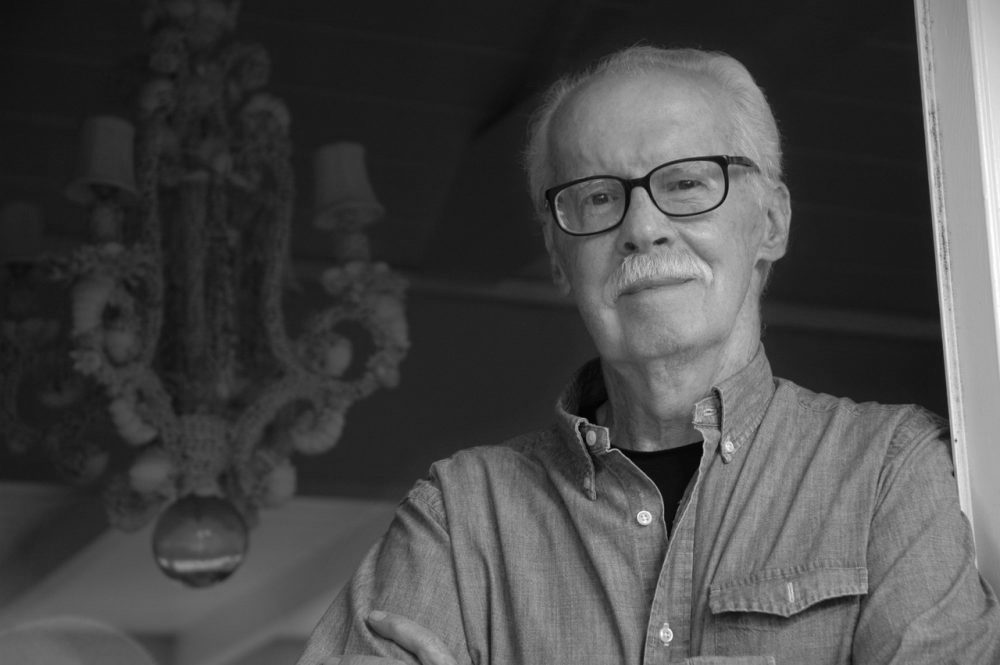

By Michael Mewshaw

First presented as the plenary address at the 2004 South Central MLA Conference in New Orleans, October 28, 2004

(an excerpt)

I’ve traveled here to New Orleans from London, where I spend part of each year. And most of you have traveled some distance from your homes and universities so that I can lecture and you can listen to a lecture about travel writing. At first blush this might seem a dubious topic, or at any rate a lightweight one for a Modern Language Association meeting. But in the course of the coming hour I hope to persuade you that travel, far from being a frivolous diversion best left to the yokels on Bourbon St. with their ball caps, beer cans and zany tee shirts, is in literary terms a crucial act.

First, of course, we must define our terms! According to some critics and cavilers, travel no longer exists. It’s all been replaced by the plague of tourism. And tourism, we’ll have to concede, ranks just below racism or pedophilia on the Politically Incorrect Index. We may do it but we don’t like to admit it. We would all prefer to be authentic travelers, not tourists, if only we could.

But it is my contention — and one of my themes tonight — that travel in the traditional sense is still possible and moreover, it is important for writers and thus to readers. Just as religious faith has lingered on long after the alleged death of God, and just as writers have continued to produce novels long after the much-discussed demise of that genre, people still do scuttle around the globe, reenacting rituals that were supposed to have died off ages ago. At the most basic level, they do so, it seems to me, in order to enjoy what poet Wallace Stevens called the pleasures of “merely circulating.” Perhaps because immobility reminds us of that ultimate fact of life — i.e. Death — we remain eager to prove we’re still alive by moving around and rubbing up against our fellow travelers. Seen objectively, many of us appear to have been hard-wired to follow migratory patterns that lead not just to a destination but to a condition in which “discovery” remains a potential reality even in places where masses of human beings have proceeded us.

The good doctor Freud speculated that “a great part of the pleasure of travel lies in the fulfillment of these early wishes to escape the family and especially the father.” In that sense, travel may be viewed as a rebellious, even a subversive act, part of the process of self-actualization I travel to define and assert my existential identity. I travel. Therefore I am.

In his thoughtful and enjoyable book Abroad, Paul Fussell discusses travel and travel literature between World War I and World War II. Focusing primarily on the British experience, he observes that the Great War forced most people to stay home, or to stay put where the army sent them and this caused damaging consequences for English arts and letters, not to mention for the population at large. Without travel, Fussell claims, there’s inevitably “a loss of amplitude, a decay of imagination and intellectual possibility corresponding to the literal loss of physical freedom.” Writers, it would appear, need travel, its freedom, its stimulation and exposure to new and innovative points of view in the same way they need air, editors and a reading audience.

And the rest of us, whether we realize it consciously also crave both what travel is and what it represents. Those who doubt this might do well to recall how many totalitarian regimes outlaw travel or restrict it to the privileged elite — all in an effort to control the citizenry, keep folks ignorant of what’s happening and what people are like in other parts of the world. Historically, by circumscribing freedom of movement, tyrants have sought to reinforce the belief that the homeland is holy ground, and foreign lands and people are beyond the pale, if not downright satanic.

More than 75 years ago Robert Byron, author of The Road To Oxiana, regarded by most critics as the greatest travel book in the English language, conjectured that the excesses and failures of British colonialism were due to “insufficient, or insufficiently imaginative, travel.” In an aside, with some reluctance to stray from literature to politics, I wonder whether the same might be said about the United States’s problems in the Middle East and Central Asia. Could they be due, at least in part, to a general ignorance of those places and people, and their customs, culture and religion? Please don’t take this as a partisan statement. There’s plenty of blame to go around. To hear our President refer to great stretches of the world as an Axis of Evil may make some of us gnash our teeth. But at the other end of the political spectrum, there are men whose judgments should also make us cringe. I remember Dan Rather, early in the war in Afghanistan, referring to the Northern Alliance as “fiercely independent and freedom-loving people.” But having traveled in that part of the world myself, I’m here to tell you that our allies in the Northern Alliance, just like many of our other allies in Afghanistan, are essentially warlords, drug dealers and thugs. Years before our own attention turned to Afghanistan, the Northern Alliance had taken over in Kabul, with catastrophic consequences for its inhabitants. The Taliban, by contrast, were seen at first as serious reformers, even saviors, and they drove the Northern Alliance into a single remote valley in the far northeast of the country. Clinging to the illusion that the enemy of my enemy is necessarily my friend, the United States breathed life back into the Northern Alliance, along with many other warlords, and welcomed them into its campaign against the Taliban and Al Queda. Now we have no way to curb the excesses of our dubious brothers in arms.

But enough about geo-politics, my opinions, and for the moment about my experiences in Central Asia. I’ll come back to the latter. First I’d like to return to Paul Fussell who writes in Abroad that: “Travel is work. Etymologically, a traveler is one who suffers travail, a word deriving in its turn from Latin tripalium, a torture instrument consisting of three stakes designed to rack the body. Before the development of tourism, travel was conceived to be like study, and its fruits were considered to be the adornment of the mind and the formation of judgment.” Surely something of this still applies. Think of all those college students doing their junior years abroad. Think of backpackers taking a gap year to traipse around Southeast Asia. Think of the doughty ladies and gents who sign up for Lindblad tours to Antarctica or the Galapagos. In large measure, they’re traveling to learn, to grow, to bring back badges of their newfound knowledge. Much the same holds true for writers of fiction as well as non-fiction. For them the open road is both a classroom and an escape, an attempt to outflank the empty page and an effort to explore the unfathomable.

True, there are less uplifting examples of travel. There’s always been a sort of anti-travel in which people don’t so much go anywhere as simply take their prejudices and presuppositions out for a drive. And there is a kind of travel writing which is really guide book writing which focuses on what the trade calls “service” and which consists mostly of recording whether the sheets in a hotel were crisp or the lettuce in a restaurant was limp But that’s not the kind of travel or travel writing I’m talking about today. No, I am trying to make a case that travel in the classic mode still exists and that the best travel writing is a significant form of literature. What’s more, I’d like to suggest that travel is the basic underpinning or subtext of a lot of literature which we wouldn’t normally associate with travel.

Just last month, while driving from Paris to Venice, I happened upon the September issue of Harper’s magazine which bears directly on this issue. Written by Nicholas Delbanco, the piece was entitled “Anywhere Out of This World: On Why All Writing is Travel Writing.” Delbanco makes a persuasive, or at least a provocative case, when he argues that “In the Western tradition of literature, the common denominator of the Odyssey and Pilgrim’s Progress, the Canterbury Tales and The Divine Comedy— not to mention Don Quixote and Moby Dick or Faust — is near-constant motion.” The most enduring books, he contends, are exploratory. They are quests that introduce readers to unprecedented events and insights, to a world of wonders, to what Ezra Pound called “news that stays news.” The greatest authors are in a loose sense all travel writers; they maintain I’ve been there, I witnessed it and have come back to tell the tale,

Years earlier as if anticipating Delbanco, Paul Fussell pointed out intriguing ways that literature and travel have always been intimately implicated with each other. He observes that even the language of travel and of literary criticism overlap. In both cases we speak of setting out, starting off, making transitions, taking detours or digressions, doubling back and approaching events or destinations from different points of view. Then, too, we measure distances in kilometers, just as we speak of a line of poetry’s meter, and we often hear scholars discuss texts in terms that remind us of landscape descriptions. They talk of rising action, narrative bridges, dramatic arcs, character delineation and so forth.

Finally, where Delbanco observes that all writing is travel writing, Fussell takes pains to demonstrate how specific pieces of the best travel writing bear the hallmarks of particular literary genres. For example they have much in common with the picaresque tale and personal memoirs. In an especially fascinating exegesis of Byron’s Road To Oxiana, he hails the book as “the wasteland” of travel writing, for like Eliot, Byron constructed his book out of fragments of conversation, literary allusions and quotes, Homeric lists, etc.

Now I hope I won’t sound like an ingrate if after citing Fussell and Delbanco for support when it suits me, I turn around and take issue with them. But both men side with the heretics who maintain that true travel no longer exists. Delbanco writes that the death of Wilfred Thesiger rang “a kind of knell for the solitary wanderers,” — for travel as travail and exploration. But 15 years ago I irritated Mr. Thesiger and a lot of his admirers when I faulted his autobiography, The Life of My Choice, in The New York Times for misrepresenting and melodramatizing his experiences. Like many of the most famous voyagers of the 19th and 20th centuries, Thesiger, in fact seldom traveled alone. He just wrote in an egocentric manner that promulgated the false impression that he was an isolated individual wandering through the empty wilderness, plugging along with limited resources, buoyed up only by his personal courage and staunch resolve. But in fact, Thesiger was supported financially by a horde of wealthy patrons and by the Royal Geographic Society. More crucially, he was often accompanied and protected by hundreds of troops of the British army. None of his expeditions took him through uncharted or uninhabited territory. He never discovered a place. He merely visited people who had long lived where he chose to travel, And some of his most celebrated journeys in Somalia and Abyssinia would never have succeeded if he hadn’t requisitioned — i.e. stolen — supplies from local villages, demanded shelter at gunpoint and press-ganged hundreds of natives into serving as bearers, scouts and bodyguards. That that type of travel is no longer possible is, in my opinion, not to be regretted, but rather celebrated along with the end of other manifestations of blatant racism and colonialism.

While lamenting the passage of heroic explorers, Fussell also decries what he imagines to be the homogenization of the world, the way in which whole cities and previously remote regions have become interchangeable and safe for Mom and Dad and Buddy and Sis, He argues that airport design has become a “ubiquitous international idiom.” He jokes that “the closest one could approach an experience of travel in the old sense today would be to drive in an aged automobile with doubtful tires through Romania or Afghanistan without hotel reservations and to get by on terrible French.”

To which I can only reply, Mr. Fussell really should get out more. As I learned last winter, Bangkok may be as crowded, polluted and as unalluring as Lefrak City, but parts of Thailand are as untouched and as lawless, I might add, as the Empty Quarter. In Cambodia I was distressed to see that Siem Reap, the satellite city to Angkor Wat, now boasts hotels that remind one of a miniature Las Vegas, but a short walk in any direction brings one into touch with a life that hasn’t changed much in centuries. Or a short walk down the wrong path in Angkor Wat leads to death — as many areas are still seeded with mines left by the Khmer Rouge. When in Laos, at the former capital of Luang Prabang, I luxuriated in a five-star hotel and luxuriated in the lovely ironies all around me — saffron-robed monks in Internet cafes, Australian backpackers who are known locally as Minky Tow, literally turtle shit, because of their unhygienic habits. There’s the garage at the former royal palace which proudly displays two Ford Edsels and a 15 ft. speedboat with an Evenrude outboard engine, all gifts of the USA. But when I tried to catch a bus to the new capital of Vientiane, I found out that service had been suspended because bandits had closed the road. Weeks earlier they had robbed and killed a busload of travelers. Suddenly I realized maybe Mistah Kurtz ain’t dead after all, and that a few miles from the poshest hotel there’s still enough horror for any writer to contemplate and any reader to be troubled and challenged by.

There are no-go areas and unexplored patches in even well-mapped European metropolises. In Valencia, Spain, I recently learned, there is a neighborhood populated almost entirely by African immigrants that has been put off-limits to the police, the post office and other municipal services. The Spanish government has simply declared it to be too dangerous. In short, it’s a place that would need Burton and Speke to explore and analyze.

Whole nations in Africa, and Latin and South America fall into the same category. They are largely unknown, seldom visited, extraordinarily uncomfortable and every bit as threatening as the Danikil Desert was when Wilfred Thesiger crossed it in the 1930s. Airplanes, CNN, and the Internet may offer the illusion that nowhere in the world is unreachable, unexplored or unexamined. Yet for ten years Algeria might have been the dark side of the moon, and the savagery between an unelected government and Islamic terrorists turned that country into a Heart of Darkness in which tens of thousands of people were killed just an hour’s flight from Rome or Nice.

Were Graham Greene still alive, he would find Liberia as alien and uncharted — and far more hostile than it was when he went there and wrote Journey Without Maps. And if he returned to Chiapas province in Mexico he might not be mistaken for assuming that little has changed since he wrote The Lawless Roads. Naked kids with pot bellies, malnourished and malarial adults, a tense violent stand-off between Indians and the army, and the sort of moral ambiguity that have become the hallmarks of Greenland. Although for different reasons, and despite new technology — or perhaps because of it — these places are more unstable than ever. And I should emphasize more than ever crying out to be visited by and written about by novelists of Greene’s courage, capacity for outrage and ferocious truth telling.

And as for airports all being the same, I wonder whether Fussell has ever flown, as I have in recent years, into Dar Es Salaam or Zanzibar or Tashkent.

I sense, and perhaps you do, too, a tone of special pleading and personal self-interest taking over this otherwise utterly objective academic discourse. I should have confessed early on that it’s difficult for me to adopt a detached position on travel and travel writing and its relationship to literature. After all, I started my so-called career with a novel, Man In Motion, which took as its epigraph lines from T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding.”

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started.

And know the place for the first time.”

Man In Motion was a picaresque tale about a driving trip across the US and down into jungles of Mexico. In the era of Easy Rider, I guess you could say it was an anti-road novel. But it certainly didn’t persuade me to stay at home. Instead, I hit the road myself and over the past 34 years I have lived in France, Italy, Spain, Morocco and England, have traveled from one end of Africa to the other, have spent time in a dozen Islamic countries, have drifted around the former Soviet Bloc and Central Asia, and have even put in a few years in Texas, one of the most exotic, remote, culturally fascinating and confusing places I’ve ever visited. I also consider it to be my greatest honor to have been made a member of that oxymoronic literary organization — the Texas Institute of Letters.

Along with photographs, frequent flier miles, various diseases, unpleasant hospital experiences and memorable encounters with local law enforcement, one salient result of all this travel has been 16 books, many of them directly connected to my itinerary.

Now at the age of 61 I’m still on the move, still don’t own a house or furniture and never spend more than a few months in any one spot. Motion, travel, distant settings, deracination and alienation remain major themes in my fiction. Then, too, in the past twenty years I’ve written a few hundred articles that deal with foreign places. I wouldn’t call these travel pieces in the conventional sense. They certainly don’t have much in the way of service. Instead, they attempt to evoke a place and to show a narrator — i.e. me — passing through new settings and experiences. Almost always told in the first person, they employ a host of fictional devices — dialogue, dramatic scenes, comic incidents and irony. Which makes sense in that I construed them as short story substitutes. When the market for short fiction had shrunk to insignificance, I decided to stop writing stories for literary magazines that paid little or nothing and were read by few people or nobody. Instead I wrote for magazines and newspapers that sent me to interesting places, picked up the bills and left me free to recycle the experiences into my fiction.

So, yes, this subject is near and dear to me and is absolutely integral to my work. Despite my minor caveats about Delbanco and Fussell, I would agree with them in the main. All writing is travel writing — even if the journey is entirely inward through the obscure bends and elbows of the mind, or even if it’s an intimate exploration of a body. As D.H. Lawrence once told Bertrand Russell, “The greatest living experience for every man is his adventure into the woman.”

I would also agree with Mark Shorer who said of D.H. Lawrence that his characters “discover their identities through their response to place.” Or to put it in the words of a different Lawrence — Lawrence Durrell, I believe “we are all children of our landscape.” We are, I have tried to show in my writing not just who and what we are. We are shaped by where we are. Place works on us just as do events and people, and we become — or have the capacity to become — a different person in a different setting.

I would go further and maintain that travel for me is a kind of writing, an alternate text, a preliminary draft. It isn’t just a way to escape, as Graham Greene put it, or a way to gather material or battle against boredom. It is an act of creativity in which the world is an empty page and I’m the pen scrawling looping, recursive lines across a landscape. The goal in each case is the same — insight, joy, euphony, vivid experience, visual excitement, sensuous delight and discovery. Safer than alcohol, cheaper than heroin, it’s my method, a la Arthur Rimbaud, of systematically deranging my senses, opening myself up to the new and unexpected.

Having said that, I don’t want to leave the impression that I’m just another eager learner, an autodidact in an airplane or an automobile. As I mentioned earlier, travel for education has a long and laudable tradition. But frankly, at least at first, ignorance has advantages for a novelist. Personally I like going places where I don’t speak the language, don’t know anybody, don’t know my way around and don’t have any delusions that I’m in control. Disoriented, even frightened, I feel alive, awake in ways I never am at home. All of my senses suddenly come alert again and I can see, hear and smell — and afterward if I’m lucky I can write.

Black pages, blank spaces on the map, for me they are much the same. I am always eager to get to the bottom of a mystery I am constantly in the process of formulating. Although neither urge is entirely explicable, I know that why I write has a great deal in common with why I travel, just as how I go about doing both is best expressed by a line from Theodore Roethke. “I learn by going where I have to go.”

See more: