Since remote antiquity, for all kinds of reasons, people have left home and hit the road. Couriers and diplomats, merchants and worshippers crisscrossed the Mesopotamian triangle well before 3000 BC. Even tourists, travelling for pleasure, left graffiti on the Pyramids by 1500 BC. Very early in history, then, travel and writing converged. Homer’s Odyssey, the epic of obstacle-ridden travel in search of home, raises the journey to the status of a symbolic quest––an ‘odyssey’––and the traveler to that of archetypal trickster-hero. Early nonfiction travel writing illustrates the difficulty, continuing through the ages, of sorting fact from fiction in the genre. The Greek writer Herodotus gives us a mélange of myth, history, and geography, from Lydian customs (‘the daughters of the common people . . . practise as whores to collect dowries for themselves’) and how much wine is drunk at the Egyptian festival of Bubastis to the genealogies of the gods.

Even the guidebook, still a staple of travel writing, made an ancient début. In the second century ad Pausanias compiled a Guide to Greece for Roman tourists, including such attractions as the Acropolis and the Oracle at Delphi. In the Middle Ages, pilgrims generated an entire tourist industry with set itineraries and pre-packaged sites. The history of pilgrimage brings out the multiple, mixed motives and the moral as well as physical dangers attending even such an ostensibly pious quest. Sincere devotion mingled with simple wanderlust, or the urge to escape one’s sodden, smelly cottage after a long winter. The clergy denounced curiositas, the lure of worldly distractions along the way; hope of sexual adventure no doubt set more than a few pilgrims in motion. (An eighth-century missionary asked that matrons and nuns be barred from Continental pilgrimage, since ‘few keep their virtue. There are many towns in Lombardy and Gaul where there is not a courtesan or a harlot but is of English stock.’) Pilgrims’ snobbery and souvenir collections, displaying the badges they bought at various shrines, provided themes for satirists in the later Middle Ages. Travel fulfils obligations and enhances status, but it also feeds dangerous desires. A traveler might come back transformed––for better or worse––or might not come back at all.

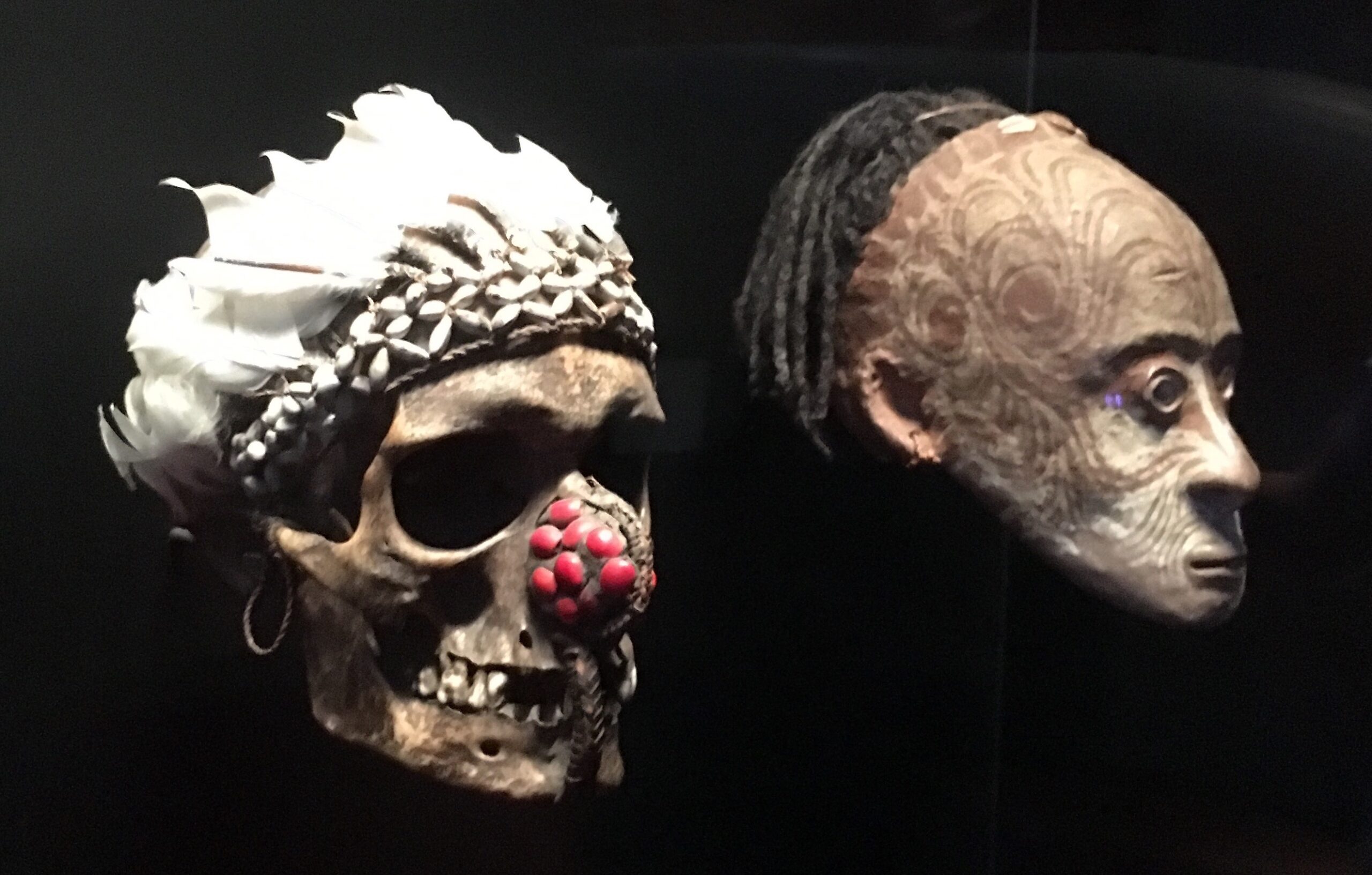

The Crusades are a second mode of medieval travel that looks ahead to travel’s more recent history. This massive influx of conquest-obsessed European Christians into the Middle East to confront ‘Saracens’, different in religion and culture from themselves, prefigures the cultural confrontations of later exploration and colonization. Sir John Mandeville’s famous Travels (1356)––a book owned by Leonardo da Vinci, Christopher Columbus, and the early Arctic explorer Martin Frobisher, among others––looks both backward to Herodotus’s travel mythology, with tales of one-eyed giants, headless men, and mouthless pygmies, and forward, with a remarkably tolerant account of Muslim attitudes and practices. One scholar of medieval travel sees Mandeville as initiating a new attitude: the medieval paradigms of pilgrimage and crusade gave way to new modes of engagement with observed experience and curiosity about other cultures. Along with Marco Polo, another near-mythical medieval traveller, Mandeville profoundly influenced Christopher Columbus, giving travel writing a continuity belied by the newness of Columbus’s discovery to European readers.

The period covered by this anthology begins after the ‘heroic age’ of early modern exploration. Drake circumnavigated the globe, Raleigh ‘discovered’ Guiana, and Thomas Hariot and John Smith crossed the Atlantic and founded the so-called First Empire, England’s colonies in North America and the Caribbean, well before 1700. And they wrote about it: as exploration came to serve royal and mercantile interests in a more organized fashion, reporting became an integral part of it. England got a relatively late start on all this, lagging eight decades behind Spain and Portugal, which helps account for the patriotic, competitive strain in English travel writing exemplified by the great editor Richard Hakluyt in the pioneering collections of voyages that he published starting in 1589.

Some travel reports, of course, were top secret, proprietary documents of great potential value as merchants and governments competed for territories and markets. But those that were published quickly captured an avid readership in England’s print market, whose rapid growth was a defining feature of the period covered by this book. Already top sellers in the relatively limited Elizabethan and Stuart book market, travel books continued to dominate the market throughout the eighteenth century as literacy rose and authorship burgeoned. The expansion of the print market changed literary history forever, bringing with it a new and popular fictional form––the novel––as well as an influx of authors new to print, including many women and middle-class men. A number of these appear in this anthology. Women travelers wrote, though they did not publish their travels as often as did men; women certainly wrote far fewer travel books than novels. And many of the male authors we include can be reckoned middle class, starting with the famously bourgeois journalist, novelist, entrepreneur, and sometime spy Daniel Defoe. Though a number of male travel writers, notably Grand Tourists like Joseph Addison and James Boswell, display the classical education that defined the gentlemanly élite of the day, many others––explorers like Captain Cook or David Thompson or colonists like Watkin Tench––are from a less privileged background. And a few, such as the sailor John Nicol and the slaves Olaudah Equiano and Mary Prince, are downright plebeian.

This brings up an important and somewhat controversial question, central to our selection: who counts as a traveler, or a travel writer? Paul Fussell, editor of The Norton Book of Travel, prefers fairly restrictive criteria. ‘To constitute real travel’, he declares, ‘movement from one place to another should manifest some impulse of non-utilitarian pleasure.’Although it could be argued that even the most utilitarian of travelers enjoys such pleasure at some point in the journey, to privilege this element is to skew the definition of travel, and travel writing, in the direction of an aestheticism that is the hallmark of a leisured élite. As the historian James Clifford puts it, ‘The traveler, by definition, is someone who has the security and privilege to move about in relatively unconstrained ways. This, at any rate, is the travel myth.’ But what about those whose movement is not so free, not so secure? Do sailors, soldiers, servants, slaves, emigrants, exiles, transported convicts, military and diplomatic wives, count as travelers? Fussell’s attitude emerges from a passing remark in his introduction to what he calls ‘the heyday of travel’, the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. ‘Porters were indispensable then because you carried so much.’ ‘You’, in this view of the world, were never a porter; ‘you’ were the porter’s employer, owner of all the baggage he had to carry.

And of course ‘you’ were also never a ‘native’, one of those inhabiting the places the traveler travelled to see. The involuntary travel of ‘natives’ makes up the mass population movements that define the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: emigrants, immigrants, refugees, diasporas, Gastarbeiters, and ‘illegal aliens’. Even in the eighteenth century, however, natives travelled too: Omai, the Polynesian brought back to London by Captain Cook in 1774, became a social sensation who met the King and had his portrait painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Before Omai, there were the four ‘Indian Kings’ from New York brought to London in 1710 to meet Queen Anne, plead for more military aid to colonists against the French, and be treated to urban amusements including the theatre, cockfighting, bear-baiting, and a Punch and Judy show. (Not to mention the seventeenth-century Indian Princess Pocahontas, who married a colonist––not Captain John Smith––and ended her days in England.) And Olaudah Equiano’s moving account of his kidnapping and enslavement reminds us of a form of mass involuntary travel that shaped the Atlantic world: the slave trade, which during the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries removed some six million Africans from their homes, transplanting and transforming those who survived the passage to the Americas. Very few of these travelers had the opportunity of getting their stories into print. We have included excerpts from slave autobiographies by Equiano and Mary Prince (the only surviving British slave narrative by a woman slave) partly to encourage readers to reconsider and broaden their understanding of what constitutes travel.

Clearly, authorship was more accessible to members of groups with higher status, and this reality has necessarily shaped our selection. As interesting as it would be to read Omai’s Impressions of London, he did not write or even dictate them for publication. But we have done our best to include travel writers of varying social ranks and occupations and both sexes. And importantly, we have not necessarily preferred writing that self-consciously foregrounds the writer’s personality or persona, that is romantic or ironic or otherwise highly ‘literary’ in the present-day sense of the term. Rather, we have striven to do justice to the range and diversity of material that was written, published, purchased, and read concerning travel between 1700 and 1830, and the variety of writers who produced it.

Who were they? Some of the most important kinds of travel writer are familiar from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: diplomats, merchants, explorers, colonizers, and scientists. Other types were relatively new, either to travel or to writing. Modern tourism began to flourish during this period. We will have more to say about tourism, but first let us run through the more utilitarian types of travel and their impact on travel writing at this time.

If the early modern period saw a shift in the ethos and language of travel writing ‘from chivalric adventure to venture capitalism’, the eighteenth century saw mercantile capitalism mature and mesh with national interests in imperial expansion. Parts of the globe still unknown to Europe were explored in search of potential profit, exploitable real estate, scientific knowledge (the Royal Society for the Improving of Natural Knowledge was chartered by the King in 1662), and national as well as personal prestige. We see these intertwined motives in Captain Cook’s famous Pacific voyages in the 1770s, the first commissioned by the Admiralty ostensibly for scientific purposes (to observe the transit of Venus from the southern hemisphere), but really to find the mythical Southern Continent and assess its potential for colonization. And soon it was colonized, initially as a dumping ground for Britain’s convicts, since North America was no longer available for that purpose. Cook took along scientists and artists to collect, classify, and document his discoveries. The official accounts of his voyages, anxiously awaited by the reading public, were runaway bestsellers––by far the most popular travel books of the age.

Business, exploration, and science came together in other ways in other areas of the world penetrated by the British. The fur trade had opened up large areas of North America during the seventeenth century; the Scottish fur trader Alexander Mackenzie in 1793 was actually the first European to cross the North American continent and reach the Pacific. Native American trappers guided other explorers such as Samuel Hearne and David Thompson to remote reaches of the continent. The grim business of the slave trade, of course, had linked Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean in the so-called Atlantic Triangle since shortly after Columbus’s voyage, though the British did not get involved until 1560. The vested interests of slave traders and slave owners color much or most of the writing about these areas until the 1788 founding of the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa by twelve members of an exclusive London club. One founding member was Sir Joseph Banks, the amateur botanist who sailed with Cook on his first voyage. Banks went on to become President of the Royal Society for many years, hatching, among other global projects, Captain Bligh’s luckless attempt to ship breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the West Indies as a food source for slaves. (After the mutiny on the Bounty and his astonishing survival, Bligh made a second, successful expedition.) Banks’s scientific contacts crisscrossed the Empire, shipping back specimens for his collections, exemplifying the global reach and interconnection of the British interests served by eighteenth-century travel.

The African Association, as it was known, sponsored expeditions into the interior of the continent by intrepid or foolish explorers such as Mungo Park, whose deservedly famous narrative we excerpt below. The critic Mary Pratt connects interior exploration with natural history as part of a new age of European ‘planetary consciousness’, ambitiously aiming to fill in all the dark places on the map or classify all existing species. To narrate their part in fulfilling these grand aspirations, however, explorers like Park or John Barrow construct innocuous personae: the benign naturalist, collecting and classifying his herbs (Barrow), or the lone European (Park), at the mercy of his African hosts, whose body becomes a curiosity for their inspection and whose stated motive of mere curiosity for his epic journey makes him a madman in their eyes. Pratt labels this rhetorical stance in travel writing ‘anti-conquest’. The imperial agendas that propelled so many British travelers of this period fade into the background, so to speak, in the travel writing they produce, upstaged by science, sentiment, or simply local color.

Closer to home, tourism––which has come to dominate and deform popular ideas about travel––took root in Britain during the period covered by this book. ‘The tourist’, James Buzard summarizes, ‘is the dupe of fashion, following blindly where authentic travelers have gone with open eyes and free spirits.’ That (to echo Clifford) is the tourism myth. ‘The tourist’, Evelyn Waugh commented caustically in the 1930s, ‘is the other fellow.’ Most travelers, however, even those who would scorn to think of themselves as tourists, actually move about within predetermined, quite limited circuits and itineraries, ‘dictated by political, economic, and intercultural global relations (often colonial, postcolonial, or neocolonial in nature)’, and of course by the available infrastructure of transport and accommodation. Though the word ‘tourist’ came into use in the late eighteenth century, the roots of Continental tourism as an English institution go back to the 1600s. The Grand Tour of Europe as a finishing school for young aristocrats originated under the Tudors. As early as the reign of Henry VIII, the diplomat Thomas Wyatt brought back from his Italian travels a novel souvenir: an exciting new poetic form, the sonnet. In 1642 the first Continental guidebook, James Howell’s Instructions for Forreine Travel, came out and was in demand for a number of years. Two centuries later, at the end of the period we cover, the Grand Tour had become available to the bourgeoisie and was on the verge of being further democratized by railways and Cook’s Tours.

We will have more to say about the Grand Tour, and domestic tourism, in section introductions. Since 1700, leisure travel––travel ‘for pleasure or culture’ (OED)––has become a widely prevalent practice (and a bloated industry) whose written records disclose a great deal about the values, desires, and the very structure of the modern self. Though we might not go as far as one theorist who proposes the tourist as the prototypical modern subject, we include writings by early tourists who tell us as much about themselves and their home culture as about the places and cultures they visit. Ambivalence is typical of the tourist: travel can reinforce satisfaction with England, articulate and strengthen national identity, while at the same time fulfilling desires for escape, transgression, and the exotic. In travel accounts such as Charlotte Eaton’s Narrative of a Residence in Belgium during the Campaign of 1815 and Walter Scott’s Paul’s Letters to his Kinsfolk we see the battlefield of Waterloo being made into a tourist attraction––a profitable commodity for developers and promoters––within weeks of the battle. This early in the nineteenth century, then, tourism was a well-established institution, ritually transforming bourgeois longings and national values into admission fees and souvenir purchases.

Travel writing as a form or genre is not easy to pin down. We think of it as having a narrative core, the story of a journey, yet eighteenth-century travel writing often includes as much impersonal description as first-person narration. We think of it as non-fiction: travel writers ‘claim––and their readers believe––that the journey actually took place, and that it is recorded by the traveler him or herself ’. And yet travel writers avail themselves copiously of the devices of fiction and have been labelled liars through the centuries. Fictional voyages were certainly among the bestsellers of the eighteenth century. Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Gulliver’s Travels (1726) both piggybacked on the popularity of non-fiction travel accounts. Swift cleverly satirizes travel writers’ often deadpan style and readers’ credulity. Defoe, in his fiction as in his travel writing, plods through a long-winded, doggedly concrete re-creation of the circumstances of travel and the features of place. Indeed, many of the century’s best-known authors published travel books alongside their other writings (many excerpted here): Addison, Fielding, Sterne, Smollett, Johnson, Boswell, Thomas Gray, Ann Radcliffe, Helen Maria Williams, Mary Wollstonecraft, Walter Scott, and William Wordsworth (as well as his sister Dorothy). Travel was a staple of fictional plots, from the picaresque rambles of Fielding’s Tom Jones and Smollett’s Roderick Random to the dramatic abductions of Radcliffe’s Gothic heroines and the Highland adventures of Scott’s Edward Waverley.

Travel writing and the novel overlap in a number of ways. Travel writing was popular before novels: J. Paul Hunter, describing the market niche targeted by early novelists, notes that their title-pages often ‘tried to capitalize on the contemporary popularity of travel books by suggesting the similarity of their wares’. One feature shared by the two genres is thematic: like travel writing, the early novel ‘is a product of serious cultural thinking about comparative societies and the multiple natures in human nature’. Formally, novels and travel books have in common an enormous flexibility. Both are ‘loosely constructed, capable of almost infinite expansion, and susceptible of a great variety of directions and paces’.

Like travel writers, too, early novelists sought ways to cope with being called liars. For example, the narrator of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko, or the Royal Slave (1688), set in the South American colony of Surinam, protests, ‘I was myself an Eye-Witness to a great part, of what you will find here set down.’ In her dedication Behn hammers home the claim: ‘This is a true story . . . If there be any thing that seems Romantick, I beseech your Lordship to consider, these Countries do, in all things, so far differ from ours, that they produce inconceivable Wonders; at least, they appear so to us, because New and Strange.’ She is using the features her book shares with travel writing––the ‘Romantick’ appeal of New World ‘Wonders’, a byproduct of geographical and cultural difference––to fend off the accusations of lying that beset the early novel, before fiction writing gained legitimacy. Oroonoko is widely considered a generic hybrid, combining elements of travel writing, romance, and novel, to the extent that it was possible to separate these in 1688. Stephen Greenblatt has identified the experience of wonder as ‘the central figure in the European response to the New World, the decisive intellectual and emotional experience in the presence of radical difference’. Building on two centuries of European writing about New World wonders, Behn is able to present her fiction as ‘strange, therefore true’ (whether or not she actually went to Surinam). Much early exploration writing dwells close to Oroonoko in a grey zone of the strange, exotic, and wondrous––not independently verifiable, and thus dependent on the force of rhetoric to compel reader belief–– although the realm of verifiable factuality in travel writing expanded as the eighteenth century wore on.

Much travel writing also shares with Oroonoko its generic and discursive hybridity. Besides the fictional elements of plot and narrating persona, whose prominence and coherence vary widely, travel books often incorporate pockets of historical anecdote, advice to the traveler (on everything from transportation and inns to how to avoid offending the locals), and proto-ethnographic ‘manners and customs’ description. Natural history was a staple of travel writing even before, but more importantly after the Swedish taxonomist Linnaeus’s epochal 1735 publication of The System of Nature. His disciples ‘fanned out by the dozens across the globe’ to describe, draw, classify, and collect new species. Later in the century, the language of aesthetics, describing the picturesque and sublime in natural and man-made landscape, entered travel writing to become a nearly indispensable convention, as we will see.

In what other ways did English travel writing change between 1700 and 1830? Well before 1700, amid the chaotic variety of the genre, some basic conventions were in place. The most typical form was the ‘report’ or ‘relation’, combining a chronological narrative of a journey with topographical and ethnographic descriptions. In the 1660s the Royal Society published instructions for scientific travelers, calling for accurate observation and a sober, unadorned prose style. As early as the 1620s the Grand Tourist, too, was instructed in detail, in print, on the ‘things to be seen and observed’ Travel was to educate both the traveler and the reader of travel books. Amid all this edification, it is not surprising that early eighteenth-century travel writing subordinates––often nearly banishes––the traveler– writer’s individual, subjective experience. Addison’s influential Remarks on Italy (1705), excerpted below, typifies the impersonality expected of travel writing throughout at least the first half of the century. Following the Roman critic Horace’s famous dictum about poetry, travel writing was expected to delight as well as to teach. The delight, however, was to come from acute observation and judicious reflection, rather than from the kind of autobiographical material that became more conventional in nineteenth-century travel writing. Otherwise a writer risked reviewers’ accusations of egotism, a cardinal fault.

When did this change? We hear these strictures both echoed and rejected as Mary Wollstonecraft (herself a reviewer) admits in her ‘Advertisement’ to Letters Written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796), ‘In writing these desultory letters, I found I could not avoid being continually the first person––“the little hero of each tale”. I tried to correct this fault, if it be one, for they were designed for publication; but in proportion as I arranged my thoughts, my letter, I found, became stiff and affected.’ Barbara Korte explains the gradual movement toward greater subjectivity in English travel writing during the last half of the eighteenth century partly through the expansion of the print market, which made information about the Continent more available at home. In response, travel writers ‘discovered’ new areas, away from the set Grand Tour itinerary––Boswell in Corsica, Brydone in Sicily and Malta, Southey in Portugal, Wollstonecraft in Scandinavia––but also turned to formal and stylistic innovation, even when writing about familiar routes. The increasing value attached to subjective experience in many areas of late eighteenth-century culture, especially philosophy and literature, is well known. It is no accident that travel writing during this time was published more often in the overtly autobiographical forms of journals, diaries, or letters. And we cannot overlook the widespread influence of Laurence Sterne’s bestselling travel novel A Sentimental Journey (1768), whose protagonist, the mischievously named Parson Yorick, rambles through France on a ‘journey of the heart’, looking for persons and situations to touch his emotions and educate his moral sense.

Some scholars see a cleft opening up between literary and scientific travel writing during the Romantic period (1790–1820). Barbara Stafford, for instance, sees the ‘synthetic merits’ of the Enlightenment travel account giving way during the first decades of the nineteenth century to ‘the purely entertaining travel book’ on the one hand, and on the other ‘the instructive guide (the ancestor of the Baedeker volumes)’. Pleasure, she asserts, ‘was no longer inextricably tied to instruction’. Nigel Leask, however, disagrees. His recent study sets out to revise the standard account of ‘romantic travel writing’, which he says ‘elevates the importance of one, self-consciously literary, strain of travel writing at the expense of other discourses of travel which were of equal importance’. Although the areas that are Leask’s focus in Curiosity and the Aesthetics of Travel Writing 1770–1840 (India and Mexico) are not among those we have chosen to include, his contention that travel writing at least until 1820 continues to struggle ‘to integrate . . . personal narrative with “curious” or “precise” observation’, to balance ‘literary and scientific discourses’, deserves to be tested against a wider range of writings.

Our principles of selection in this anthology arose, in the first place, out of our belief that travel as a cultural practice and travel writing as a literary genre cannot be properly understood by segregating domestic from exotic travel. In a period that saw such a dramatic expansion of the British Empire, literate Britons’ global consciousness––fostered by reading travel books––shaped their perception of their home island. Conversely, explorers, colonists, and other adventurers carried with them a sense of their home country, often fed to some extent by their reading in domestic travel writing. Thus Dorothy Wordsworth, reaching for terms to describe the Scottish Highlands to English readers in 1803, declares that it ‘was an outlandish scene––we might have believed ourselves in North America’. Her brother William labels the filthy house of a Scots boatman ‘Hottentotish’. This reiterates, perhaps knowingly, Samuel Johnson’s infamous dictum in his Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (excerpted below): ‘Till the Union made [the Scots] acquainted with English manners, the culture of their lands was unskillful, and their domestick life unformed; their tables were coarse as the feasts of Eskimeaux, and their houses filthy as the cottages of Hottentots.’ Matthew Lewis compares a cove on the Jamaican coast to ‘the most beautiful of the views of coves found in “Cook’s Voyages” ’. Soon after, however, he comes upon ‘places resembling ornamental parks in England, the lawns being of the liveliest verdure . . . enriched with a profusion of trees majestic in stature and picturesque in their shapes’. Readers would miss something crucial about the travel writing of this period without reading domestic and exotic travel side by side.

British men and women went just about everywhere in the eighteenth century: from China to Peru, to Abyssinia, the Canadian Arctic, Constantinople, New Zealand, and Buckinghamshire. Rather than attempting to span a planetary range within a single volume, we have decided to represent discrete areas of particular historical interest. Our selections are organized geographically; we have chosen areas that offer a rich variety of writings and pose interesting questions to the reader. We begin with the Grand Tour, which became during this period a major institution of knowledge about European civilization and its cultural limits, marked by the outlying Ottoman Empire. In travel writings about the Near East we find evidence of the discourse that the critic Edward Said famously labelled ‘Orientalism’–– a body of powerful and enduring stereotypes––but we also see these stereotypes called into question. We then turn to the British Isles, where various discourses of travel writing, including antiquarian, economic, and aesthetic tourism, played a significant part in consolidating the new sovereign territory of the United Kingdom between the Acts of Union with Scotland (1707) and Ireland (1801).

The following three sections cover what is known as Britain’s ‘First Empire’, its colonial holdings before the loss of the United States and large-scale nineteenth-century territorial takeovers in the African interior and on the Indian subcontinent. Africa is included as part of the so-called ‘Atlantic Triangle’, connected by the sea routes of the slave trade to England and its island colonies in the Caribbean, although the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries also saw the British start to explore the African interior. The cultural impact of colonial slavery and the political debate over its abolition pervade travel writing about both Africa and the Caribbean up to slave emancipation in 1833. English travelers to North America also comment on slavery, though it takes up less space amid diverse responses to awesome nature, nascent democracy, and the Native American presence on the vast continent. Finally, the Pacific Ocean marks the farthest reach of what is, by the end of the eighteenth century, a truly global British influence. Cook’s sensational voyages and the colonizing of Australia represent the crowning achievement of centuries of maritime exploration. Writings from these voyages display the mastery that was the aim of scientific travel, but also reveal the resistance and conflict inevitably provoked by such colonial incursions.

We limit our selections to non-fiction prose travel writing, most of it published between 1700 and 1830. Unpublished sources include excerpts from Captain Cook’s original journals as well as some unpublished travel letters and journals, especially those by women, who were less likely to venture into public authorship at the time. Most excerpts are fairly short, but in each section longer selections represent authors whose work in the genre is especially interesting. Each of our sections is organized, not necessarily chronologically, but in subsections that make sense for that particular geographical and historical context. An introductory note for each area provides a more detailed account of historical contexts; further geographical and biographical information accompanies the selections themselves.

The value placed on travel writing relative to other literature between 1700 and 1830 was higher than it is today. Widely read by all classes of readers, it helped to shape the global consciousness of subjects at the center of the expanding British Empire and pervasively influenced other literary genres. Many of these writings have literary value in the traditional sense. But other kinds of value and interest, we believe, are found in first-hand accounts of encounters with radically unfamiliar cultures, peoples, religions, landscapes, and sensibilities. We have chosen these readings to give pleasure to readers like ourselves––armchair adventurers whose imaginations are braced by a salt breeze, whose curiosity embraces the globe and all it contains. Compiling this collection has been more fun than scholars are usually allowed to have. We hope it brings pleasure to its readers as well.

Excerpted from Travel Writing 1700-1830: An Anthology (Oxford World’s Classics) edited by Elizabeth A. Bohls and Ian Duncan.