One of the writing projects I’ve been working on this winter is Last Nine, a coming-of-age screenplay I’ve been chipping away at for more than a decade now. Built around a single incident I remember from my high school Spanish class when I was 17 years old, Last Nine tells the story of a teenager whose world begins to shift when he makes a new group of friends in the weeks just before he graduates from high school.

Though I know screenwriters have little control over the soundtrack once the movie has been produced, I’ve written Last Nine with the sense that Woody Guthrie’s cover of The Carter Family’s “Will You Miss Me When I’m Gone,” will play as the characters assemble for the last time, in the final scene. This somber, sentimental folk song will set just the right tone — or, more accurately, the right sense of ironic juxtaposition — as the characters leave home (in their own, low-stakes way) for the first time.

Music plays an important role in all movies, but individual songs have always had a pointed presence — and psychic resonance — in coming-of-age movies. Some of my strongest memories as a moviegoer have come in those ineffable moments when a strategically chosen song intensifies the emotional impact of an entire film.

I’ve listed my 12 favorite end-of-movie song moments here, along with my thoughts about why these music choices were so effective. I’ve focused on stand-alone songs rather than film-score music, which leaves out a handful of resonant coming-of-age movies that end with variations on the story’s theme music (such as Maurice Jarre’s stirring theme to Dead Poets Society, and Nicholas Britell’s heartbreaking leitmotif from Moonlight). I’ve itemized them here less by “rank” than by how I’ve come to remember them.

[Note: A podcast companion to this article is online here.]

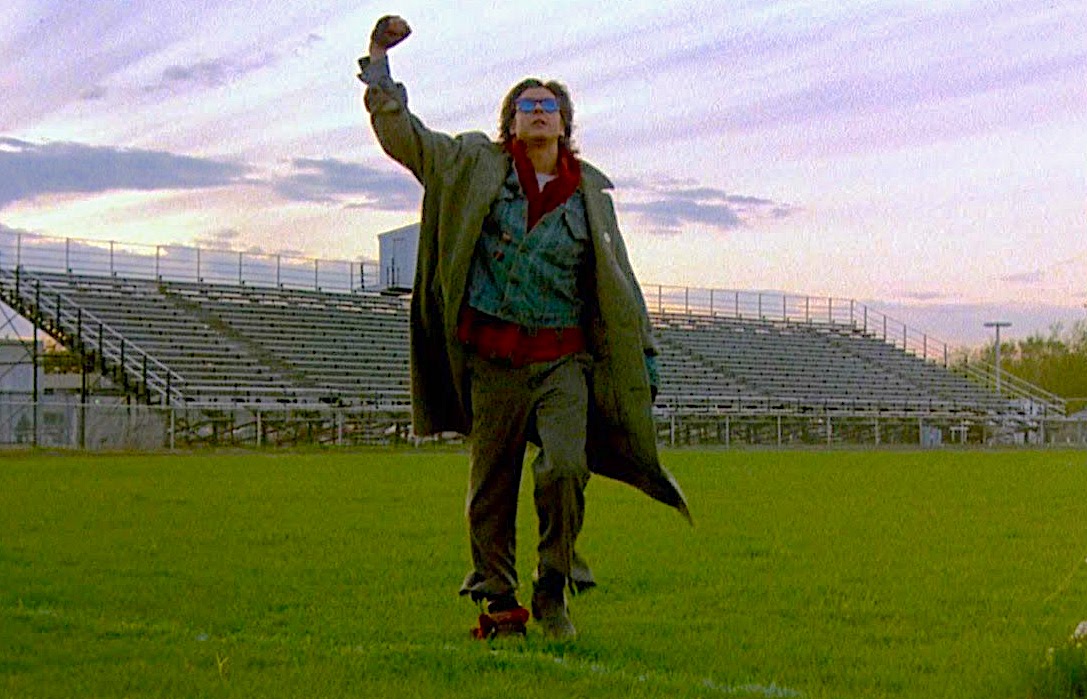

Simple Minds’ “Don’t You (Forget About Me),” from The Breakfast Club

This is a quintessential end-of-movie song, from a quintessential teen-movie ending-scene, written and directed by quintessential teen-movie auteur John Hughes. I remember watching The Breakfast Club on VHS at age 15, in 1986, and thinking that Hughes had achieved something singular and true to teenage life.

Years later, it feels like the confessional soliloquies (and sudden romantic pairing-off) among the disparate characters of The Breakfast Club were more idealized than realistic. Still, there’s no question it was a groundbreaking movie in terms of how American teenagers — and their fears, hopes, and preoccupations — were portrayed on the screen. “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” underscores the stakes (who are these kids, and what will they mean to each other after today?) during the film’s climactic moment of symbolic rebellion: Brian reading his “you see us as you want to see us” essay in a voice-over as Bender pumps his fist into the air and the credits roll.

Interestingly, the Scottish rock band Simple Minds were initially resistant to recording the song, which was composed by producer Keith Forsey and guitarist Steve Schiff (Bryan Ferry and Billy Idol had already turned down the opportunity). They eventually relented under pressure from their record label, and the band is now remembered for this song — and the way it evokes the triumphant final image of The Breakfast Club.

Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me,” from Stand By Me

Whereas “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” played at both the beginning and ending of The Breakfast Club, different variations of Ben E. King’s eponymous soul tune play throughout Stand By Me. I was 15 going on 16 when I first saw this movie, and somehow I found these four characters (who were 12 going on 13) to be deeply, movingly relatable.

Essayist Louis Menand has written (in the context of Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye) that nostalgia is at its keenest when we’re still young, and Stand By Me left the 15-year-old me longing for the person I was at age 12. This is not a particularly happy movie — it is, after all, about a group of boys setting off to find a dead body — but something about the way the characters confront the passing of their own prepubescent youth made me miss my own.

I had no idea Stand By Me was based on a Stephen King novella when I first saw it, but in retrospect its core plot — young characters setting off on their own, without adults, to get into adventures and battle their demons — feels very true to his greater body of work. A kind of nostalgia suffuses the movie’s narrative, not just in the fact that its sights and songs evoke small-town America in the late 1950s — but also in the fact that the story is narrated by the adult Gordie (Richard Dreyfuss), who is looking back on his youth after reading about the death of his childhood friend.

Just as “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” underscores the tenuousness of friendship in The Breakfast Club, the song “Stand By Me” ultimately serves to mourn the evanescence of the bond between the four boys in the movie, helping to articulate the sense of loss King tries to describe in the opening lines of his novella:

“The most important things are the hardest to say. They are the things you get ashamed of, because words diminish them… The most important things lie too close to wherever your secret heart is buried, like landmarks to a treasure your enemies would love to steal away. And you may make revelations that cost you dearly only to have people look at you in a funny way, not understanding what you’ve said at all, or why you thought it was so important that you almost cried while you were saying it. That’s the worst, I think. When the secret stays locked within not for want of a teller but for want of an understanding ear.”

Foghat’s “Slow Ride,” from Dazed and Confused

The passage of time has always been a thematic obsession for director Richard Linklater, from his breakout movie Slacker (see below), to his Before Sunrise/Sunset/Midnight trilogy, to his innovative multi-year coming-of-age project Boyhood. The largely plot-free Dazed and Confused takes place over the course of a single 24-hour period as it follows several interlinked groups of Texas teens on the last day of the 1976 school year. The music here is period specific and pitch-perfect, from Aerosmith’s “Sweet Emotion” in the opening scene, right up through the heady Foghat anthem that blasts in Mitch’s headphones as we see Wooderson, Pink, Slater, and Simone cruise on an open highway before the credits roll.

I saw Dazed and Confused the week it came out, in the fall of 1993, when I was living in Seattle — and I walked out of the theater in a haze, as if I had been transported back to my Kansas youth five years earlier. Somehow, Linklater’s fictional 1976 perfectly evoked what 1988 felt like to me when I was in 1993. Now — 25 years later — Dazed and Confused evokes 1993 for me as much as anything, even as it continues to call forth memories of 1988 (and 1976). Weirdly enough, 1993 was an incredibly distinctive year for me — I was 22, I had just graduated college, and I was working as a landscaper in Seattle at the peak of grunge — yet part of the way I experienced it was by yearning for a different, more provincial (and many ways less interesting) time of my own life.

The most iconic line in Dazed and Confused comes from the long-since-graduated hanger-on Wooderson (played by a then-unknown Matthew McConaughey), who says, “That’s what I love about these high school girls, man. I get older, they stay the same age.” A quarter of a century later, the same thing could be said for the movie’s characters, Wooderson included: The kids I see onscreen don’t age, which only underscores the way the way Dazed continues to remind me of multiple times of my own life — multiple, far-flung moments of being alive — as I grow older.

As a footnote here, Foghat’s “Slow Ride” wasn’t meant to be the closing track to Dazed and Confused, but Linklater couldn’t secure the rights to Led Zeppelin’s “Rock and Roll” (as the story goes, guitarist Jimmy Page was fine with it, but singer Robert Plant wouldn’t sign off). One can understand why Linklater would want this song for the movie (which itself was named for a Led Zeppelin song), though in retrospect “Slow Ride” is a pretty perfect way to end the film.

Eddie Vedder’s “Hard Sun,” from Into the Wild

I came late to Sean Penn’s movie adaptation of Into the Wild — in large part because I didn’t think it would have much new to offer, having already read and enjoyed Jon Krakauer’s book. When I finally did watch it, the movie’s depiction of Alexander Supertramp’s doomed American pilgrimage affected me in a way that was far more intuitive and personal than the book. That’s the power of movies, I think, at least when they work well: They capture feeling in a way that goes beyond factual or intellectual content.

Which is to say that, while Krakauer’s book was engrossing, the movie version of Into the Wild was relatable in a way I hadn’t expected it to be. On the written page I could see how Christopher MacCandless’s life might be similar to my own (I was 21 the month he died, and had gone on solo treks in Washington’s Olympic Peninsula that same summer), but on the screen it felt like his life-journey was inseparable from the same heady ideals that sent me off on my own vagabonding path at around the same time in life. Like Chris, I jumped trains and wandered the American West when I was in my early twenties, drawing my inspiration from dog-eared volumes of Thoreau and Whitman and Edward Abbey. Like Chris, I was addicted to newness and possibility; I put myself through countless little self-initiatives in the wilderness, and I found something sacred in my gradual accumulation of adventures.

I’ve often said that Vagabonding, the book that resulted from my youthful wanderings, was meant as a kind of letter to my 17-year-old self — and after watching Into the Wild I was reminded of how, when you’re young, there are two inherent dangers to the youthful urge for freedom and purity. One is that you’ll be too timid to actually break free and wander — but the other is that you will over-romanticize the journey once it’s underway, which can be less-than-ideal for both yourself and the people you leave behind. Into the Wild, both the book and movie, serve as a kind of cautionary tale against this impetuous, cocksure, self-mythologizing romanticism — even as Chris’s story continues to inspire a slew of pilgrims and imitators.

Considering what happened to MacCandless/Supertramp, Into the Wild is a decidedly dark coming-of-age tale, but somehow Eddie Vedder’s folky score — and in, particular, his soulful cover of Gordon Peterson’s “Hard Sun” in the final scene — underpins the story with a hopeful sense of existential yearning.

Freedy Johnston’s “Bad Reputation,” from Kicking and Screaming

Around the early-mid 1990s a number of self-consciously hip movies were made with the “Generation X” youth market in mind — think Reality Bites, Singles, Empire Records, etc. — but few were quite so funny and poignant as Kicking and Screaming, indie auteur Noah Baumbach’s 1995 debut. Plot-wise, the movie doesn’t amount to much — it’s about a group of four friends who can’t quite leave college after having graduated — but its loquaciously depressed (and affably clueless) characters epitomze the existential stasis that can grip young men at the very moment they’re supposed to be making something of themselves in life.

A sentimental part of me is convinced that I watched this highly relatable movie at the exact same phase of life as Grover, Max, Otis, and Skippy, its quartet of recently graduated characters. In truth, I saw it nearly three years after college graduation, while I was stuck in a personal/professional dead spot between the successful completion of my first vagabonding journey, and my eventual move to Korea to teach English (and prolong my vagabonding adventures).

Kicking and Screaming is in part about the sudden loss in social status that accompanies graduation, when one is tossed out of the small pond of college and into the churning ocean of life — and somehow the characters’ self-imposed paralysis and suffering in the face of the rest of their lives made my own situation feel a little bit more tolerable. The four main characters all wear sports jackets — as if, Baumbach has noted, they are children playing at being adults — and I was so taken by this affectation that I bought a sports jacket to wear at work when I struck off for Korea in late 1996.

By far the most mature characters in Kicking and Screaming are the protagonists’ long-suffering girlfriends, and the movie’s climactic moment comes when Grover (played by Josh Hamilton) finally makes the decision to go and join his erstwhile paramour Jane (Olivia D’Abo) in Prague. “It’ll make a good story of my young adult life,” Grover says as he psyches himself up at the airline counter. “You know, the time I chose to go to Prague.”

This penultimate (and ultimately, for Grover, not-quite-actualized) airport departure scene is followed by one of my all-time favorite movie-endings — an understated flashback that details the moments before Grover and Jane’s first kiss many months earlier. It sounds corny even just typing it here, but somehow — in the moment just before Johnston’s “Bad Reputation” kicks in — Grover’s soliloquy to Jane about wishing they were an old couple (followed by Jane’s self-consciousness about whether or not to take out her retainer) strikes the ideal tone of romantic awkwardness.

Led Zeppelin’s “Tangerine,” from Almost Famous

Cameron Crowe’s largely autographical tale of traveling America via rock-n-roll tour-bus as a 15-year-old Rolling Stone journalist isn’t as directly relatable as the other coming-of-age movies I’ve mentioned, but it’s every bit as much fun. Many of the movie’s best moments hinge on music — perhaps none quite so ecstatically as when the entire cast screams along to Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” after a band fallout (and reunion) in Topeka — and Led Zeppelin’s “Tangerine” provides a nice coda to the moment Will Miller (Patrick Fugit) and Russell Hammond (Billy Crudup) finally — after so many miles on the road together — sit down at Will’s home to discuss music in an open-hearted way.

The Faces’ “Ooh La La” from Rushmore

Much has been said about director Wes Anderson’s visual style, but his musical choices are just as distinctive — and in Rushmore, Anderson’s iconic 1998 sophomore effort, the movie’s soundtrack is as much of a character as Jason Schwartzman’s overachieving teen Max Fischer, or Bill Murray’s middle-aged mogul Herman Blume. Our introduction to Max’s overblown extracurricular ambitions wouldn’t be the same without the yearbook montage set to Creation’s “Making Time,” and the Max-versus-Herman revenge sequence achieves its bitter culmination to the tune of The Who’s “A Quick One, While He’s Away.” Rushmore‘s final scene finds its consummate tone thanks to The Faces’ bittersweet 1973 tune “Ooh La La.”

The Magnetic Fields’ “Saddest Story Ever Told,” from The Myth of the American Sleepover

David Robert Mitchell’s breakout movie was a creepy 2014 teen-sex horror movie called It Follows — but his cinematic debut came three years earlier, with the release of The Myth of the American Sleepover, which was shot in Michigan on a shoestring budget and never went into wide theatrical release. I happened to see it by dumb chance at Angelika Film Center while visiting New York in the summer of 2011, and I was enamored by the way this understated film (full of unknown actors) captured something tangible and resonant about teenage life.

The irony here is that there’s a deliberate vagueness to The Myth of the American Sleepover, since it doesn’t seem to take place during any specific time period. It feels somewhat contemporary, for example, yet none of the characters use cell phones or the Internet — and the late-summer “sleepovers” implied by the title feel quaint and anachronistic, even as the experiences the characters have there feel emotionally specific and relevant. Sleepover doesn’t have an epiphanic ending like The Breakfast Club (or an ebullient one like Dazed and Confused), but The Magnetic Fields’ “Saddest Story Ever Told,” coupled with Balthrop, Alabama’s “Love to Love You,” strike the right emotional note to this surprisingly affecting film once the credits roll. (Both songs also feature in the movie’s trailer.)

Horst Wende and His Orchestra’s “Skokiaan,” from Slacker

Richard Linklater’s second feature barely qualifies as a coming-of-age film, since Slacker‘s camera rarely lingers on one character for very long, and none of them appear to transform in any discernible way. Still, there is something joyful and energizing about the final sequence of the movie, when a group of youthful characters film themselves driving (and then climbing) to the top of Mount Bonnell near Austin. “Skokiaan” is a 1947 pop tune by Zimbabwean musician August Musarurwa, and it’s most famous rendition is probably Louis Armstrong’s 1954 version — but German bandleader Horst Wende‘s peppy 1958 cover strikes a nice retro tone for the final frames of Slacker.

In the DVD commentary track to the movie, Linklater says that this final sequence — which seems to presage the way young people in the smartphone age hyper-document their own lives — was inspired by a Bill Daniel short film. Linklater had hoped to cap the film with Peggy Lee’s 1969 rendition of Leiber and Stoller’s “Is That All There Is?” but had to settle for “Skokiaan” and the Butthole Surfer’s “Strangers Die Everyday” when he couldn’t secure rights to the Lee song. To my ear, the creepy strains of “Strangers Die Everyday” provide a better emotional texture as the Slacker credits roll, since “Is That All There Is?” feels a tad on-the-nose for such a quirky movie.

Third Eye Blind’s “Semi-Charmed Life,” from American Pie

Though Paul and Chris Weitz’s teen-sex comedy American Pie came out in 1999, it feels very much like a 1980s movie — and it was probably the last time I watched a teen movie with a faintly teenaged sensibility. The truest homage to American teenage life that came out in 1999 wasn’t a movie — it was the TV show Freaks and Geeks (which, to my mind, was the truest on-screen evocation of Middle American adolescence ever made). Yet while the comic hyperboles of American Pie don’t ring quite as true as Freaks and Geeks, it was a delightfully entertaining coming-of-age-by-trying-to-lose-your-virginity movie.

I had been backpacking around Asia and Eastern Europe for most of 1999, and while I was probably a bit too old the properly appreciate the soundtrack, the songs that feature in the movie’s final scene — Third Eye Blind’s “Semi-Charmed Life” and Bare Naked Ladies’ “One Week” — take me back to that year I spent wandering the East (as do other one-hit wonders from around that same time, like Fatboy Slim’s “The Rockafeller Skank,” Blink-182’s “All The Small Things,” Chumbawamba ‘s “Tubthumping,” Smash Mouth’s “Walkin’ On The Sun,” and The Verve’s “Bitter Sweet Symphony.”

Yello’s “Oh Yeah,” from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

I positively loved Ferris Bueller’s Day Off when it came out in 1986, and it remains one of my favorite teen movies. People have, in retrospect, disparaged the Ferris Bueller character as a bit of a privileged snot — but it was clear to me even as a teenager that Ferris Bueller’s Day Off was less a realistic commentary on teenage life than a whimsical fantasy movie that set out to have as much fun as possible with its premise.

Moreover, it’s easy in retrospect to forget just how singular a character Ferris was: At a time when teen movies had for generations been characterizing protagonists in terms of clique-driven stereotypes, Ferris was unique to himself — a smart, quirky, hyper-articulate (and not-necessarily athletic or hyper-masculine) friend-to-everyone who walked through the world on the irrepressible strength of his own charisma. “Oh Yeah,” Yello’s singularly weird instrumental track, set the perfect end-of-movie texture as the credits rolled and Principal Rooney got his comeuppance (and Ferris himself shooed us out of the theater).

David Bowie’s “Heroes,” from The Perks of Being a Wallflower

For reasons I can’t fully explain, I discovered and read (and loved) Stephen Chbosky’s 1999 YA-market novel The Perks of Being a Wallflower when I was in my late thirties. At a logical level the story itself doesn’t quite make sense — the protagonist is a freshman misfit who seamlessly falls in with a bunch of hip seniors (and somehow has superhuman physical strength). Yet, weirdly, on an emotional level the story is spot-on in its evocation of adolescent yearnings, particularly as expressed through songs like The Smiths’ “Asleep.”

The movie version of Wallflower, which was directed by Chbosky himself, didn’t quite work for me — though the final scene (when Charlie races through Pittsburgh’s Fort Pitt Tunnel in the back of a pickup, declaring, in voice-over, that “we are infinite”) makes for a great ending. In the book this scene takes place to Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide”; in the movie the song is swapped out with David Bowie’s “Heroes” — and it’s a choices that strikes the perfect tone as the film cuts to credits.

Note: I don’t host a “comments” section, but I’m happy to hear your thoughts via my Contact page.