Museums honor achievement, but finding original travel experiences amid their exhibits can sometimes be a challenge.

By Rolf Potts

The first time I was in Paris, I went to the Louvre and — like a million other tourists before me — headed straight for the Mona Lisa.

Since the famous French museum houses one of the most extensive art collections in the world, I’ll admit that making a beeline for a painting I’d already seen on countless refrigerator magnets and coffee mugs was a wholly unimaginative act. In tourist terms, hurrying through hallways of miscellaneous masterpieces to seek out the Mona Lisa was kind of like picking one harried celebrity from a crowd of a thousand interesting people and bugging her with questions I could have answered by reading a gossip magazine.

Apparently aware of this compulsion for artistic celebrity-worship, Louvre officials had plastered the gallery walls with signs directing impatient tourists to the Mona Lisa, and I soon fell into step with crowds of Japanese, European and North American tourists eager for a glimpse of Da Vinci’s famous portrait.

Anyone who’s been to the Louvre, of course, will know that I was setting myself up for an anticlimax. The Mona Lisa was there all right — looking exactly like she was supposed to look — yet this was somehow disappointing. Standing there, staring at her familiar, coy smile, it occurred to me that I had no good reason why I wanted to see her so badly in the first place.

Moreover, once I’d left the Mona Lisa gallery and moved on to other parts of the Louvre, I discovered just how ignorant I was in the ways of art history. Surrounded by thousands of vaguely familiar-looking paintings and sculptures, I realized I had no clue as to how I could meaningfully approach the rest of the museum.

Fortunately, before I could fall into touristic despair, I was saved by the Baby Jesus.

I don’t mean to imply here that I had some sort of spiritual epiphany in the Louvre. Rather, having noted the strange abundance of Madonna-and-Child paintings in the museum’s halls, I resolved to explore the Louvre by seeking out every Baby Jesus in the building.

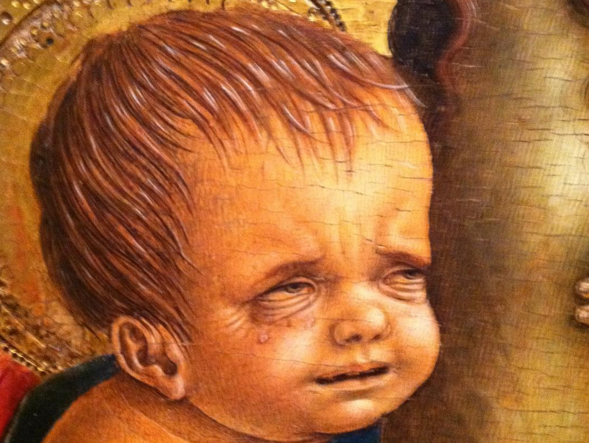

Silly as this may sound, it was actually a fascinating way to ponder the idiosyncrasies of world-class art. Each Baby Jesus in the Louvre, it seemed, had his own, distinct preoccupations and personality. Botticelli’s Baby Jesus, for example, looked like he was about to vomit after having eaten most of an apple; Giovanni Bolfraffio’s Baby Jesus looked stoned. Ambrosius Benson’s Baby Jesus resembled his mother — girlish with crimped hair and a fistful of grapes — while Barend van Orley’s chubby Baby Jesus looked like a miniature version of NFL analyst John Madden. Francesco Gessi’s pale, goth-like Baby Jesus was passed out in Mary’s lap, looking haggard and middle-aged; Barnaba da Modena’s balding, doe-eyed Baby Jesus was nonchalantly shoving Mary’s teat into his mouth. Lorenzo di Credi’s Baby Jesus had jowls, his hair in a Mohawk as he gave a blessing to Saint Julien; Mariotto Albertinelli’s Baby Jesus coolly flashed a peace sign at Saint Jerome.

Moving through galleries full of European art, these Baby Jesuses hinted at the diversity of human experience behind their creation, and ultimately redeemed my trip to the Louvre. What had initially been a huge and daunting museum was now a place of light-hearted fascination.

I’m sure I’m not the first person who lapsed into fancy when faced with a museum full of human erudition and accomplishment. To this day, I’m still never quite sure what I’m supposed to do, exactly, when I visit museums. Sure, there’s much to be learned in these cultural trophy-cases, and visiting them is a time-honored travel activity — but I often find them lacking in charm and surprise and discovery. For me, an afternoon spent eyeing pretty girls in the Jardin des Tuileries has always carried as much or more promise than squinting at baroque maidens in a place like the Louvre.

Part of the problem, I think, is that museums are becoming harder to appreciate in an age of competing information. Back in the early 19th century, when many of the world’s classic museums were founded, exhibiting relics, fossils and artwork was a way for urban populations to make sense of the world and celebrate the accomplishments of renaissance and exploration. Now that these items of beauty and genius can readily be accessed in digital form, however (where they compete for screen-time with special-interest porn and YouTube parodies), their power can be diluted by the time we see them in display cases and on gallery walls.

In this way, museums are emblematic of the travel experience in general. In 1964, media critic Marshall McLuhan wrote that, within an information society, “the world itself becomes a sort of museum of objects that have already been encountered in some other medium.” More than forty years later, that “museum of objects” has been catalogued in ways that even McLuhan could never have imagined — this means that seeing Baby Jesuses where you had expected Mona Lisas might well be a worthwhile strategy outside of museums as well.

In the purely metaphorical sense, of course.

Tip sheet: How to get the most out of museums on the road.

Having just confessed to my own bemusement in the presence big museums, I do have a few suggestions. Many national museums are so extensive that it’s impossible to experience them meaningfully in a single visit. Thus, study up a little before you go, and isolate yourself to one wing or hall of the museum. Make yourself an expert-in-training on, say, one period of Chinese history, or one phase of Dutch art. Don’t just watch the exhibits; watch how people react to them. Be an extrovert, and engage your fellow museum patrons on the meanings and significance of the displays.

If studying up beforehand seems too deliberate for your tastes, approach a big museum as if it were a highlight-reel of history or culture. Walk through the museum slowly and steadily, front to back, noting what grabs your attention. After the initial walk-though, go back to the area that interested you the most and spend some time there. Take notes, and read up on your new discoveries when you get home.

2) Make the most of small museums.

Small community museums can be found in all corners of the world, and they offer a fascinating example of how local people balance the relationship between themselves and the rest of the world. Because their exhibits are humble and anonymous compared to the likes of the Louvre, there is no set of expectations, and no tyranny declaring that you must favor one relic or piece of art over another. Much of the time, this better enables you to see things for what they are (instead of what they are supposed to represent). The secret to exploring these small museums is their curators (and their regulars), who are invariably knowledgeable and a tad eccentric. Take an interest and ask lots of questions, because these local experts will have plenty to share.

3) Let the world be your museum.

If the world itself has become a museum of objects, treat it with the same attention and curiosity you would a formal gallery. As tourist scholar Lucy L. Lippard has noted, a shopping mall, a thrift store, or even a junkyard can be as revelatory in a faraway place as a gallery full of relics. Similarly, daily life in a given neighborhood off the tourist trail is just as likely to reveal the nuances of a given culture as is an official exhibit. Wherever you go as you travel, allow yourself to wander, ponder, and ask questions. Odds are, you’ll come home with a deeper appreciation of a place than if you were just breezing from one tourist attraction to another.

This essay originally appeared in Yahoo! News on November 6, 2006.