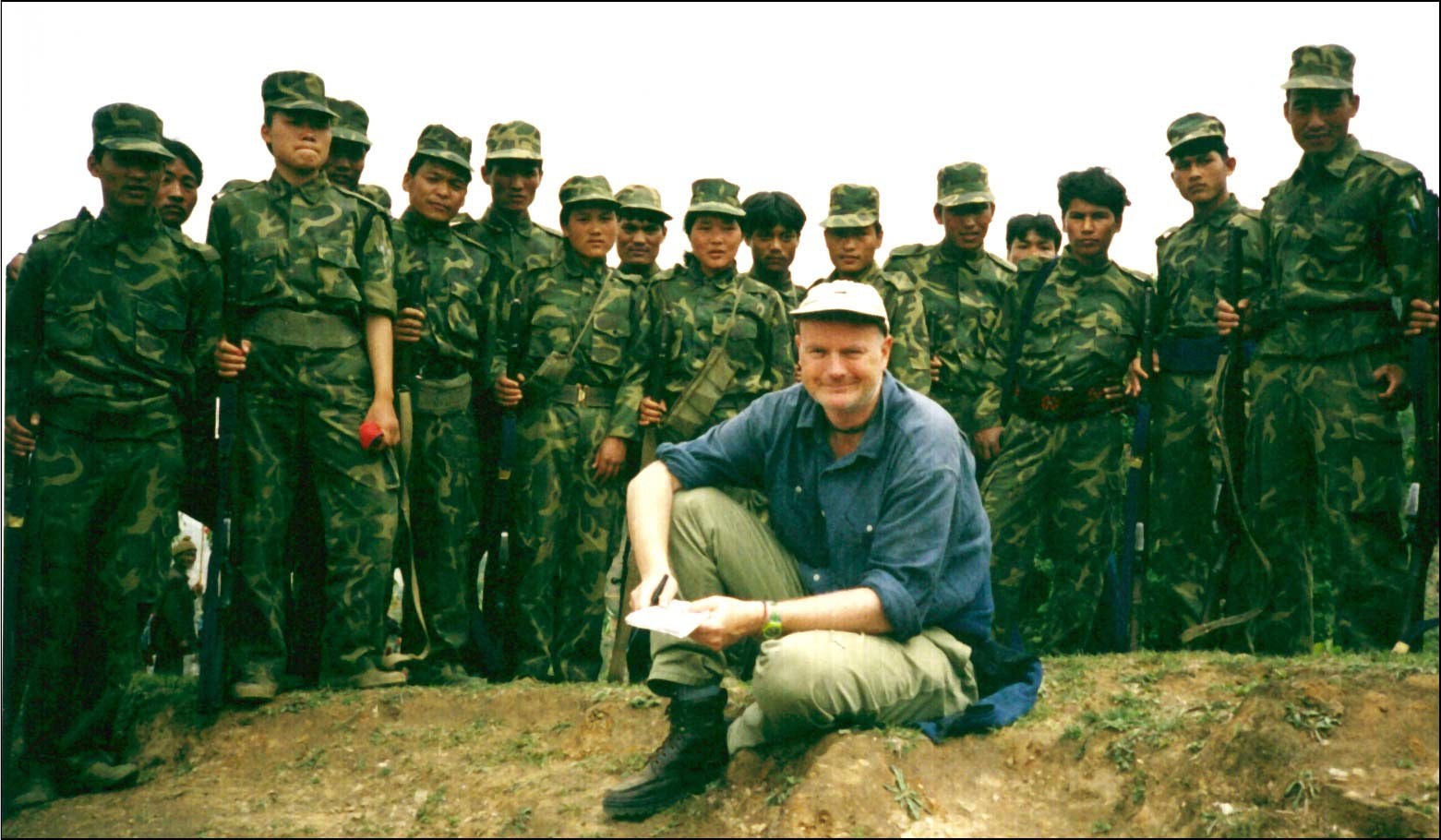

Patrick Symmes is a Contributing Editor at Harper’s and Outside magazines. As a foreign correspondent, he has traveled with Maoist insurgents in Nepal, visited both main guerrilla groups in Colombia, and profiled drug gangs in Brazil. His essays on Cambodia and Columbia have been selected for the “Best American Travel Writing” anthology, and he is the author of “Chasing Che: A Motorcycle Journey through the Guevara Legend,” an account of a 12,000-mile ride across South America, retracing the journeys and guerrilla campaigns of Che Guevara. He also writes frequently for GQ and Conde Nast Traveler.

How did you get started traveling?

I was tricked into it. Having spent my entire youth in one house and one school, I dreaded travel, foreign languages, and strange food, but a college roommate convinced me to visit New Zealand for a few weeks of hiking. A few weeks became a year — the food was strange, but they spoke English — and then I fell madly in love with a woman who abruptly decided to go across Asia. I followed her, of course, leading to three months of third class rail travel in China. From this, I learned to cherish the new, the different, the difficult, and the alien, and to feel at home in poor countries.

How did you get started writing?

At 18, I dropped out of college and found a job as a filing clerk at the Washington Post, where I noticed that journalists were generally allowed to leave their desks once in a while to go out in the sunshine and talk to people. At 20, I dropped out of college again to fill the position of a small town newspaper reporter who suddenly died, and by the end of the first day I was a published writer.

What do you consider your first “break” as a travel writer?

My first foreign dispatch was about Cuba, and published in the American Spectator, later famous as the wacko rag that called Bill Clinton a criminal and Anita Hill “a little bit slutty.” Although I had no ideological sympathy for them, I realized that if I picked my subject carefully and wrote what I believed, then I did not have to. Since then I have avoided the “internal politics” of the magazine business like the plague.

As a traveler and fact/story-gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

Not giving offense. I have made a specialty out of profiling guerrilla groups, drug gangs, and criminals in general. These “players” are extremely sensitive to criticism, and offending them could have terrifying consequences. Even in the most mundane circumstances, a traveler is dependent on the good will of strangers, and unfamiliar with the particular circumstances that could offend or anger them. Being careful is important.

What is your biggest challenge in the writing process?

Either getting started, or avoiding cliches.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint?

Financing trips. Although I almost always travel under contract, and get reimbursed for expenses, it can take six months of self-financed research to get an assignment, and then eight months to be reimbursed, so that I may end up spending money over the course of a year or more before I see the first penny in return.

Do you do other work to make ends meet?

No. I have never been able to hold another job and also write. In the early ’90s, I “temped” a great deal, but quit as soon as I had enough money to finance a spurt of writing or travel. The exception is casual photography for my own assignments, which generates extra income.

What travel authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

Whew! A random list of “travel” writers would include Paul Theroux, Eric Newby, Peter Fleming, Joseph Conrad, Bob Shacochis, Annie Dillard, Robert Stone, Wendy Gimbel (Havana Dreams), and Tom Miller.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

Look for your mistakes and learn from them, you are your principal teacher as a writer. Read well. Realize that travel writing is not “important” and be humble.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

Variety.