On the pleasures and paranoia of being a mostly clueless white guy in the company of Third World hosts.

By Rolf Potts

I am 15 minutes into my hike down the muddy little stream when a tree carving captures my attention. Sticky with sap and arcing brown across the bark, it seems to have been made recently.

I drop to my haunches and run my fingers over the design. After three days of living on the Indochinese outback without electricity or running water, I feel like my senses have been sharpened to the details of the landscape. I take a step back for perspective, and my mind suddenly goes blank.

The carving is a crude depiction of a skull and crossbones.

Were I anyplace else in the world, I might be able to write off the skull and crossbones as a morbid adolescent prank. Unfortunately, since I am in northwestern Cambodia, the ghoulish symbol can mean only one thing: land mines. Suddenly convinced that everything in my immediate vicinity is about to erupt into a fury of fire and shrapnel, I freeze.

My brain slowly starts to track again, but I can’t pinpoint a plan of action. If this were a tornado, I’d prone myself in a low-lying area. Were this an earthquake, I’d run to an open space away from trees and buildings. Were this a hurricane, I’d pack up my worldly possessions and drive to South Dakota. But since I am in a manmade disaster zone, all I can think to do is nothing.

My thoughts drift to a random quote from a United Nations official a few years back, who was expressing his frustration in trying to clear the Cambodian countryside of hundreds of thousands of unmarked and unmapped mines. “Cambodia’s mines will be cleared,” he’d quipped fatalistically, “by people walking on them.”

As gingerly as possible, I lower myself to the ground, resolved to sit here until I can formulate a course of action that won’t result in blowing myself up.

* * *

For the past decade, northwestern Cambodia has been home primarily to subsistence farmers, U.N. de-mining experts and holdout factions of the genocidal Khmer Rouge army. Except for travelers headed overland from the Thai border to the monuments of Angkor Wat, nobody ever visits this part of the country.

If someone were to walk up right now and ask me why I’m here, who I’m staying with and how I got to this corner of the Cambodian boondocks, I could tell them truthfully that I do not exactly know.

Technically, I was invited to come here by Boon, a friendly young Cambodian who shared a train seat with me from Bangkok to the border three days ago. Our third seatmate, a Thai guy who called himself Jay, knew enough English for the three of us to exchange a few pleasantries along the way. Our conversation never amounted to much, but as we got off the train at the Thai border town of Aranyaprathet, Boon asked through Jay if I was interested in staying with him and his family once we got to Cambodia. Eager to explore a part of Cambodia that was a notorious Khmer Rouge stronghold only six months ago, I accepted.

Jay parted ways with us at the train station, and that was the last time I had any real clue as to what was going on.

Perhaps if I hadn’t forgotten my Southeast Asian phrasebook in Bangkok, I would have a better idea of what was happening. Unfortunately, due to a moment of hurried absent-mindedness shortly before my departure to Aranyaprathet, I left my phrasebook languishing on top of a toilet-paper dispenser in the Bangkok train station. Thus, my communication with Boon has been limited to a few words of Lao (which has many phrases in common with Thai, Boon’s second language) that I still remember from a recent journey down the Laotian Mekong.

My Lonely Planet: Southeast Asia guide also provides a handful of Khmer words; unfortunately, phrases like “I want a room with a bathtub” and “I’m allergic to penicillin” only go so far when your hosts live in a one-room house without running water.

As a result, trying to understand the events of the last three days has been like trying to appreciate a Bengali sitcom: I can figure out the basics of what’s going on, but most everything else is lost in a haze of unfamiliar context and language. In a way, this is kind of nice, since I have no social expectations here. Whereas in an American home I would feel obligated to maintain a certain level of conversation and decorum, here I can wander off and flop into a hammock at any given moment, and my hosts will just laugh and go back to whatever it was they were doing. At times I feel more like a shipwrecked sailor than a personal guest.

The majority of my stay here in Cambodia has been at Boon’s mother’s house, in a country village called Opasat. Boon’s wife and baby daughter also live here, as well as a half-dozen other people of varying age, whose relation to Boon I have not yet figured out.

My first morning in Opasat, Boon took me around and introduced me to almost everyone in his neighborhood. I don’t remember a single name or nuance from the experience — but everyone remembers me because I kept banging my head on the bottom of people’s houses, which stand on stilts about six feet off the ground. Now I can’t walk from Boon’s house to the town center without someone seizing me by the arm and dragging me over to show some new relative how I’m tall enough to brain myself on their bungalow.

* * *

After five minutes of paranoid inaction in front of the skull and crossbones tree, I hear the sounds of children’s voices coming my way. I look up to see a half-dozen little sun-browned village kids strung out along the stream bank. Suddenly concerned for their safety, I leap to my feet and try to wave them off.

Unfortunately, my gesticulations only make the kids break into a dead sprint in my direction. I realize that the kids think I am playing a game I invented yesterday, called “Karate Man.”

The rules behind Karate Man are simple: I stand in one spot looking scary, and as many kids as possible run up and try to tackle me. If the kids can’t budge me after a few seconds, I begin to peel them off my legs and toss them aside, bellowing (in my best cartoon villain voice) “I am Karate Man! Nobody can stop Karate Man!” Caught up in the exaggerated silliness of the game, the kids tumble and backpedal their way 20 or so feet across the dirt when I throw them off. Then they come back for more. It’s a fun way to pass the time, and it’s much less awkward than trying to talk to the adults.

At this moment, however, I’m in no mood to be surrounded by a field of exploding Cambodian children. “No!” I yell desperately. “No Karate Man!”

“Kanati-maan!” the kids shriek back, never breaking stride.

As the kids charge me, I clutch them to me one by one, and we sink to the ground in a heap. Convinced that they have just vanquished Karate Man, the children break into a cheer.

I stand them up, dust them off, then make them march me back the way they came. Thinking this is part of the game, the kids take the task very seriously. We walk in single file, the kids doing their best to mimic my sober demeanor. Nobody blows up. By the time the buildings of the village are in view, I begin to relax again.

Once I arrive back at Boon’s house, one of the kids is immediately dispatched for a sarong. This, I have learned, is the signal that it’s time for me to take a bath. I’ve already bathed once today, but my hosts seem to think it’s time for me to bathe again. This could have something to do with the fact that I’m sweaty and dusty from the hike, but I suspect that my hosts just want an excuse to watch me take my clothes off.

Since there is no running water at Boon’s house, all the bathing and washing is done by a small pond out back. The first time I was hustled out to take a bath, I didn’t realize that it would be such a social undertaking. By the time I’d stripped down to my shorts, a crowd of about ten people had gathered to watch me. Since I’d never paid much attention to how country folks bathe in this part of the world, I wasn’t quite sure what to do next. I figured it would be a bad idea to strip completely naked, so I waded into the pond in my shorts. A gleeful roar went up from the peanut gallery, and a couple of kids ran down to pull me out of the murky water.

In the time since then, I have learned that I am supposed to wrap a sarong around my waist for modesty, and bring buckets of water up from the pond to bathe. Since I have very white skin, my Cambodian friends watch this ritual with great curiosity. My most enthusiastic fan is a wrinkled old neighbor woman who is given to poking and prodding me with a sense of primatological fascination that would rival Jane Goodall. When Boon took me over to visit her house two mornings ago, she sat me down on her porch, yanked off my sandals, and pulled on my toes and stroked my legs for about five minutes. At first I thought she was some sort of massage therapist, until she showed up at my bath this morning and started pulling at the hair on my nipples.

This afternoon, Old Lady Goodall manages to outdo herself. As I am toweling off under a tree, she strides up and starts to run her fingers over my chest and shoulders, like I’m some sort of sacred statue from Angkor Wat. If this woman were 40 years younger and had a few more teeth, it might be a rather erotic experience; instead, it’s just kind of strange. Then, without warning, Madame Goodall leans in and licks the soft white flesh above my hipbone. Comically, furrowing her brow, she turns and makes a wisecrack to Boon’s mother, who erupts into laughter.

I can only assume this means I’m not quite as tasty as she’d expected.

* * *

By nightfall, I know something is amiss. Usually, my hosts have prepared and served dinner by early evening, and we have cleaned up and are playing with the baby (the primary form of nighttime entertainment, since there are no electric lights) by dark. But this evening there is no mention of dinner, and a group of a dozen young men from the neighborhood have gathered at Boon’s place. They gesture at me and laugh, talking in loud voices. I laugh along with them, but as usual I have no idea what’s going on. For all I know they’re discussing different ways to marinate my liver.

About an hour after sundown, Boon indicates that it’s time to go. I get up to leave, but I can’t find my sandals. After a bit of sign language, a search party is formed. Since my size-13 sandals are about twice as big as any other footwear in the village, it doesn’t take long to track them down. One of the neighbors, a white-haired old man who Boon introduces as Mr. Cham, has been flopping around in my Tevas. Mr. Cham looks to be about 60, and he’s wearing a black Bon Jovi T-shirt. When Boon tells him that he has to give me my sandals back, Mr. Cham looks as if he might burst into tears.

Finally ready, I hike to the village wat with Boon and the other young men. The wat is filled with revelers, and has all the trappings of an American country fair. Dunk tanks and dart-tosses are set up all along the perimeter, and concession tables selling cola, beer, noodle soup and fresh fruit dot the courtyard. A fenced-in dancing ring has been constructed around the tallest tree in the wat, and a sound system blasts traditional and disco dance tunes.

Boon nods at me and sweeps his hand at the courtyard. “Chaul Chnam,” he says. “Khmer Songkhran.”

Songkhran is the Thai New Year celebration, so I gather that Chaul Chnam marks the Khmer New Year. As with Thai kids at Songkhran, Cambodian children run roughshod over the Chaul Chnam celebration, throwing buckets of water and pasting each others’ faces with white chalk powder.

I suspect that Boon’s young male friends have brought me to Chaul Chnam so they can use me to meet girls, but I am surrounded by little kids before we have a chance to do any tomcatting. Apparently, my reputation as Karate Man has spread, and now I can’t walk anywhere without a gaggle of Cambodian kids trying to tackle me. Not up for a night of getting mobbed like a rock star (or, more accurately, a cast member of “Sesame Street Live”), I manage to neutralize the children by shaking hands with them in the manner of a charismatic politician. Since I can only shake hands with one kid at a time, this slows things down a bit.

Boon ultimately rescues me by taking me to a folding table, where he introduces me to a fierce-looking man called Mr. Song. Mr. Song has opted not to wear a shirt to the Chaul Chnam festivities; his chest is laced with indigo tattoos and his arms are roped with taut muscles. He looks to be in his 40s, which inevitably means that he has seen some guerrilla combat over the years. Given our location, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if he served his time in Khmer Rouge ranks. When I buy the first round of Tiger lager, Mr. Song is my buddy for the rest of the evening.

Although I am tempted to jump into the dance ring and take a shot at doing the graceful Khmer aspara, I end up holding court at the table for the next three hours. When Boon leaves to dance with his wife, Mr. Song becomes master of ceremonies, introducing me to each person that walks by the table. Everyone I meet tries to make a sincere personal impression, but it’s impossible to know what anyone is trying to communicate. One man pulls out a faded color photograph of a middle-aged Cambodian couple decked out in 1980s American casual-wear. The back of the photo reads: “Apple Valley, California.” Another man spends 20 minutes trying to teach me how to count to 10 in Khmer. Each time I attempt to show off my new linguistic skills, I can’t get past five before everyone is doubled-over laughing at my pronunciation.

It comes as a kind of relief when the generator suddenly breaks down, cutting off the music in mid-beat and leaving the wat dark.

On the way back to the neighborhood, Boon pantomimes that Mr. Song wants me to sleep with his family. Once we arrive at his house, Mr. Song lights some oil lamps, drags out an automobile battery and hooks it up to a Sony boom box. After a few minutes of tuning, we listen to a faint Muzak rendering of “El Condor Pasa” on a Thai radio station. This quickly bores Mr. Song, and he walks over to the corner and puts the radio away.

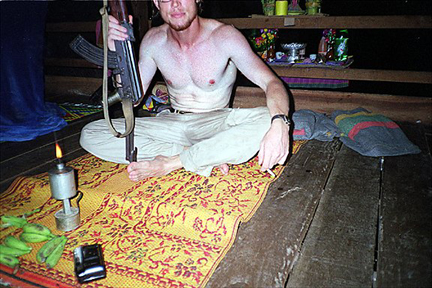

He returns carrying a pair of AK-47 assault rifles and four banana clips of ammunition. Motioning me over, he sits on the floor and begins to show me how the guns work. Three of the clips, he indicates, have a 30-round capacity, and the fourth holds 40 bullets. In what I assume is a gesture of hospitality, Mr. Song jams the 40-round clip into one of the rifles and hands it to me. I get a quick lesson on how to prime the first round, and how to switch the rifle to full automatic fire.

Mr. Song doesn’t appear to realize that this is a doomed enterprise. Unless we are attacked tonight by Martians, or intruders who wear crisp white T-shirts that read SHOOT ME, I won’t have the slightest idea how to distinguish a bandit from a neighbor. For good measure — and not wanting to sully his macho mood — I hand Mr. Song my camera, and indicate that I want him to take a picture of me with the AK-47. From the way he holds my camera, I can only conclude that this is the first photo he’s ever taken.

When I finally fall asleep, I dream that I am renting videos from a convenience store in outer space.

* * *

Not wanting to overstay my welcome, and largely exhausted by my local-celebrity status, I tell Boon of my intention to leave Opasat the following morning. Boon indicates that he understands, and sends for a motorcycle taxi to take me to the overland-truck depot in the city of Sisophon.

To show my appreciation for all the hospitality, I give Boon’s mother a $20 bill — figuring that she will know how to split it up among deserving parties. As soon as the money leaves my hand, I see Mr. Cham run off toward his house. When he returns, he is carrying a travel bag, and he’s traded his Bon Jovi shirt for a purple polo top and a brown porkpie hat. Boon confers with him for a moment, then apologetically indicates that Mr. Cham wants me to take him from Sisophon to Angkor Wat. Not wanting to seem ungrateful, I shrug my consent.

When the motorcycle taxi arrives, I make my rounds and say my goodbyes. I save Boon for last. “Thanks, Boon,” I say in English. “I wish I could tell you how much I appreciate all this.” He can’t understand me, of course, but he returns my pleasantry by bringing his hands together in a traditional Khmer bow. I give him a hug, knowing that I will probably never know why he invited me to come and see his family, or even what he does for a living.

I get onto the motorcycle between the driver and the eccentric Mr. Cham, and we take off in a flourish of dust. Opasat disappears behind me in a matter of minutes, and my thoughts move on to the sundry details of finding an overland truck and fulfilling my tourist agenda at Angkor Wat.

I am still not exactly sure what has just happened to me, but I know that I rather enjoyed it.

This will not stop me, however, from buying a new phrasebook the moment I see one for sale.

This essay originally appeared in Salon.