rambling, extemporaneous prayers. Private prayer was also encouraged, as a kind of inner dialogue with Jesus, who, we were told, had a personal interest in how we lived our lives (right down to our performance in camp-Olympics volleyball games). Devotions touched on the parables and sermons of Jesus, but counselors and campers alike seemed more interested in the science-fiction bluster of Revelations. End Times were speculated upon at length, as were the physical conditions of heaven and hell.

Of all the idiosyncrasies that set my evangelical summer camp apart from the Lutheran church back home, however, the most prominent was the seeming compulsion to talk about Jesus at every possible opportunity. No ritual of traditional devotion – neither contemplation nor self-abnegation nor charity – was quite so important as what the counselors called being “on fire for the Lord.” This, apparently, meant enthusing about “the work God is doing” in one’s own life, asking others about their “walk with Lord” (often abbreviated to “How’s your walk?”), and ministering to folks about the joys of having Jesus Christ as a “personal Lord and Savior.” This last task, which evangelicals referred to as “witnessing,” was one of the institutional missions of the camp – though few, if any, heathen families sent their kids there. This meant the counselors spent most of their time urging Christian kids to become more demonstrably Christian.

Within this culture of hyper-verbalized faith, sharing one’s personal testimony was seen as both a witnessing tool and a demonstration that one’s devotion to God was authentic. A testimony couldn’t simply recount being born into church-going family and holding steadfast, since that offered the listener no narrative – no before and after, no cause and effect, no lost and found. The most warmly received testimonies, I quickly learned, pinpointed (a) a specific kind of sin, (b) a tantalizing suggestion of just how damaging that sin was, (c) a key moment of personal crisis that resulted from the sin, (d) an encounter with a person or place (often Eagle Lake Camp) that helped the narrator appreciate the redemptive love of Jesus, and (e) a celebration of the humble joys and challenges of a faith-filled life. Invariably, the inciting sin would be something lurid and adolescent, like drunkenness or lust; few testimonies focused on the more abiding sins – materialism, gossip, self-absorption – that tended to vex real evangelical communities.

When I landed a job at Eagle Lake in the summer of 1989, the camp director informed us that all staff members were required to share their testimony as an inspirational example to the campers. Though it wasn’t stated explicitly, it was implied that, if possible, our testimonies should highlight the kinds of sins our pubescent clients might be struggling with. By the letter of the staff honor-code we could literally get fired for drinking, thievery, or heavy petting – yet we were encouraged to confess to these same vices so long as they symbolized our pre-redeemed past.

The problem for me was that, at age 18, my vices had yet to advance beyond a few wine coolers and some mid-to-light petting with my high school girlfriend. Moreover, I didn’t feel like I had a pre-redeemed past: I was born saved, to a family I loved and respected, in a Lutheran church which (frumpy and understated and imperfect as it was) left me feeling spiritually grounded in a way Eagle Lake didn’t. I adored Eagle Lake, with its mountains and its starry nights and its chatty, charming born-again exuberance. But it felt wrong to embellish some corny, before/after evangelical mini-drama just to appease the people who worked there. When I tried to explain my earnest lack of conversion-narrative to the camp director, he seemed chagrined. One’s relationship to knowing Jesus should never be passive, he told me. The very act of sharing it should inspire others. The things that we truly love, he added – the things we feel in our souls and think about when nobody else is around – invariably find expression through enthusiasm.

As it happened, I did develop an irrepressible, deep-soul enthusiasm that summer; it just wasn’t for evangelical Christianity. It was for Jane’s Addiction’s Nothing’s Shocking.

In retrospect, I think Hadley was a bit startled by my fixation with Jane’s Addiction after our heady Saturday-morning drive in her Honda CRX. I’ve come to realize that Hadley has, in my memories, served as a kind of Manic Pixie Dream Girl – a stock narrative character (often seen in movies) whose eccentric tastes and quirky enthusiasm for life ultimately serves to shepherd the young male protagonist on a journey of self-discovery. Hadley was indeed quirky and ebullient, but her decision to play Nothing’s Shocking instead of The Joshua Tree that day hadn’t been a symbolically charged ploy to change my life. In real-time, with the sun filtering through the pines on Rampart Range Road, I’d reckon she’d simply felt the blissed-up urge to hear it. In the days and weeks after our drive I grilled her for more information about Jane’s Addiction, but she didn’t seem to know a lot about the band. She was pretty sure they’d emerged from the post-punk glam scene in Los Angeles, and that the bewitchingly powerful sound I’d found so intoxicating was the result of them blending gothic rock with heavy metal. I recall nodding along as she said this, though the only phrases that had any meaning for me at the time were “heavy metal” and “Los Angeles.”

Unlike Hadley, I wasn’t a full-on counselor at Eagle Lake Camp. As the youngest member of the staff I’d been given the apprentice-level job of trip outfitter, which meant I spent most of my time repairing camping gear and preparing food for the other counselors to use when they took kids into the backcountry. I liked the job, and I was good at it. Each 12-day session culminated with a banquet in a meadow two miles by trail from camp, and I prided myself on being able to carry in more than 100 pounds of marinated chicken and iron cookware in one haul. Once, when I realized Hadley’s adolescent cohort had forgotten to pack the cheese for their quesadillas, I brandished a topographical map and jogged five miles into the forest to deliver it in time for dinner (“without cheese they’re just ‘dillas,” I’d quipped on arrival). Back at camp I’d been assigned a bunk in a six-man platform tent, but I slept most nights outside in my nylon hammock, under the pines, under the stars.

The trip outfitter’s office had a battered Panasonic boom box, and the fact that I mostly worked alone meant that I didn’t have to endure the syrupy Christian praise-pop favored by most of my coworkers. After my first flirtation with Jane’s Addiction I’d begged the dub-cassette off Hadley, and I wound up listening to Nothing’s Shocking as many as three times a day for the rest of the summer. The tape’s B-side featured the new debut album by the Stone Roses, an English band whose songs proved consistently catchy, but for the most part I just rewound the tape and listened to Jane’s Addiction again (to this day I can’t hear a Stone Roses song without thinking of Nothing’s Shocking). My affinity for “Up the Beach” and “Ocean Size” – the opening tracks that had so beguiled me that day up on Rampart Range Road – was so strong that sometimes I’d stop the tape when the final strains of “Ocean Size” faded, rewind it, and listen to them both again.

My relationship to all of the music on Nothing’s Shocking, as it played out on the boom box each day, was very much constrained by the pre-internet era. As I listened to the songs on that gray plastic dub-cassette I had no idea who the members of Jane’s Addiction were, what they looked like, or even the names of the songs (Hadley had, as it happened, misplaced the cassette-case J-card that bore the penciled-in titles). The first few times I listened to the album all the way through I was drawn to the heavier tunes, particularly the stomping fuzz-riffs of what I later learned was called “Mountain Song.” The album’s closing track, “Pig’s in Zen,” was even heavier and edgier – unhinged and menacing and uncomfortably electrifying (it also culminated in a demented spoken-word pre-coda that included swearwords, which meant I rarely listened to it all the way through for fear some earnest Christian might walk in and overhear it).

The more I listened to Nothing’s Shocking, however, the more I began to appreciate its less-bombastic songs – the funk-core cacophony of “Standing in the Shower, Thinking,” for example, and the grooved-out noise-creep of “Ted, Just Admit It.” The punk-riff lyrics on “Had a Dad” bewailed the seeming absence of God, yet I found it oddly hopeful (no doubt because I misheard “He’s not there at all” as “He’s not dead at all”). “Jane Says,” a sweet, sad, steel-drum-driven pop number, told the story of the band’s drug-addicted namesake through a progression of lyrical telling-details; it was catchy enough to sing along to, and felt ready for rotation on American rock radio (unbeknownst to me, this had already happened). Over time, however, I came to most anticipate the middle of Nothing’s Shocking, when the thunder of the album’s early songs eased into the psychedelic euphoria of “Summertime Rolls.” Anchored by a sleepy, bouncing bass-line, its lyrics recount a sun-blissed day spent in the company of a loopy, faintly clumsy girlfriend. At the time it made me think of Hadley; now it just reminds of being young and alive in the summer of 1989.

Despite the intensity of my Jane’s Addiction obsession that summer, my Eagle Lake co-workers were scarcely aware of it. Ask them what they remember of me, and they might recall my first 5.9-grade lead-climb on the red sandstone spires of Garden of the Gods; they might recall me tentatively sampling espresso for the first time at a café in downtown Colorado Springs; they might recall me exuding over my paperback copy of Kurt Vonnegut’s Welcome to the Monkey House, and trying to write short stories in the same vein. That summer I used a map and compass with more skill than I had before or have since; I was kinder and more generous (or at least less cynical) toward troubled people than I am now; and, somehow, my fashion-repertoire came to include a maroon surplus-store military beret, which I donned unselfconsciously for most of the following year. But as the summer wore on I hid the intensity of my daily Nothing’s Shocking ritual even from Hadley. In retrospect I think she would have been amused by my compulsion to play her tape over and over in the trip outfitter’s office; at the time I was afraid she’d think I’d was some naïve yokel who took her music way too seriously.

Mostly, of course, my secrecy stemmed from with the religious atmosphere of the camp, with its evangelical insistence on outwardly demonstrative faith. When the truest expression of belief is determined by how much you talk about God in social settings, the other things that excite you have a way of being mistaken for idolatry. As it happened, Jane’s Addiction had indeed found a way into my soul, just not the part of my soul that plumbed the divine; it had occupied that raw, 18-year-old part of my being that was hungry for new music, new experiences, new ideas. It spoke to an inchoate part of me that wanted to be different, to pay closer attention to what I might have been missing, to commune with as-yet-unseen versions of myself. Nothing’s Shocking hadn’t moved me because it filled me with numinous purpose; it had moved me because it filled me with an exhilarated, inarticulate feeling of possibility – a sense that the world was wider and wilder than I had previously assumed.

Two years after my first encounter with Nothing’s Shocking I saw Jane’s Addiction live in concert for the first time. I was back home in Kansas that summer, working the graveyard shift at a supermarket in Wichita and saving up money for my junior year of college. I took a day off work and drove three hours to Kansas City’s Sandstone Amphitheater, where I proffered my $20 ticket and settled in for a sweltering daylong show that also featured acts like Siouxsie and the Banshees, Nine Inch Nails, Ice-T, Rollins Band, and the Butthole Surfers. I’ve since come to refer to that summer – the summer of 1991 – as “the year I cut off my mullet and went to Lollapalooza.”

Since that time I’ve come to realize that the simplistic before/after conceit of “personal testimony” storytelling isn’t unique to evangelical Christianity: It’s how we all tend to make sense of past events, whatever their spiritual import. In the popular imagination, 1991 has come to be remembered as a turning-point year in that fin de siècle moment before the Internet upended the way we consume culture. Prior to 1991, the story goes, bloated pop and hair-metal acts ruled the airwaves, before the meteoric success of Nirvana’s Nevermind late that year revolutionized the notion of what could be popular, knocked Michael Jackson’s Dangerous off the top of the Billboard charts, and ushered “alternative culture” into the mainstream. Jane’s Addiction plays a de facto supporting role in this fable, since the popularity of Lollapalooza – the itinerant music festival founded that summer by Jane’s front man Perry Farrell – is commonly acknowledged as a harbinger of what was to come. In this sense Nothing’s Shocking could be seen as the voice crying in the desert, prophetically anticipating Nevermind’s messianic moment. But for me, at that time in my life, the songs on that album weren’t about zeitgeist or historical cause-and-effect so much as the way they made me feel when I listened to them.

Jane’s Addiction was the last band to play that day at Sandstone Amphitheater, and they took the stage in the darkened cool of the late-July evening. They opened with “Up the Beach,” closed with “Ocean Size,” and played “Summertime Rolls” during the encore; I watched, enraptured, from a fenced-off general-admission lawn 150 yards away from the stage. To this day it remains the most affecting rock performance I’ve ever witnessed in person – less for its artistic virtuosity than for the way it made me yearn for everything in my life that was about to happen.