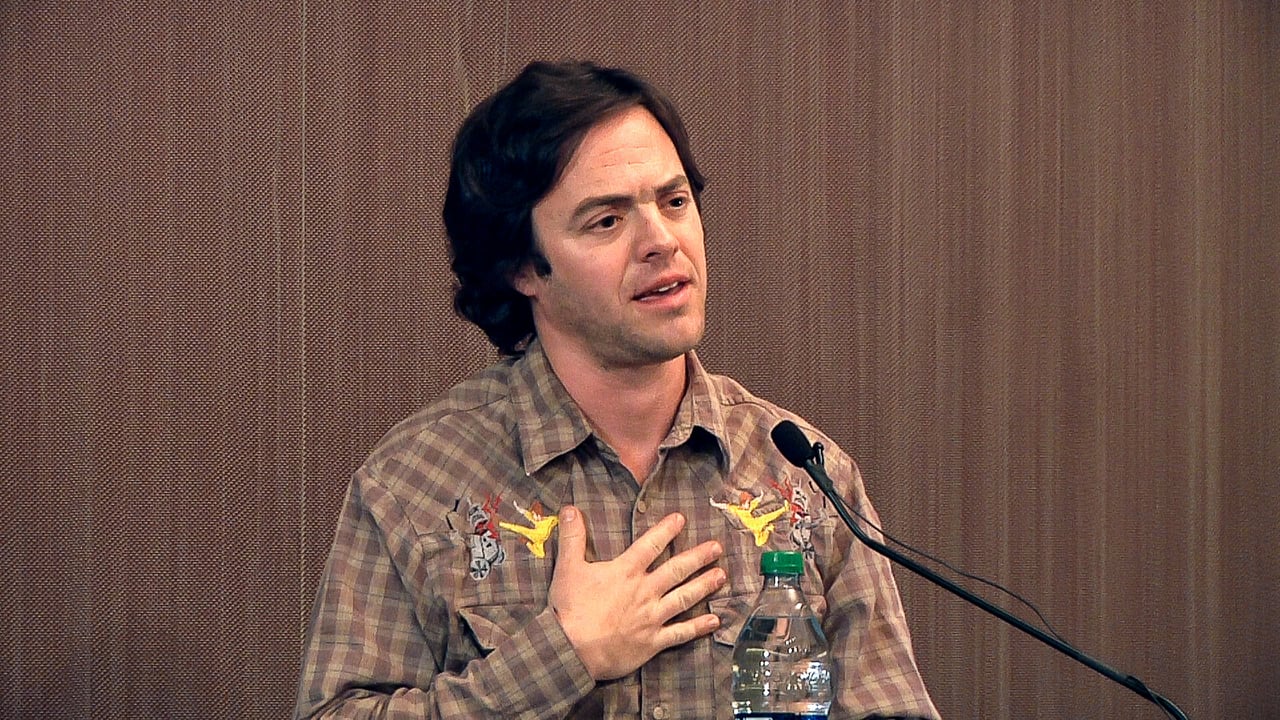

Matthew Gavin Frank is the author of Barolo (The University of Nebraska Press), a food memoir based on his illegal work in the Italian wine industry. Recent work appears in The New Republic, Field, Epoch, Crazyhorse, Indiana Review, North American Review, Pleiades, AGNI, The Best Food Writing 2006, The Best Travel Writing (2008 and 2009), Creative Nonfiction, Gastronomica, Plate Magazine, and others. He teaches creative writing at Grand Valley State University in Michigan.

How did you get started traveling?

Hmm. Perhaps it’s as simple as indulging an innate curiosity about the world. As a kid, I always went out of my way to uncover new shortcuts between places on my bicycle — finding a new park, triangle of prairie, dogless backyard, school football field penetrable only via a small opening in a chain link fence, section of train track to cut through. I loved the things that I’d find there. Somehow they felt foreign — windows into an alternative way of living. The glass shards of broken 40-ouncers and beer cans, sure, but sometimes an abandoned pair of blue jeans, the Black Sabbath cassette tape so sun blistered it wouldn’t play anymore, the tube of lipstick still streaked with the leavings of an implacably erotic red, and, as I hit puberty, the very placeable, and occasional, discarded porno magazine. Finding these hidden places and secret things in the neighborhood, as a kid, was as close to foreign travel as I could get then, and it woke in me that restless wanderlust. I remember my friend Jeff and I wanted to give guided tours of the neighborhood’s underbelly that we discovered by boy-exploring. As soon as I got my driver’s license, I hijacked my mom’s minivan — a 1986 Plymouth Voyager, maroon with faux wood trim — and spent the summer living out of a tent, road-tripping Michigan, which was then the edge of my world. After finishing college with a degree in creative writing (which led me directly back into the restaurant industry), I moved to Juneau, Alaska, sight unseen, but rife with romantic notions, with four-hundred bucks to spare. I moved into the cheapest motel in town — the Driftwood. Across the street stood this fiercely-local, intimidating breakfast joint — The Channel Bowl Cafe. It was connected to the local bowling alley and served everyone from the governor to the gold-panners, the commercial fishermen, and the guys who, Channel Bowl reindeer sausage notwithstanding, subsisted off of the land and sea. I ate there six days in a row, my assets dwindling, and on the seventh day, the owner offered me a job. Very biblical shit, I guess. Logic (perhaps illogic?) dictates that, for me, Europe was to follow, and Africa was to follow that, and, and, and… (My wife is from South Africa, and her family lives on an orange farm on the Mozambique border — a fact that has allowed me, among many other horror-joys, the wicked cold-sweat fever-dream paranoia induced by malaria meds). Like yoga and red wine, travel for me has been a healthy addiction. In travel is the ability to snap myself out of my comfort zone, which is exhilarating, informative, frightening, hallucinatory. All the good stuff. And it’s good for writing — my writing at least.

How did you get started writing?

It all began with the letter A (which is an upside-down picture of a yoked ox, a food-priority to early cultures; aleph directly translated from the Hebrew means ox). But I’m getting on a tangent. Soon I’ll be talking about the letter B’s relationship to ancient houses, so I better stop right now. Actually, I remember, in 5th grade (I was nine) collaborating with my friend Ryan Shpritz on a series of short gross-out stories. A couple of years ago, when my wife and I were visiting my family in Chicago, my mom brought down these scrapbooks she made when my sister and I were kids. Under the heading that asked for my interests, she wrote something like “Ghosts, blood, anything ghoulish.” This was when I was four or so, and my favorite thing to do was to trek out with my mom to the Vernon Area Public Library and, apparently, check out age-appropriate ghostly, bloody books. So my later collaboration with Ryan, on this series of (obviously) thematically-linked short stories called “Death at Dark” (I, II, III, and so on—we loved the nebulous Gothicism of the Roman numerals) had its roots in those early scrapbook-bound interests. Mrs. Buccheim (pronounced Buck-Hime), our teacher, allowed us to read our work in front of the class each week. Once, in “D at D” part VI, I think, some unlucky fellow caught his hand in a garbage disposal, and we compared the resulting carnage to a punctured egg yolk. After that, Mrs. Buccheim, bless her proper heart, put a stop to our public readings. Ryan’s a condo lawyer now, dealing with such problems as mold and bat guano. So the gross lives on.

What do you consider your first “break” as a writer?

Break-wise, I felt really good when I published my first poem (called “The Mark” in the Northwest Florida Review). Or when I found out, incidentally, from a co-worker (I was working as a sommelier in an Italian restaurant) that a piece of mine had showed up in the Best Food Writing 2006 anthology. That was exciting. But this is a tough question because I’m not sure I identify myself more as a writer, or cook, or teacher, or restaurant guy, or wine lover, or, or… I have a lot of interests, which demands juggling sometimes, and the attendant stressful freak-outs, but I’m rarely bored. If I ever really identified myself, in moments, as a writer, it was fairly recently. I used to drive an ice cream truck around Chicago and wore that occupation as a badge. For a while, I would call myself an ice cream truck driver to anyone who would listen. My first break as an ice cream truck driver came during a nasty heat-wave in Chicago — the elderly and the young were dropping like flies throughout the city; literally dying. My vehicle was an old converted mail truck, door-less, and with a hole rusted through the bottom through which the exhaust seeped. I was on an eight-snowcone-a-day fix just to keep cool, with an occasional ChocoTaco thrown in there for substance. But it was my job that summer to keep people cool, and alive. Yes: these are delusions of grandeur, but I’m aware of them. I remember writing shitty poems on cocktail napkins in that truck, parked while waiting for little league baseball games to finish. I’ve always written, have always been driven to write, have always obsessively tucked pen and paper into various jacket and pant pockets when leaving the house, have always stashed a notebook by my bedside to record those strange 3am dream-fueled musings that often sound like shit the next morning, but always, perhaps out of some forced self-deprecating suburban-Chicago Jewish guilt, resisted saying, if only to myself, OK, now I am a writer. Adding that “er” suffix lends some sort of career-y notion to the practice. But it must be said, after Barolo and Sagittarius Agitprop (my poetry collection) were accepted for publication, I tried the label out in the bathroom mirror, maybe even spoke it aloud a few times, then splashed some cold water on my face, walked to the kitchen, and made a chicken liver ice cream.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

Oftentimes, dough. Juggling employment, lodging (be it tent, motel room, flat…), and the time to write, take notes. I’m lucky in that my wife, Louisa, and I are on a similar wavelength when it comes to these things…most of the time. In Italy, when I was harvesting the Nebbiolo grape and mopping cantina floors, I was able to stay as long as I did by sleeping in a tent in the garden of a local farmhouse. I was paid in food and wine (supplemented with a very small stipend — enough for bus fare, bread, and the occasional truffle). I kept a very loose travel journal in a series of spiral notebooks purchased from the local tobacco shop, writing mostly in the evenings, at an outdoor table, with cold, red hands. When my wife and I were later seduced, on a road trip around the States, by New Mexico, we pulled up stakes and, again, looked to our tent. We lived for the summer out of that Coleman Cimarron, camping for free along the ski valley road outside of Taos. We bought this environmentally friendly soap and shampoo and bathed in the frigid Hondo River. We dried off in this makeshift arena of lawn-and-leaf bags that we set up in a circle of trees. Once a week, we would splurge, drive to the hostel in Arroyo Seco, pay the six bucks apiece and take a proper (and probably 40-plus minute) shower. After cooking breakfast on our propane stove, I would spend the rest of the morning and early afternoon accessing those Italy notebooks, and writing longhand at the picnic table in a new spiral notebook, while Louisa would hike in the mountains. Then, we’d go wait tables at night. This was how I wrote the first draft of Barolo. For writing prose, that kind of set-up was ideal for me.

Lately, though, and perhaps this has to do with aging, the biggest challenge has to do with the duel between the desire for some semblance of home and community, and the insistent wanderlust that continues to flex its biceps. Maybe after having lived in a few places (Alaska, Italy, Key West, et. al.), a little older each time, each move a bit more of a pain in the ass than the one that preceded it, I started thinking about the places, and people, I had left behind — following that rabbit hole all the way back to Illinois, where I was born and raised.

In 2006, Louisa and I had just, on a road trip, landed in Montpelier, Vermont, and decided we wanted to live there for a stretch. On the day we were to sign our lease, we received a phone call from my sister in Chicago telling us that my mom was sick. We fled Vermont, returned to Chicago for a year, lived in my parents’ house, and took care of the family while she battled illness (and won, thankfully). Remember: this was the first time I had lived there since I was seventeen, this time with my wife of five years in tow. It was crazy. Horrible. Amazing. After that year, being confronted with a parent’s mortality, I found I missed the Midwestern things I had forgotten about — the smells, the leaves, the cicadas, the lightning bugs. In this descent (or ascent) into home, I found myself reflecting on my life, placing it in some sort of futile context. This infected my writing with a strange honesty. Does this mean I’m being merely confessional? Attracted solely to the Midwest and the actual? It’s complicated, but no way. As if to balance this, I’m presently working on a series of short essays based on photographs I took in Oaxaca, Mexico, and a poetry manuscript based on couching the bad joke in verse. Its working title is “Your Mother.” These dueling desires are a source of beautiful conflict really. I can see settling for a stretch in the Midwest as much as I can see heading to Inner Mongolia for a year. It’s just that Illinois — what a surprise! — recently joined the tug-of-war. My wife, whose entire family still lives in South Africa, is dealing with the same conflict on a larger scale, I suppose. I think this conflict is a lucky one — the product, again, of rarely being bored, and wanting to do, and see, many different things.

What is your biggest challenge in the research and writing process?

I’m easily distracted. Sometimes this is a very good thing — good for research, good for writing. Sometimes, not so much. I was living in Alaska before I moved to Barolo. It was summer. After an Alaskan winter, without much sun, dealing with every patron and matron saint of the inhospitable, the outdoors, the hiking trails, the glacial lakes speak with loud voices. Sitting indoors and teaching myself the Italian language, as was my plan, inevitably took a back seat to a clear sky and weather that permitted, at sea level at least, short sleeves.

Now, I try to write, or do some form of writerly research everyday, but at unspecific times. Some days, it may be one line. Other days, twenty pages. Much depends on teaching schedule and season, which offer other challenges, time-wise. With poetry, it’s decidedly unscheduled. Writing prose is more of a labor for me than writing poetry — oftentimes certain lines around which I’ll build a poem leak from the celestial monochord, and I’m fortunate enough to be there to collect the drips. Writers (uh, oh: did I just call myself a writer?) pontificate about this all the time, so to clarify: the trick is to be holding the right kind of bucket. Mine is often plastic and red with a dagger drawn in black Sharpie on the side, wishing itself a rose. But it’s fooling itself. It’s a dagger. With prose, I’ll typically, on my days off, get up at about 10am (I like staying up late — after 18 years in the restaurant industry, I am, for better or for worse, a night person), pop in a CD — Hermeto Pascoal or Van Morrison; good morning music — lounge with some coffee, make some herbed eggs, eat ’em, and write for a couple hours. But it must be said: my bicycle and I have a very co-dependent relationship. I want to ride it. It wants me to ride it. Occasionally, I have little resolve, and will abandon my research or writing to go on a bike ride, maybe to the Grand Rapids community garden on Lyon Street, sit there a while, look at the sunflowers, maybe write a skeletal poem or a few lines of prose on a slip of scrap paper, and ride home. Some days, the bike ride will ignite something, and my research and/or writing will take off. Other days… well, I’m just easily distracted.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint? Editors? Finances? Promotion?

Luckily, I have thus far had nothing but great experiences with editors. Self-marketing is tough for me. So yes, finances. Yes, promotion. Louisa gives me shit all the time regarding my overuse of the word, parlay (as in, I wish I knew how to better self-market so I could parlay this writing thing into a financially-viable occupation). I try to spend some marketing time on the Internet, trying to learn, flogging many dead horses, an occasional live one — but as I said, I am easily distracted and have, in spades, what my late orange-haired Jewish grandmother Yiddishly called shpilkes.

Have you ever done other work to make ends meet?

Most of my work life has been spent in restaurants, or another faction of the food-and-wine industry — from washing dishes and bussing tables to working as a chef, sommelier, server, garde manger, manager… I co-founded the now-defunct Chicago Boys Catering Company in Juneau, Alaska, preparing such odd over-the-top items as Deconstructed Venison Osso Buco with Cremini-Venison Jus, Carrot Risotto, Braised Rainbow Shard, Saffron Ice Cream, and Bone Marrow Latte. Did I mention it was now defunct? I apprenticed in many kitchens throughout the States and Europe. I drove that ice cream truck. I packed computer parts into boxes in a warehouse. Ran the diesel ski lifts and did snow removal at a ski area in Alaska. Did some farm work — picking wine grapes and other fruit. Stored boats for the winter at the Alaska Ship Chandlers. Swept parking lots. Painted houses. Telemarketed (sorry for interrupting your dinner). Worked as a proofreader and editor for the National Council of Teachers of English (can’t you tell, given all these fragmented sentences?) I still do some freelance writing for journals and magazines. I teach creative writing now. I cleaned swimming pools.

What travel authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

Hell. This is a tough one. It’s hard to come up with a favorites list. Pico Iyer’s Video Night in Kathmandu, William Least Heat Moon’s Blue Highways, Fuchsia Dunlop’s Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper, Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard, Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek…. There are so many. I feel like Scarlet O’Hara, about to run the back of a lace-gloved hand over my perspiring forehead, purring my best poor-little-rich girl’s ‘Land Sakes!’ Ask me again tomorrow, and I’ll give you a different answer. Today’s answer is fueled by the jalapeño egg salad I just swallowed. The yolks are telling me to say Saul Bellow (even though he’s not really a travel writer, but…) — especially in Henderson the Rain King because he doesn’t allow his intellectualism to trump his whimsy, which is such a delight, such a guilty pleasure — like a good butterscotch. Though he creates a highly-fictionalized Africa, it’s a fully realized highly-fictionalized Africa which, well before I met my South African wife in a Latin jazz bar called Virgilio’s in Key West over mudslides and martinis, made me want to go to the real Africa.

Italo Calvino’s unfinished final work, Under the Jaguar Sun, is another great “travel” work. The title story deals with an autumn couple traveling through Oaxaca, Mexico, and reigniting their relationship through the cuisine there. The last line of this story is one of my favorites in any piece of food or travel writing.

As you know, I am obsessed with food and drink and still no one does food and drink and travel like MFK Fisher — she dives headfirst into the human and the sensual and I feel robbed by my birth-year because I never got to dine with her, never got to kiss her. Her writing makes me long to do, at least, both. I adore, of course, The Gastronomical Me, and her lesser known A Cordiall Water, which details various oddball medicinal recipes and practices, spanning place and time. The book inspired me not only to place-travel, but to time-travel as well — which can still be done in certain places it seems, like rural Africa — places that float outside of time, which, in a way, allows the traveler to similarly float, providing for future awkward conversations with folks who self-identify as “grounded.” My favorite anecdote in A Cordiall Water involves Fisher’s conversation with this ancient woman at a bus stop in Dijon. The woman tells her about her granddaughter’s death; how, the entire family gathered with the stymied doctor in a small, hot room around her deathbed; how the old woman went outside and gathered a bunch of frogs in a burlap sack and placed them on the dead girl’s chest. The trapped frogs hopped about in a failed attempt to re-ignite the girl’s heart. The old woman then got serious. She trapped a pigeon and, with a kitchen knife, sliced it open vertically, unfolded its body from its organs, and placed its still-beating bird-heart onto the chest of the dead girl. In an instant, the girl came back to life, sitting up with a deafening inhale. This story made me want to go to Dijon. That Dijon.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

Don’t skimp tent-wise. Purchase one that decently blocks out the rain. This is your home for a while. Make it so. Create a little nightstand in the corner with a stack of books you plan on reading, and your notebook. Keep your watch, glasses and lantern on it, each in their own little spot. It’s strange how that little consistency can go a long way in creating a small ease within the big exhilaration of traveling. If camping along the ski valley road in Taos, New Mexico, bring your own toilet paper, lest you want to succumb to the discarded Subway napkins the guy the next site over push-pinned to the pit toilet wall. When camping in Kruger National Park in South Africa, listen at night to the hippos laughing. Take notes throughout. Camp at Wonder Lake in Alaska’s Denali National Park in mid-September. Wake up in the middle of the night to see the aurora borealis dancing pink and green over the mountain. Write postcards you intend to send. In a pinch, when preparing ramen noodles over a propane camp-stove, choose the pork flavor; boil the noodles in half-water, half-pineapple juice. Contemplate the illusory makeup of gourmet. Remember: ratio is everything. Two cans of Stagg Chili + one can of Libby’s Corned Beef Hash = tolerable high-calorie meal. One can of Stagg Chili + two cans of Corned Beef Hash = digestive demoralization from the throat on down — this is a ratio that may cause you to abandon your current course, flee the woods, get on the first plane to Paris, and have a vegetarian dinner at L’Arpege. Write postcards you never intend to send. Meet your spouse in a Latin jazz bar on one island or another. Surrender. Even to strange street food — especially to strange street food — surrender.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

Perspective. Memory, however hazy and malleable. Vulnerability. Out-and-out fun. New smells, tastes, fears. Learning, reinventing, what comprises us. Dismantling and reassembling the nature of goodbye. Travel, and the subsequent writing can play the role of mother, father, son, daughter, lover, pet goldfish. It’s life-company. It’s prayer tugging-of-war with OCD. It’s reason and wayward — the real stuff. It’s family and enemy. All of whom demand love.