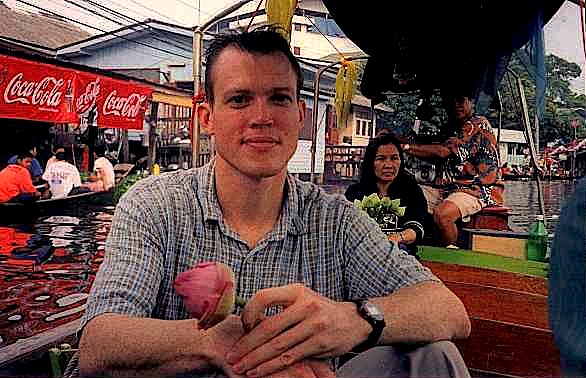

This morning, I went on my obligatory monthly visa run to Kawthaung, the small Burmese border town that lies about 20 minutes by boat from my temporary home in Ranong, Thailand. Ranong is where I come to hole up and get my writing done, so I always welcome this visa run, which takes me across the island-dotted mouth of the Pak Chan River, past trees laden with fruit bats and skies dotted with sea eagles. Kawthaung (known as Victoria Point in British colonial days) isn’t much to look at, but — as with all border towns — it’s a fascinating place. Though technically Burmese, Thai influence is strong, and one can see many other influences in the architecture and in the faces of the people: Chinese, Malay, Portuguese, Tamil, Karen, Mon, Moken. Some residents even have Japanese blood — the legacy of a brief World War II occupation. The name “Kawthaung” is itself a mongrelization: a play on the Thai koh song, or “two islands”.

Though the Thai-Burmese border here is largely an accident of colonial geography, I always like the feeling that comes when crossing the international boundary. It’s a feeling laced with newness and possibility — and this ongoing sensation is a big part of what makes travel so intoxicating.

On this particular visa run, I was joined in the boat by an Italian man and an American couple. The Americans had just been to Malaysian Borneo, and they described it in such a way that I wanted to drop everything and go there. That is, until the Italian started describing his adventures in Sumatra. I did the math and realized that — by a combination of bus and ferry travel — I could be in Sumatra within a day. It seemed so tempting and so plausible. Such is the wicked charm of Southeast Asia, where so many fabulous horizons seem so near and so desirable. It’s not just a matter of proximity, either: Bangkok, eight hours to my north, is one of the cheapest air travel hubs in the world. Auckland, New Delhi, Paris, Tokyo or Los Angeles are just a few hundred dollars away. Sometimes I do the math and try to think of how many connections it would take to get me to the more isolated destinations that have always fascinated me: Ethiopia, Armenia, Madagascar, Transnistria, Antarctica. To ponder this too long is to risk driving myself crazy with wanderlust. It’s a weird feeling to look at a world map and realize that you could go almost anywhere, yet know that it’s impossible to go everywhere. Such is the joy and the pain of the freedom that comes with travel.

Since my whole raison d’etre in south Thailand is to sequester myself and get work done, I finished my visa run this morning, mentally re-allotted my Borneo and Sumatra travels into the (not-too-terribly-distant) future, and got back to the solitary task of writing and reading and researching.

But even now, surrounded by notes and books, the notion of possibility weighs on me. Just as looking at a world map can be an exercise in both the allure and limitation of what is possible, so can walking into a bookstore. What, after all, do you read when you’re interested in most everything? Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises is on my list, since I’m going to Paris this summer. Robin Lane Fox’s biography of Alexander the Great is on the list — since if I can’t conquer the civilized world by age 32, I should at least read about someone who did. Without even mentioning the classics that languish on my to-read list, I hardly know where to start scratching my reading yen: Class, by Paul Fussell? Brown, by Richard Rodriguez? Video, by Meera Nair? What about No Sense of Place by Joshua Meyrowitz, The Ends of the Earth by Robert D. Kaplan, Fargo Rock City by Chuck Klosterman, Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace, or The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs? And, while these books are just the tip of the iceberg (which, as I write that, reminds me that I also want to read Iceberg Slim’s Pimp: The Story of My Life), I probably won’t be able to read them all this summer while still getting enough writing done to make a living.

So, resigned yet hopeful, I keep these books and destinations and possible futures on my list and get back to work, happy in the knowledge that — even if I could never do it all — there is so much out there for me to choose from.