Wander through the 11th arrondissement of Paris toward the dead celebrities of Pere Lachaise Cemetery, and there’s a decent chance you’ll stumble across a small gallery called “Le Musée du Fumeur.” Unlike the hallowed halls of the Louvre or the Musée d’Orsay, there is no tyranny of expectation in this tiny, smoking-themed museum. No smiling Mona Lisa or reclining Olympia dictates where the random tourist should focus his attention. Thus left to meander, the drop-in visitor may well overlook the more earnest exhibits here — such as Egyptian sheeshas or Chinese opium pipes — and note the small, red-circle-and-slash signs reminding guests that, in no uncertain terms, smoking is strictly forbidden in the Museum of Smoking.

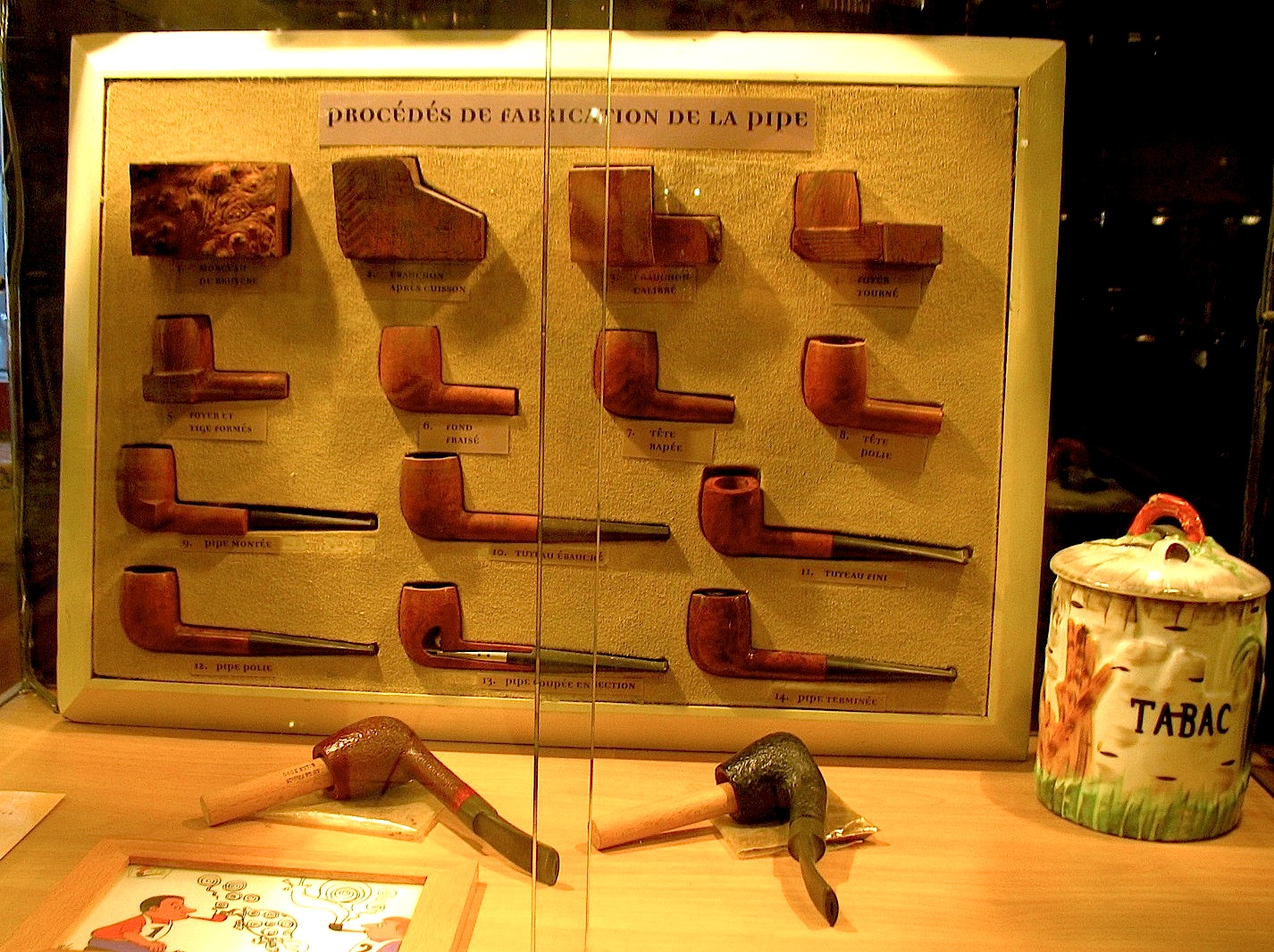

In spite of this startling contradiction, there is a notable lack of irony in Le Musée du Fumeur, which crams an eclectic array of international smoking-culture relics into a 650-square-foot storefront near Rue de la Roquette. Inside the glass display cases, hemp-fiber clothing competes for space with 17th-century smoking paraphernalia and sepia photos of American Indian chiefs posing with peace pipes. Around the corner, a looped video about Cuba’s cigar industry flickers above 1920s-era etchings of cigarette-toting debutantes and scientific drawings of tobacco plants. Out front, the gift shop hawks highbrow cigar magazines alongside glass bongs and rolling papers; DVDs produced by High Times perch on the same shelf as pamphlets on how to quit smoking. A curious-looking machine, the “Vapormatic Deluxe,” which apparently allows one to inhale plant essences without creating secondhand smoke, retails for 299 euros.

In a more provincial part of the world — rural Moldavia, say, or a Nebraska interstate exit — such an unfocused array of smoking esoterica might well be relegated to some dank basement, advertised by fading billboards and listed in guidebooks alongside Stalinist monuments or concrete dinosaurs. But this is Paris, and the displays here are sleek, self-serious, tastefully illuminated and studiously clean; soft jazz mood-music alternates with piano and harpsichord compositions as you move from display to display. The closest thing to pure whimsy is a psychedelic mural painted in the back room — an oddly smoke-free scene, wherin cats strum guitars, flying robots clutch cans of beer, and busty women hitch rides from VW camper vans.

The ostensible purpose of Le Musée du Fumeur is to demonstrate how global attitudes toward smoking have developed and transformed over the years. Yet its cluttered formality can leave visitors with the impression that smoking is in fact an archaic practice, long-since vanished from mainstream society. And given current trends, it might not be long before cigarette smoking indeed does become extinct — at least in the public spaces of progressive, First World cities like Paris.

Not too long ago, public smoking bans were regarded as a uniquely American phenomenon — a puritanical gesture, held in ridicule by any self-respecting, Gauloise-puffing Frenchman. Over time, however, the public health burden of smoking-related illnesses has spurred a number of industrialized nations to follow the American example. When the initial steps of a public smoking ban took effect in Paris this February, French opinion polls reported that 70 percent of Parisians were in favor of the prohibition.

With the rites of public smoking thus endangered, it’s tempting to conclude that a smoking-themed museum is a great way to preserve an increasingly marginalized social ritual. In truth, the opposite is probably more accurate: To paraphrase what sociologist Dean MacCannell said a generation ago about folk museums, the best indicator of smoking-culture’s demise is not its disappearance from public areas, but its artificial preservation in a place like Le Musée du Fumeur.

Moreover, it may well be that a museum is not the truest medium in which to commemorate something so habitual and prosaic. Social critic Lucy R. Lippard observed that museums are inherently alien to the artifacts they contain. Lippard noted that many people are “far more at home in curio shops, which slowly become populist museums,” home to relics and life-ways that are “displayed in a relaxed and random fashion…in ways far more attuned to how we experience life itself.”

As of now, the populist, curio-shop equivalent of musées du fumeur can be still found in the smoky confines of cafés, restaurants, and nightclubs in Paris — but only until January 1, when the smoking ban takes full effect, and anyone caught lighting up in such places is subject to a 75-euro fine. After that day, a million populist museum curators will be forced to puff their cigarettes on the street corners of Paris, and the Musée du Fumeur will become a slightly more potent curiosity.