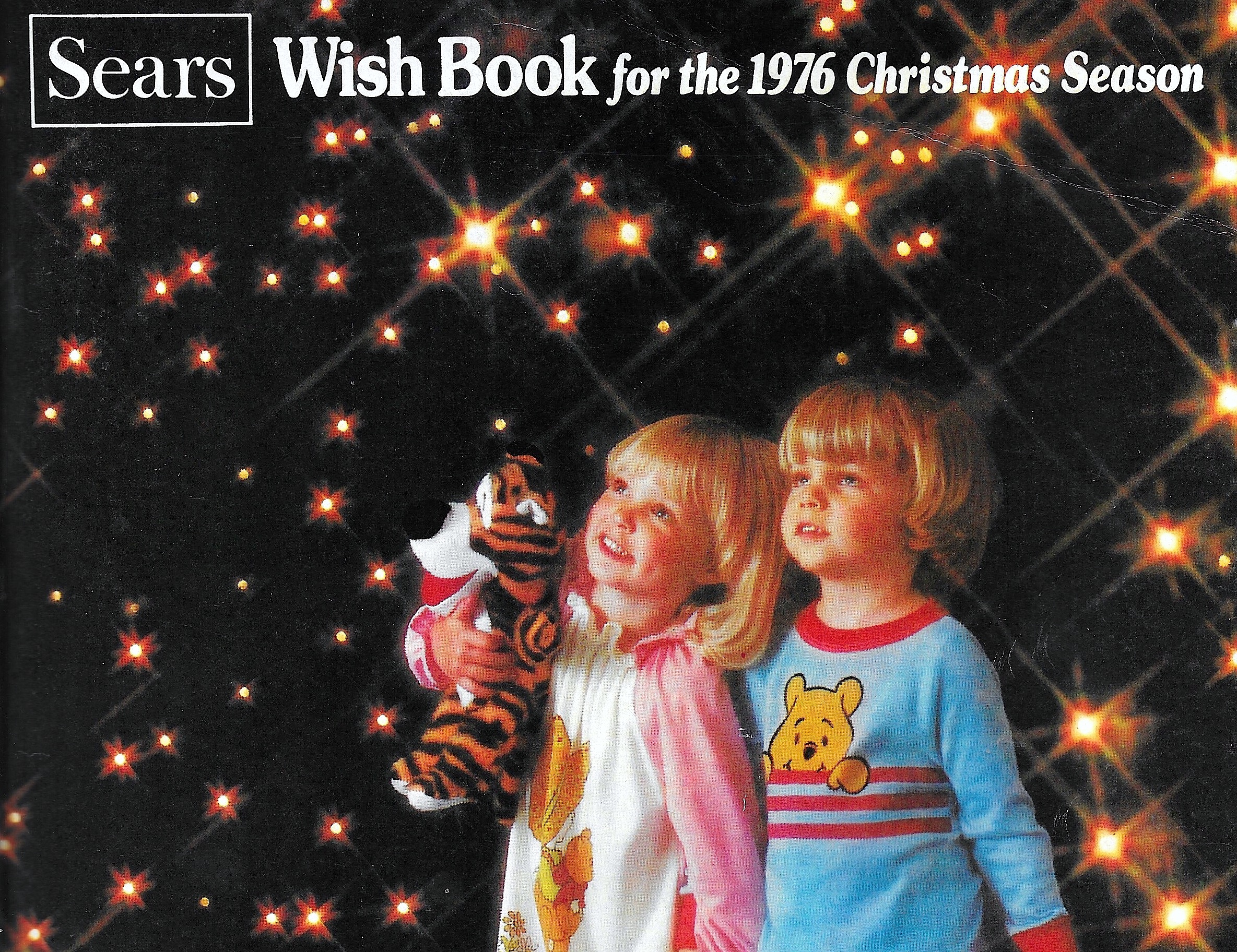

When I think back on the most affecting literature I read in my youth, the 1976 Sears Christmas Wish Book instantly comes to mind. I was obsessed with it when I was six years old — much like Stephen King’s Night Shift would capture my imagination when I was 13, Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions when I was 17, and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass when I was 22.

I realize that mail order catalogs are not considered literature in the same sense as, say, Leaves of Grass. But in practice the Sears Christmas Wish Book was, for me, a kind of foundational text — a secular counterpoint to the Bible stories I learned around that time in Sunday School. Even though I could scarcely read in 1976, I paged through the holiday catalog’s 620 glossy pages as if they amounted to an intoxicating graphic novel of desire, rich with abundance and possibility.

By that time in life I was familiar enough with the Wish Book that I anticipated its arrival by mail just before Thanksgiving. Thematically, the catalog was split into two equal halves, neatly divided by an index and order forms in the middle. The front half — clothing and household items — didn’t much interest me, so I always opened it from the back, so I could flip through pages of toys and electronics. I was four months into kindergarten at the time, and I used my newly acquired writing skills and a school tablet to itemize, by page number, which items I wanted Santa to bring me that year.

I learned this annotation method from my sister Kristin, who was two years older than me. While Kristin’s wish list was tasteful and pragmatic, however (usually limited to dozen or so items she figured she stood a chance of getting) my notations were exhaustive, encyclopedic. The 1976 Wish Book gave name to desires I never knew I had, and I listed them all: model airplanes and NFL-logo AM radio sets; popcorn poppers and Tinker Toys; air-hockey tables and refractor telescopes; boxed chocolates and polyethylene toboggans; chess sets and metal detectors. I knew I could never receive all these items, but that didn’t matter, since I regarded the catalog as a kind of self-referential fantasy novel.

Though my Sears Wish Book list grew to more than 200 items that year, Santa brought me exactly one of them — a sports-themed wastebasket similar to the ones depicted on page 412. Tellingly, my parents decided to save on postage and purchase it from a local discount store, so my trash bin featured Wide World of Sports athletes instead of NFL team logos. I still tell this story to people when I want to illustrate my parents’ utilitarian Midwestern frugality (and I still have the wastebasket; it sits in a place of honor in my spare bedroom.)

Earlier this year I went online and bought a copy of the 1976 Sears Wish Book from a vendor on eBay. Leafing through its pages has in part been an act of nostalgia — but 40 years of retrospective have also helped me realize how the catalog was product of a vibrant and uniquely American literary tradition that predated it by nearly a century. Indeed, to understand the 1976 Wish Book represented, one must travel back to the year 1888.

How the Sears Catalog Made America America: A Brief History

In the same way that improvements in European sailing and navigation techniques gave rise to popular travel-romance literature in the seventeenth century, mail-order catalogs are the direct result of transportation technology — specifically the spread of railroads into the American West in the late nineteenth century. American railroad companies created standardized time-zones in 1883 to make their transport routes more efficient, and this generated a demand for watches. In 1886 a jeweler’s clerical error left a Minnesota station agent named Richard Warren Sears with a surplus of pocket watches, and instead of sending them back to the supplier in Chicago, he sold them at a profit to station agents in more far-flung locations.

The demand for watches and other manufactured products proved so great in the American West that in 1888 Sears began to send out printed mailers to advertise and sell other goods. The first edition of Sears’ mail-order catalog featured watches and jewelry — but it soon expanded to include clothing items, musical instruments, books, sporting goods, sewing machines, saddles, shop tools, firearms, bicycles, baby carriages, and horse buggies. The 1895 catalog sold eyeglasses, complete with a self-test for “old sight, near sight and astigmatism”; the 1902 catalog sold opium (a common homeopathic remedy at the time). Starting in 1908 Sears’ catalog began to sell ready-to-assemble houses, complete with tools, nails, and building instructions.

It’s hard to overstate how much the Sears catalog (and its competitors, like Montgomery Ward and Hammacher Schlemmer) transformed rural American life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Whereas the people who lived in isolated frontier towns and farmsteads once had to haggle over a limited selection of items at local general stores, mail-order catalogs now brought these folks a rich variety of products at fixed prices. Far-flung rural communities once beholden to traditional folkways were now connected (if only at the level of longing and imagination) to the technology, fashions, and abundance of cities.

As often as not, the Sears catalog represented aspiration as much as it did commerce. Rural American values like hard work and self-improvement had always been pegged to abstractions like stability and sustenance; now every country home had a tangible index (updated each year) of the material rewards a good life might offer. As media scholar Alexandra Keller noted, “the catalog could simultaneously function as a mall between two covers and pass itself off as noncommercial, something that, like cinema, claimed to exist largely for entertainment, edification, and fantasy.” Moreover, rural schoolchildren often learned to read and calculate arithmetic by studying its product listings, immigrant adults used it to determine what was considered “normal” in American culture, and people of all ages used pages from old catalogs for outhouse toilet paper.

As often as not, the Sears catalog represented aspiration as much as it did commerce. Rural American values like hard work and self-improvement had always been pegged to abstractions like stability and sustenance; now every country home had a tangible index (updated each year) of the material rewards a good life might offer. As media scholar Alexandra Keller noted, “the catalog could simultaneously function as a mall between two covers and pass itself off as noncommercial, something that, like cinema, claimed to exist largely for entertainment, edification, and fantasy.” Moreover, rural schoolchildren often learned to read and calculate arithmetic by studying its product listings, immigrant adults used it to determine what was considered “normal” in American culture, and people of all ages used pages from old catalogs for outhouse toilet paper.

In many rural homes, the Sears and Wards catalogues were the only reading material apart from the family Bible. (Aware of this, Richard Sears designed his catalog to be slightly smaller, so folks would instinctively stack it on top of the Wards volume.) While Bibles from that era evoked spiritual concerns in the ornate Shakespearian prose of the King James translation, the Sears catalog was written in unadorned language meant to describe (and sell) a wide variety of material merchandise. According to historian Daniel Boorstin, this language — the language of advertising — was, “with its spreading power and its new freedom from pedantic and typographic bonds, already evolving into a democratic genre of literature.” In this way, the Sears catalog played a role in the rise of the simple, direct American prose that became the norm in the twentieth century.

Though the Sears catalog had featured Yuletide-themed items since 1896 (when it sold wax candles to hang on Christmas trees), it didn’t issue a holiday-specific volume until 1933, when it debuted its first Sears Christmas Book. This catalog included items for customers of all ages, but it showcased a higher-than-usual selection of children’s toys, from Lionel electric trains, to “Miss Pigtails” dolls, to Mickey Mouse watches. The Sears Christmas Book was an instant hit, and so many customers came to call it the “book of wishes” that in 1968 Sears formally renamed it the Wish Book.

By that time the percentage of Americans living in cities had more than doubled since Richard Sears had first issued his printed mailer (and suburban shopping malls and big-box stores like K-Mart were on the rise), but even as Americans urbanized they retained their affection for the convenience and charm of mail-order. In the winter of 1976 — the first year I possessed the skills to write down which gifts I wanted — the Sears Wish Book was, for me, inseparable from Christmas desire.

Re-Reading the 1976 Sears Wish Book: An Informal Exegesis

In 1943 Sears’ corporate newsletter boasted that the catalog served “as a mirror of our times, recording for future historians today’s desires, habits, customs, and mode of living.” Around this time Hollywood costume- and set-designers were beginning to use archived copies of the catalog to research styles and furnishings specific to certain eras — a show-business design strategy that was used throughout the twentieth century.

Indeed, the most striking feature of the 1976 Wish Book all these years later is the way it looks like an illustrated companion volume to That 70s Show. Corduroy, velour, and double-knit tartan-plaids abound. Pages 66-67 feature a variety of wide-collar polyester leisure suits for pre-school boys; pp. 90-91 feature Perma-Prest® gingham-and-lace dresses for preteen girls. Lava Lamps share a two-page spread with multi-function home disco-lights; four pages are devoted to beanbag-chairs. Barbie-doll enthusiasts could buy a “Discotheque” playhouse (“where fashion dolls come to rock-out”); TV-branded toys and sweatshirts featured images of Fonzie from Happy Days, J.J. from Good Times, and the “Sweathogs” from Welcome Back, Kotter. Sharp-eyed customers will note 22-year-old future supermodel Christie Brinkley donning nightgowns on pp. 6, 11, and 21 (future actress Renee Russo, also 22 at the time, sports a lime-green double-knit polyester dress on p. 130). Page 96 features long-since-forgotten “Sidecar Socks,” which were, essentially, knee-high tube socks with pockets sewn onto the shins.

Remembering the Ur-Pong/Pre-Walkman Era

The 1976 catalog also advertises two 8-track cassette players and one “portable monaural cassette player-recorder with AM/FM” — which is not particularly remarkable unless you go back one year and note that the 1975 catalog showcases six pages dedicated to 8-track players, and no AM/FM compact cassette players to speak of. What on the surface might have seemed like a simple technological shift hinted at a sea change in the way people were listening to (and interacting with) recorded music. The 1976 Sears “portable monaural cassette player-recorder” was, in fact, a kind of Ur-boombox that presaged mixtapes, hip-hop culture, and the general shift (embodied with the debut of the Walkman three years later) toward the average person being able to curate his or her own music in any environment.

Perhaps the most peculiar electronic items in the 1976 Wish Book were the four discrete “Tele-Game” consoles on pp. 390-391 — all of which featured variations of the video game Pong. Four decades on, when home video-game technology flirts with virtual reality (and rakes in more than $15 billion a year), it feels absurdly quaint that Sears would manufacture and sell different Pong consoles based on whether the game had one variation (Pong IV, $64.95), four variations (Super Pong IV, $98.95), or something in-between (Hockey Pong, $69.95; Super Pong, $78.95). Due to advances in circuit-chip technology since the silent TV-Pong games on offer in 1975, all four consoles boasted cutting-edge sound-effects. “You hear the action when the ‘ball’ hits,” the ’76 Wish Book exudes, “and when you score you hear a ‘beep’.”

Perhaps the most peculiar electronic items in the 1976 Wish Book were the four discrete “Tele-Game” consoles on pp. 390-391 — all of which featured variations of the video game Pong. Four decades on, when home video-game technology flirts with virtual reality (and rakes in more than $15 billion a year), it feels absurdly quaint that Sears would manufacture and sell different Pong consoles based on whether the game had one variation (Pong IV, $64.95), four variations (Super Pong IV, $98.95), or something in-between (Hockey Pong, $69.95; Super Pong, $78.95). Due to advances in circuit-chip technology since the silent TV-Pong games on offer in 1975, all four consoles boasted cutting-edge sound-effects. “You hear the action when the ‘ball’ hits,” the ’76 Wish Book exudes, “and when you score you hear a ‘beep’.”

What feels particularly telling amid the catalog’s 164 pages of children’s toys are items like the “Child’s Electric Sewing Machine” (“sew real clothes like Mom’s!”) on p. 558 of the girls’ section. This machine feels dated less because of advances in gender politics than for the fact that, over the course of the next decade, inexpensive Asian-made clothing pretty much precluded the need for sewing machines in middle-class households. In 1976, when China’s anti-capitalist Cultural Revolution was (along with Mao Zedong) in its death-throes, American women like my mother commonly purchased “dress patterns” and sewed their own clothes. By the end of the 1980s, however, Chinese-made clothing was so cheap (and ubiquitous) at big-box retailers that sewing ceased to be a necessary skill for young people.

Remembering the Post-Vietnam/Pre-Star Wars Era

Just as tellingly, the 1976 Wish Book is also a relic of final era before Star Wars (which hit cinema screens the following spring) revolutionized the way toys were marketed to young people. Apart from a few items branded to Happy Days, the Bionic Woman, and Star Trek (including obvious Star Trek rip-off gadgets like the “Beyond Tomorrow Lunar Space Station”), few of the toys are pegged to movies or TV. Established war-toy lines like G.I. Joe had fallen out of favor in the wake of the Vietnam War, and the only military gadgets in the ’76 catalog refer either to long-bygone conflicts (like the Matchbox “World War II” miniatures on p. 447) or non-weaponized vehicles (like the G.I. Joe gliders and jeeps on p. 467).

As the popularity of military tie-ins waned, toy companies launched action-figure lines like Big Jim’s P.A.C.K. (short for “Professional Agents and Crime Killers,” a multi-ethnic, A-Team-like band of secret agents) and J.J. Armes, a “Super Private Eye” doll whose Bio-Kinetic™ hands could be replaced with hooks, magnets, or suction cups. Like Evel Knievel (whose stunt-motorcycle toys featured on p. 442), J.J. Armes was a real-life person — an El Paso-based private detective who’d lost his hands in a childhood railroad accident and plied his trade with a pair of prosthetic hooks. Armes was best known for rescuing Marlon Brando’s son Christian from Mexico-based kidnappers in 1972, and a few years later the TV success of the Six Million Dollar Man had compelled Ideal Toy Company to create an action figure in his image. This toy hit the market in tandem with a ghostwritten autobiography entitled Jay J. Armes: Investigator — but the would-be super-hero’s rise to fame was derailed by an incisive (and uncomfortably hilarious) 1976 Texas Monthly article that depicted the amputee detective as a fabulist nitwit with a cartoonishly exaggerated sense of his own talents.

As the popularity of military tie-ins waned, toy companies launched action-figure lines like Big Jim’s P.A.C.K. (short for “Professional Agents and Crime Killers,” a multi-ethnic, A-Team-like band of secret agents) and J.J. Armes, a “Super Private Eye” doll whose Bio-Kinetic™ hands could be replaced with hooks, magnets, or suction cups. Like Evel Knievel (whose stunt-motorcycle toys featured on p. 442), J.J. Armes was a real-life person — an El Paso-based private detective who’d lost his hands in a childhood railroad accident and plied his trade with a pair of prosthetic hooks. Armes was best known for rescuing Marlon Brando’s son Christian from Mexico-based kidnappers in 1972, and a few years later the TV success of the Six Million Dollar Man had compelled Ideal Toy Company to create an action figure in his image. This toy hit the market in tandem with a ghostwritten autobiography entitled Jay J. Armes: Investigator — but the would-be super-hero’s rise to fame was derailed by an incisive (and uncomfortably hilarious) 1976 Texas Monthly article that depicted the amputee detective as a fabulist nitwit with a cartoonishly exaggerated sense of his own talents.

I have only the vaguest memories of J.J. Armes and Big Jim’s P.A.C.K., since at age six, the focus of my Christmas-wish obsession was football. At the time, the National Football League had aggressively branded itself in the Sears catalog, from NFL pajamas ($6.99), to NFL belt buckles ($2.00), to NFL bedsheets ($17.96), to NFL play helmets ($8.99), to NFL electric football sets ($15.97), a pre-video-game curiosity that featured football-player figurines rattling their way across a vibrating metal game-board. The 1976 Sears Wish Book seemed to imply that professional football was the only significant spectator sport in America, and apart from a brief inventory of Major League Baseball-team wristwatches (listed beneath larger photos of NFL-team watches on p. 215), there’s no evidence that other American pro-sports leagues existed.

If Sears Wish Book licensing was a calculated promotion strategy on the part of the NFL, it was a brilliant one. In the mid-1970s professional football was growing in popularity, but the average player still made less than $40,000 a year, and baseball was inarguably America’s premier sport. Two decades later pro football had become statistically more popular than pro baseball, in part because of the NFL’s adoption of more viewer-friendly rules (and fan bitterness over the strike-canceled 1994 MLB season) — but I can’t help but think it also had something to do with the way the Sears Wish Book seeded NFL-branded desire in the minds of little boys like me.

If Sears Wish Book licensing was a calculated promotion strategy on the part of the NFL, it was a brilliant one. In the mid-1970s professional football was growing in popularity, but the average player still made less than $40,000 a year, and baseball was inarguably America’s premier sport. Two decades later pro football had become statistically more popular than pro baseball, in part because of the NFL’s adoption of more viewer-friendly rules (and fan bitterness over the strike-canceled 1994 MLB season) — but I can’t help but think it also had something to do with the way the Sears Wish Book seeded NFL-branded desire in the minds of little boys like me.

Indeed, I’ve always wondered why I loved football so much when I was that age. My teenaged uncle had been a high school football star, and I’d enjoyed watching the NFL on TV each Sunday, but when it came to regional sports teams I got far more excited watching baseball’s Kansas City Royals (who were very good at the time) than football’s Kansas City Chiefs (who were not). It very well could be that I didn’t savor the Sears Wish Book because I loved the NFL so much as I loved the NFL because I savored the Sears Wish Book.

Until I started writing this, that possibility hadn’t even occurred to me; now, when I think about it, it feels obvious.

The Leaves of Grass of Late-Twentieth-Century Commerce

Sears published its last general-interest mail-order catalog in 1993, and began to scale back its Christmas Wish Book around the same time. By 2005 the Wish Book had been effectively discontinued, and while Sears has maintained an online version at WishBook.com since 1998, it in no way evokes the self-contained wonder of the old holiday mail-order book. A new generation of Americans — pretty much anyone born after the mid-1980s — has little idea what the Sears Wish Book was, let alone what it represented to young readers for most of the twentieth century.

Taken as literature, the Wish Book was more than a fictive vessel for childhood reverie; it was, in practice, a democratizing document that unmoored its readers from the constraints of place and tradition, uniting them in an optimistic narrative of cosmopolitan middle-class aspiration. This is, I think, an under-appreciated aspect of American commercial literature. One of the reasons U.S. newspapers were able to sidestep European-style partisan patronage more than a century ago, for instance, was that revenue from retail-store advertisements allowed them to stay politically neutral. In a similar way, the Sears catalog, with its mail-order objectivity, regarded all potential customers as equals by way of their purchasing power.

One detail of the 1976 Wish Book that caught my attention upon rereading it was the matter-of-fact inclusion of black faces among its fashion models. Of the catalog’s 269 clothing-oriented pages, African-Americans appeared on 30 them, which — at 11.1 percent — was the exact demographic sample-size of African-Americans nationwide in the mid-1970s. That can’t have been an accident, any more than it was an accident when the 1904 catalog’s hair-care section added wigs for African-Americans in tandem with the emergence of the black bourgeoisie. (Asian-Americans are noticeably scarce in the 1976 Wish Book, but by the mid-1980s — after a decade of ramped-up immigration and demographic purchasing power — Asian faces were appearing in proportion to their population sample.)

What It Means When a Kid Wishes For Something

As a writer I’m best known for a book that promotes (among other things) lifestyle simplicity and anti-consumerist restraint — values which would seem to be at odds with my childhood Wish Book fixation. It’s worth noting, however, that my book’s philosophy is pragmatic (rather than ideological) in nature. There is, after all, a difference between mindless consumption and simple longing, and the Wish Book was never a prescription for unfettered accumulation so much as it was a Whitmanesque index of possibility.

Much as other works of twentieth-century literature explored themes of knowledge versus ignorance, man versus nature, and individual versus society, the Sears Wish Book ultimately transported its reader into the inevitable disconnect between anticipation and reality. As often as not, the childish yearning for Christmas morning was more enchanting than the occasion itself, and the act of unwrapping that soon-to-be-dated Super Pong IV console (or, in my case, a not-exactly-wished for Wide World of Sports wastebasket) carried as much emotional resonance as the subsequent hours spent using it. In learning to appreciate this line between promise and actuality, the young Wish Book reader was sharpening his instincts for life in general.

Note: I don’t host a “comments” section, but I’m happy to hear your thoughts via my Contact page. To learn more about what this blog is all about, read items #2 and #3 from my recent update post.