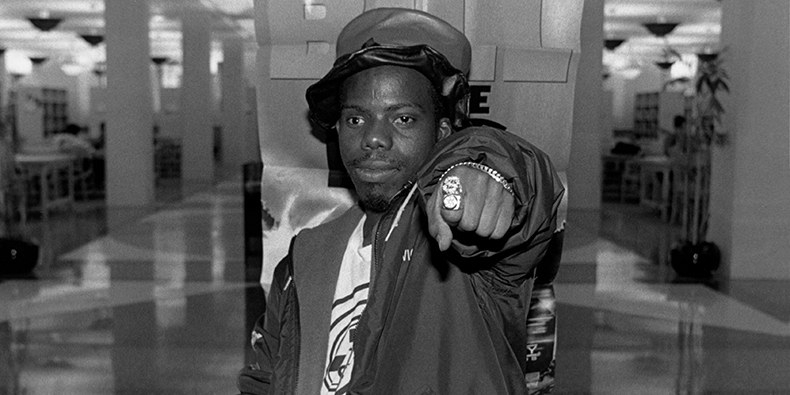

Of all the times I’ve been name-checked in the Washington Post, the most counterintuitive occasion came last month, when it appeared in an obituary for Bushwick Bill, the one-eyed, 3’8″ gangsta-rapper most notable for his work with the Geto Boys. Specifically, the obit alluded to my 2016 book The Geto Boys, which was part of Bloomsbury’s 33 1/3 series of books about iconic music albums.

Though my book chronicles the rise of the Geto Boys in 1980s Houston, it is at heart an exploration of the psychogeographical power of gangsta rap – of the way it sought to mythologize (rather than be ashamed of) the poorest neighborhoods in America. Just as NWA celebrated Compton rather than Los Angeles proper, the Geto Boys made Houston’s Fifth Ward sound as foreboding (and fascinating) as the land of Mordor. The Geto Boys’ lyrics frightened me in a way the tough-guy theatrics of late-80s metal and punk-rock did not. During my first vagabonding trip around North America 25 years ago, my biggest motivation for going through Houston was to venture into the Fifth Ward – which I did, on a cool night that February.

I framed my recollections of this experience with 150 years of Texas-historical and socio-musicological context – and thus my book’s argument for the relevance of the Geto Boys is rooted in the faintly cerebral nuances of psychogeography. Three years on, however, I wonder if I shouldn’t have more explicitly focused on the Geto Boys’ gleeful embrace of offensiveness. In an era when it has become an intellectual parlor-game to identify sub-textual transgressions in old cultural products like Kinks songs and David Foster Wallace novels and John Hughes movies, the Geto Boys’ decision to use unvarnished offensiveness as its own distinct vernacular feels relevant – if only as a way to make this discussion more modulated and multivalent and honest.

Though the Geto Boys are largely remembered for their 1991 hit “Mind Playing Tricks On Me” (as well as their delightfully ironic soundtrack-appearance in the 1999 cult-movie Office Space), their biggest contribution to popular culture may well have been the way their overt lyrical offensiveness wound up refracting the social discussion of what we mean when we use that word. I explore this a bit in the book, since Bushwick Bill himself had a way of trolling the media about the group’s lyrics. When asked about the Geto Boys’ influence on the wellbeing of young Americans, Bushwick would cite the president’s plans to send thousands of young Americans to war in Iraq; when asked about the limits of constitutional free speech, Bushwick would point out that the Constitution once considered black people to be three-fifths human.

RIP, Bushwick Bill. Hollywood may never bestow you with your own biopic (as it did with NWA), but you certainly pushed music – and the discussion surrounding it – into a more interesting direction.

Note: I don’t host a “comments” section, but I’m happy to hear your thoughts via my Contact page. To learn more about what this blog is all about, read items #2 and #3 from my update post.