Korea’s DMZ is one of the planet’s oddest tourist attractions, a place where visitors can pick up everything from propaganda to perfume.

By Rolf Potts

Just behind the video-projection screen in the basement of the Cass ‘N’ Rock sports bar in Pusan, Korea, there hangs a large red flag that reads: “If the South Would’ve Won, We Would’ve Had it Made.”

Never mind that this is a Confederate battle flag. Never mind that this slogan is written in English. Never mind that the flag also bears the visage of Hank Williams Jr.

At the Cass ‘N’ Rock — where Korean university students gather to drink beer, eat dried squid and watch soccer games on the big-screen TV — the South in question has nothing to do with Robert E. Lee, King Cotton or the Heart of Dixie. At this South Korean sports bar, the Stars and Bars banner is a quirky, sorrowful symbol of a different war — one that began 48 years ago, killed more than 2 million Koreans and resolved nothing.

For those keeping score at home, this war is technically not over: 250 miles north of the Cass ‘N’ Rock, upwards of a million troops are locked in a 45-year-old standoff between North Korean and United Nations Command forces along the most militarized border in the world.

Holding true to the absurdities of Cold War-era nomenclature, this border is called the Demilitarized Zone.

It’s just after 8 in the morning, and I am taking a USO bus north from Seoul to the DMZ. This trip is not as sensitive and dangerous as it sounds: Approximately 70,000 people took the trip last year, including President Clinton.

In the seat next to me, a 50ish woman from Virginia is entranced by the empty yellow countryside that surrounds us. She’s been staying in the urban madness of Seoul for four days, and she says she never knew that the Korean landscape could look so quiet.

But the landscape is not as empty as it appears at first glance. Gaze long at these roadside foothills and you can just make out trenches and camouflage netting, infantry soldiers and artillery. A mere 40 road miles separate Seoul from the entrenched front rank of a million-man North Korean army, and every inch of the space in between has been groomed to defending South Korea’s capital from attack. As we near the DMZ, the military presence becomes more obvious: razor-wire fences on the Imjin River, anti-tank barricades framing the highway, medieval-looking iron-spiked barrels gracing the asphalt.

The Virginian asks me if I’ve ever been scared, living and working in Korea for the past two years. I tell her that Korea is a strange place where gruesome traffic deaths are an hourly occurrence, rival sects of Buddhist monks get into public fistfights and department store buildings collapse because the local building inspectors live off bribes. If anything, I tell her, I am scared of getting run over by a delivery truck or smashed by a poorly installed I-beam. The threat of war is a forgettable annoyance that I think about only when a civil defense drill halts my bus when I am late for work, or when my middle-age landlady tells me how she learned to throw hand grenades in her high school gym class.

What I don’t tell her is this: If the North were to launch an all-out surprise attack on Seoul this evening, we’d stand about a 50-50 chance of living through the first hour. That’s a statistic I don’t dwell on much.

The paper I have just signed my name to reads: “The visit to the Joint Security Area at Panmunjom will entail entry into a hostile area and the possibility of death as a direct result of enemy action.” The 50 or so other people in the Camp Bonifas briefing room have all signed the same disclaimer, and a gangly, bespectacled U.S. Army specialist is handing out the green U.N. Command visitor’s badges that will allow us to proceed a few hundred meters farther up the road and enter the DMZ.

Despite the grim warning, no tourist has ever died while visiting the Joint Security Area. The U.N. Command troops haven’t always been so lucky. Since 1953, more than 50 American and 500 South Korean soldiers have died as a result of North Korean hostilities along the DMZ. Camp Bonifas itself is named for a U.S. Army captain who was summarily axed to death by North Korean soldiers while leading a tree-trimming detail in the JSA in 1976.

The lights go down in the briefing hall, and Spc. Vance begins showing us slides. The DMZ is 2,000 meters wide, he tells us, and stretches the entire length of the Korean peninsula. Minefields, anti-tank barriers and razor-wire fences installed by U.N. Command troops stretch from coast to coast to defend from a North Korean attack. Our tour group will soon enter the truce village of Panmunjom, the only official crossing point along the DMZ. Over the years, Panmunjom has gained notoriety as an exchange zone for prisoners, a meeting place for the Military Armistice Commission and — most recently — a crossing-point for 1,001 head of cattle donated to North Korea by a wealthy South Korean businessman.

Spc. Vance’s lecture touches on the history of the Korean War, but sidesteps the more embarrassing American details. For instance, we don’t learn that in 1945 a Europe-based U.S. Army colonel studied a National Geographic wall map for just 30 minutes before choosing to divide Korea into Soviet and American occupation zones along the 38th Parallel. We don’t learn that right-wing thugs appointed by the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea slaughtered as many as 30,000 people during a leftist insurrection on Cheju Island in 1948. We don’t learn how the June 1950 North Korean invasion of the South was inadvertently green-lighted when U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson forgot to include South Korea within the U.S. defense perimeter during a speech to the National Press Club six months earlier.

We do learn, however, that there are no toilets for tourists in the DMZ. Once the lights come back on, we all take our turn in the Camp Bonifas facilities before loading onto the bus and entering no man’s land.

I am now standing in North Korea, and the industrial-strength disinfectant odor reminds me of a similarly brief visit I made to the porn-theater peep booths in Times Square several years ago.

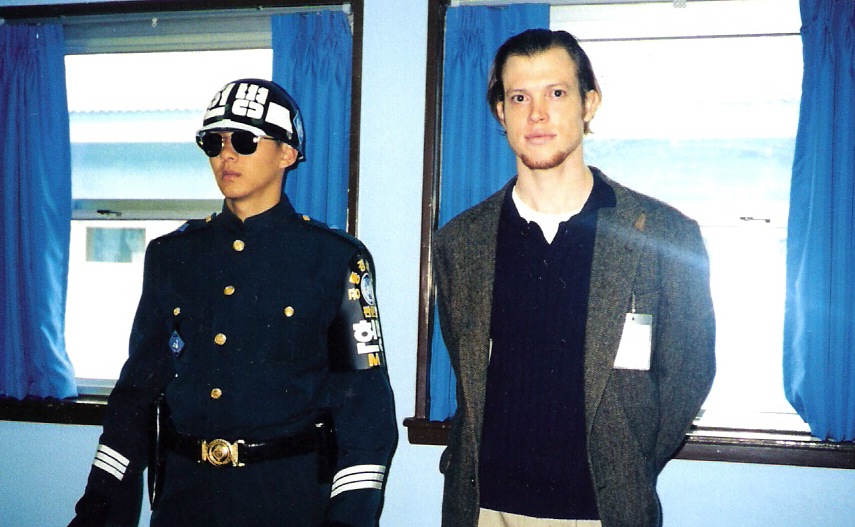

Across a conference table from me, the rest of my tour group stands in South Korea. They will all eventually get their chance to rotate into North Korean territory and take a few pictures. Spc. Vance explains how this Military Armistice Commission conference room precisely straddles the demarcation line that separates the two Koreas.

The Virginia woman and I swap cameras and take each other’s picture standing next to the tough-looking South Korean guards at the far end of the room. This is probably as far as any of us will ever venture into the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

The North Korea that stretches beyond this conference room has long been the weirdest, most isolated country in the world. Press releases from the official DPRK news agency often come off sounding like bad vaudeville jokes:

Question: How does North Korea solve its famine problems?

Answer: By publicly executing its Minister of Agriculture.

Don’t bother cueing the snare drum. This actually happened in 1997 — the same year that North Korea’s squatty, rotund “Dear Leader” Kim Jong-Il supposedly shot 38-under-par (including five holes-in-one) the first time he ever played golf.

North Korea’s propaganda is outdone only by its military provocations, which over the years have included two assassination attempts on South Korean presidents, four large-scale invasion tunnels burrowed under the DMZ and countless small border skirmishes, kidnappings and commando invasions.

The most publicized incursion of recent years came in 1996, when a spy submarine from the North ran aground on South Korea’s east coast, resulting in a massive manhunt and fierce gun battles in the mountains of Kangwon Province. After this incident, the North Korean government issued a rare apology, promising that such a thing would never happen again. Last June, it happened again, in nearly the same location.

On this particular day, the North’s provocation of choice concerns an enormous underground construction site near the North Korean area of Kumchang. Government officials in Pyongyang insist the facility will be used for purely civilian purposes, but American officials are convinced it’s a nuclear weapons plant. Pyongyang is demanding a $300 million payment before it will allow inspectors onto the site.

If North Korea is indeed developing nuclear weapons, it will be in violation of the 1994 Geneva Agreed Framework, when Pyongyang pledged to freeze its nuclear program in exchange for two light-water nuclear reactors and interim fuel from the United States. But North Korea’s main bargaining chip has always been its seeming willingness to start a war that would kill tens of thousands of people and devastate the Korean peninsula. Amid tensions prior to the 1994 compromise, the U.S. nearly initiated the evacuation of 80,000 American civilians from South Korea. Whether the current impasse will require similar gestures remains to be seen.

At this moment, nuclear tensions are secondary to flashing cameras, as the last few members of my tour group pose for snapshots with the South Korean guards. After 10 minutes in the far end of the Military Armistice Commission building, this blue-walled slab of the communist North has begun to lose its novelty. I feel like the South Korean guards could just as well be wearing Donald Duck suits.

Spc. Vance, I notice, is glancing at his watch.

UNC Checkpoint Five offers us fresh air and a good view of the Bridge of No Return, where more than 12,000 prisoners of war were swapped in 1953.

Despite its ominous name, the Bridge of No Return looks downright bucolic. Were it not for the huge white North Korean propaganda signs erected Hollywood-style on the hills across the demarcation line, one might readily mistake the entire Joint Security Area for a Lutheran Youth Fellowship summer camp in rural Missouri.

Large white birds preen in the tall grass down the hill from the Checkpoint Five observation deck. Recent wildlife surveys have confirmed the existence of 146 species of rare animals and plants in the DMZ, including Siberian herons, kestrels, white-naped cranes and black-faced spoonbills. The untouched two-kilometer swath that separates North from South is the most pristine piece of property in this entire land, where population pressure has endangered 18 percent of all native vertebrate species. Foxes, roe deer, black swans, quail and pheasant thrive in the dense foliage. All animals large enough to set off a landmine, on the other hand, haven’t lived in the DMZ in decades.

This day is so foggy you can just barely make out the location of Taesong-dong, South Korea’s “Freedom Village” in the DMZ. Here, a handful of farmers make their living under strict regulations to be home from the fields by nightfall. The North’s DMZ village, called Kijong-dong, is uninhabited, and used primarily to blast propaganda and patriotic music at the South. At this moment, the loudspeakers of Kijong-dong are blaring what I assume are slogans praising Kim Jong-Il, but sound indistinguishable from the garbled entree clarifications one might hear at a Burger King drive-through window.

Spc. Vance tells us that the South Korean flag at Taesong-dong weighs 300 pounds and is hoisted on a 100-meter pole. Not to be outdone, the North Koreans have erected a 600-pound flag on a 160-meter pole at Kijong-dong. Someone makes the obligatory Freudian analogy and, as if on cue, the loudspeakers of Kijong-dong switch over to communist opera music so boisterous that it sounds like the score to a Monty Python movie.

For a moment, I slip into reverie at the absurdity of this grassy stretch of ground. The mood here seems downright extraterrestrial. Inspired, I ask Spc. Vance if we’re allowed to dance to the communist opera music.

There is an awkward moment before he realizes that I’m joking. It’s the first time I’ve seen fear in his eyes since the tour began.

The tourist circuit of the Korean DMZ ends at the Monastery, a combination beer hall/gift shop at Camp Bonifas. In keeping with the rest of the DMZ, the Monastery is appropriately weird: One corner houses a shrine to the victims of the 1976 Panmunjom Ax Murder Incident, another houses a bar and a third corner sports a perfume counter. In the course of 20 paces, one can buy Amore skin cream, quaff a Budweiser and peruse grainy black-and-white surveillance photographs of Capt. Arthur G. Bonifas and Lt. Mark T. Barrett getting hacked to death by a swarm of North Korean soldiers. T-shirts come in three colors. Visa and MasterCard are accepted.

Longing for one last look at the DMZ before we head back to Seoul, I duck out of the Monastery and walk out past the tour bus. I turn around and around in the road, but I have forgotten which way North Korea is.

It’s so quiet here, the only sound is the scrape of my footsteps.

I stop for a moment and reach into my bag for the DMZ commemorative key chain I got at the Monastery. I bought it in a moment of impulse, thinking perhaps there will come a day when I can shake my head and chuckle at the idea that this place ever existed.

This essay originally appeared in Salon on February 3, 1999.