1) On the essential hardship of travel in the ancient world

As late as the end of the fourth century BC, travel in and around Greece was neither easy nor particularly pleasant. Those who went by sea depended on the sailings of merchant-men, put up with casual accommodations once abroad, and worried about pirate attacks during the whole voyage. Those who went by land found the roads generally poor, the inns worse, and had to keep a sharp eye out for highwaymen. The wealthy were better off only in having the money to take a cabin aboard ships that offered such amenities, friends to put them up in various places, and the influence to ensure the help of their city’s proxenos if they got into difficulties. Most who traveled did so with specific ends in view: government representatives, businessmen, itinerant merchants, actors on tour, the dick heading for a sanctuary of Asclepius, the festival crowds en route to the Panhellenic or other well-known games. But there were a few who, despite all the discouragements, traveled for the love of it.

2) On land travel in the ancient world

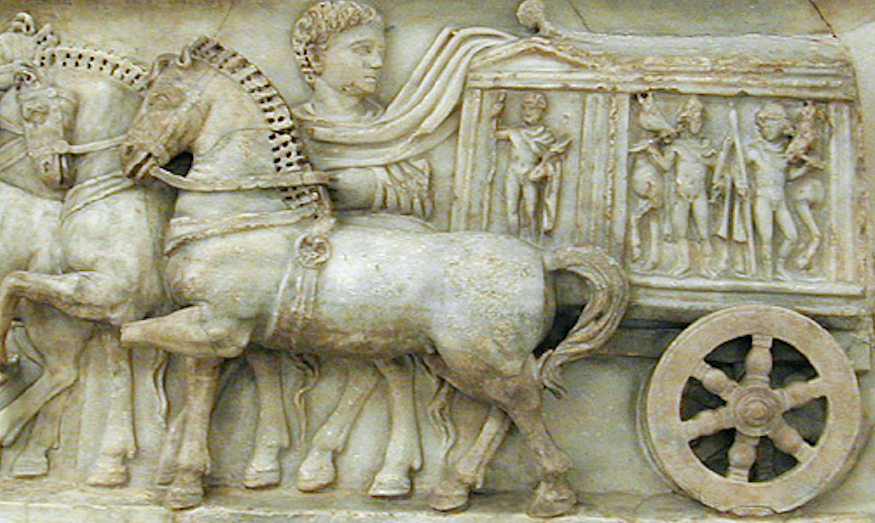

Travel by land in this age was strenuous. It usually meant going on foot. People traveling light took along only a slave or two to serve as valet and carry the baggage, sacks stuffed with clothes, bedding, and provisions. More elaborate entourages included a goodly number of servants and pack animals for the gear. With rare exceptions, these were donkeys or mules; horses, as we observed before, we for racing, hunting, or the army. The animals would have a sheepskin or goatskin thrown over their backs to prevent chafe and, upon this, a wood-frame packsaddle often fitted with panniers. Those who could afford it sometimes took donkeys or miles for riding as well. The Greeks looked down on the litter or sedan-chair; it smacked of ostentation, they felt, and condoned its use only in the case of invalids or women.

3) On sea travel in the ancient world

There were no such things as passenger vessel in the ancient world. Travelers did as they were to do until the packet ship finally made its debut in the nineteenth century: they went to the waterfront and asked around until they fond a vessel scheduled to sail in a direction they could use. Since the vessels were first and foremost for cargo and carried passengers only incidentally, they provided neither food nor services. The crews were solely for working ship; there were no stewards among them to prepare meals or tend cabins. As in earlier times, voyagers went aboard with their own servants to take care of their personal needs and with supplies of food and wine (the ships did furnish water) to sustain them until the next port of call where there would be a chance to obtain replenishments.

4) On lodging in the ancient world

In the early days, travelers often had no alternative to using private hospitality. And private hospitality continued to play a significant role long after the increased pace of movement had planted inns all over the land. Traders counted on being lodged with business associates, the noble or wealthy with their influential friends, and the humble with whoever would take them in. Families in different cities united by ties of friendship extended hospitality to each other from generation to generation. The ties did not have to be particularly close; indeed, there were certain households with the generous tradition of putting up all citizens from a given place regardless of whether these were personally known or not. The dwellings of the well-to-do always included at least one xenon or guest room; usually it had its own entrance, and sometimes it was a separate little lodge. The visitor would be invited to his host’s table the day after his arrival; thereafter provisions were sent to the xenon or he bought them himself, and his servant prepared them. On departure, guest and host exchanged gifts.

5) On travel clothing in the ancient world

There was one problem the Greek traveler was spared: harrowing decision about what clothes to take. The basic garment for men was the chiton, a loose sleeveless linen or woolen tunic which came down to the knee or calf and was gathered in around the waist with a belt, the zone. When traveling, men tended to double their chiton over the belt to draw it up higher and, in that way, leave the legs free and keep the hem out of the reach of dust or mud. For outer covering the traveler carried a chlamys, an oblong of wool that could be worn as a short cape. On his feet he tied sandals securely with thongs reaching to the calf; he wore no socks or stockings since these were all but unknown throughout ancient times. On his head he clapped a sort of sombrero, the petasos, a wide-brimmed hat fitted with a chin strap; in hot weather the could uncover simply by letting the hat slide down his back and hang from the strap, while in cold he could pull the strap tight in such a way that the brim closed in and covered his ears. His wife would have a tunic like his, and, as headgear, a chic version of the broad-brimmed hat; she might also carry a parasol. She had no short cloak, just the large oblong of wool which she would wear as a mantle draped about her. Whatever was not on their backs was packed up into cloth sacks and put in the care of the slaves who accompanied them. Only exiles, refugees, or the like traveled alone; ordinary voyagers invariably took along at least one servant.

6) On managing travel funds in the ancient world

Money posed the most serious concern of all because, with no instruments of credit available. It had to be carried in coin. A businessman could probably limit the amount he took and count on replenishing his funds from his associates abroad, and the aristocrat no doubt made reciprocal arrangements with the friends and relations who would put him up in the various places he visited. But even if they had to carry some cash with them, while the rank and file of, say, those heading for one of the great festivals had to take enough to cover all expenses while away from home. Greek bandits could be pretty sure that their efforts would be rewarded, that any traveler they pounced on would have a fairly well-filled purse on him.

7) On the necessity of day-travel in the ancient world

Ancient travelers made it a rule to arrive by daylight. In an age that did not know the lighthouse, let along beacons or illuminated buoys, no skipper wanted to enter a harbor in the dark. Walkers or riders were just as averse to threading their way at night through unmarked, unpaved, and unlit streets, unable to see either their way or where to jump when they heard “Stand back!” and rubbish came flying out of a window. Street lamps lay centuries into the future, and paving was not only rare but, where it did exist, just a poorly drained alter of stone chips rammed into the surface. To add to the confusion, those most useful devices, street signs and house numbers, were yet to be invented. …By arriving during the day the stranger could at least step around potholes, avoid piles of refuse, see where to duck in at the warning call of someone throwing rubbish, find passersby to ask the way, and stand some chance of following their instructions successfully.

8) On museums in the ancient world

For a museum that begins to approach what we generally mean by the term we must go down in time to the first half of the sixth century BC, the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. He and his successor were particularly interested in the past, they studied archaic inscriptions, they restored old buildings, they even conducted archaeological excavations to locate the foundation stones of ancient temples. So it comes as no surprise to discover that Nebuchadnezzar II installed in an area of his palace a collection of objects stemming from bygone times. He named it the “Wonder Cabinet of Mankind,” and opened it to the general public. It was for all intents and purposes a museum of historical antiquities.

9) On travel souvenirs in the ancient world

Inevitably, the ancients had their versions of the cheap, gimcrack souvenir. Thanks to the archeologists, we have quite a few examples to show what these were like. In the second century BC shops in Alexandria sold a distinctive type of cheap faience pot with a figure in relief on it of one of the Ptolemaic queens; though intended primarily for the local folk — most examples have turned up in Egypt — it also appealed to visitor, who carried them off as souvenirs. The Bay of Naples area, Rome’s favored holiday area, offered a typical tourist item, little glass vials bearing pictures of the chief sights in the region identified by labels: “Lighthouse,” ” Palace,” “Theater,” “Nero’s Pool,” “Oyster Beds,” etc.