By Roy Peter Clark

Good writers move up and down the ladder of abstraction. At the bottom are bloody knives and rosary beads, wedding rings and baseball cards. At the top are words that reach for a higher meaning, words like “freedom” and “literacy.” Beware of the middle, the rungs of the ladder where bureaucracy and public policy lurk. In that place, teachers are referred to as “instructional units.”

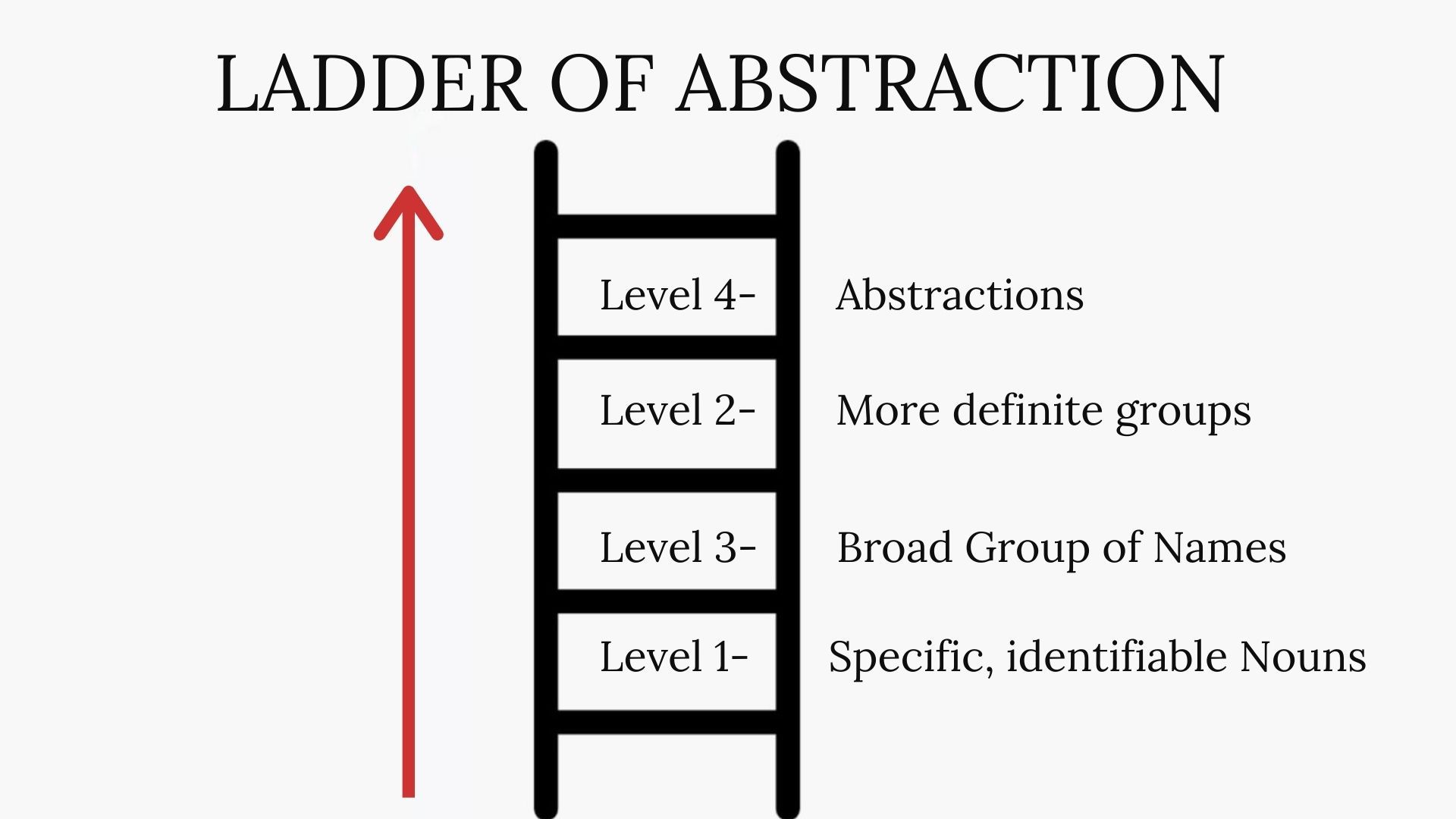

The ladder of abstraction remains one of the most useful models of thinking and writing ever invented. Popularized by S.I. Hayakawa in his 1939 book Language in Action, the ladder has been adopted and adapted in hundreds of ways to help people think clearly and express meaning.

The easiest way to make sense of this tool is to begin with its name: The ladder of abstraction. That name contains two nouns. The first is “ladder,” a specific tool you can see, hold in your hands, and climb. It involves the senses. You can do things with it. Put it against a tree to rescue your cat Voodoo. The bottom of the ladder rests on concrete language. Concrete is hard, which is why when you fall off the ladder from a high place you might break your leg.

The second word is “abstraction.” You can’t eat it or smell it or measure it. It is not easy to use as an example. It appeals not to the senses, but to the intellect. It is an idea that cries out for exemplification.

An old essay by John Updike begins, “We live in an era of gratuitous inventions and negative improvements.” That language is general and abstract, near the top of the ladder. It provokes our thinking, but what concrete evidence leads Updike to his conclusion? The answer is in his second sentence: “Consider the beer can.” To be even more specific, Updike was complaining that the invention of the pop-top ruined the aesthetic experience of drinking beer. “Pop-top” and “beer” are at the bottom of the ladder, “aesthetic experience” at the top.

We learned this language lesson in kindergarten when we played Show and Tell. When we showed the class our 1957 Mickey Mantle baseball card, we were at the bottom of the ladder. When we told the class about what a great season Mickey had in 1956, we started climbing to the top of the ladder, toward the meaning of “greatness.”

Let’s imagine an education reporter covering the local school board. Perhaps the topic of discussion is a new reading curriculum. The reporter is unlikely to hear conversation about little Bessie Jones, a third-grader in Mrs. Griffith’s class at Gulfport Elementary, who will have to repeat the third grade because she failed the state reading test. Bessie cried when her mother showed her the test results.

Nor are you likely to hear school board members ascending to the top of the ladder to discuss “the importance of critical literacy in education, vocation, and citizenship.”

The language of the school board may be stuck in the middle of the ladder: “How many instructional units will be necessary to carry out the scope and sequence of this curriculum?” an educational expert may ask. Carolyn Matalene, a great writing teacher from South Carolina, taught me that when reporters write prose the reader can neither see nor understand, they are often trapped halfway up the ladder.

Let’s look at how some good writers move up and down the ladder. Consider this lead by Jonathan Bor on a heart transplant operation: “A healthy 17-year-old heart pumped the gift of life through 34-year-old Bruce Murray Friday, following a four-hour transplant operation that doctors said went without a hitch.” That heart is at the bottom of the ladder — there is no other heart like it in the world — but the blood that it pumps signifies a higher meaning, “the gift of life.” Such movements up the ladder create a lift-off of understanding, an effect some writers call “altitude.”

One of America’s great baseball writers, Thomas Boswell, wrote this essay on the aging of athletes:

The cleanup crews come at midnight, creeping into the ghostly quarter-light of empty ballparks with their slow-sweeping brooms and languorous, sluicing hoses. All season, they remove the inanimate refuse of a game. Now, in the dwindling days of September and October, they come to collect baseball souls.

Age is the sweeper, injury his broom.

Mixed among the burst beer cups and the mustard-smeared wrappers headed for the trash heap, we find old friends who are being consigned to the dust bin of baseball’s history.

The abstract “inanimate refuse” soon becomes visible as “burst beer cups” and “mustard-smeared wrappers.” And those cleanup crews with their very real brooms and hoses transmogrify into grim reapers in search of baseball souls.

Metaphor and simile help us to understand abstractions through comparison with concrete things. “Civilization is a stream with banks,” wrote Will Durant, working both ends of the ladder. “The stream is sometimes filled with blood from people killing, stealing, shouting, and doing the things historians usually record, while on the banks, unnoticed, people build homes, make love, raise children, sing songs, write poetry, and even whittle statues. The story of civilization is the story of what happened on the banks. Historians are pessimists because they ignore the banks for the river.”

Originally published as “Writing Tool #13: Show and Tell,” by Roy Peter Clark, Poynter.org, May 19, 2004