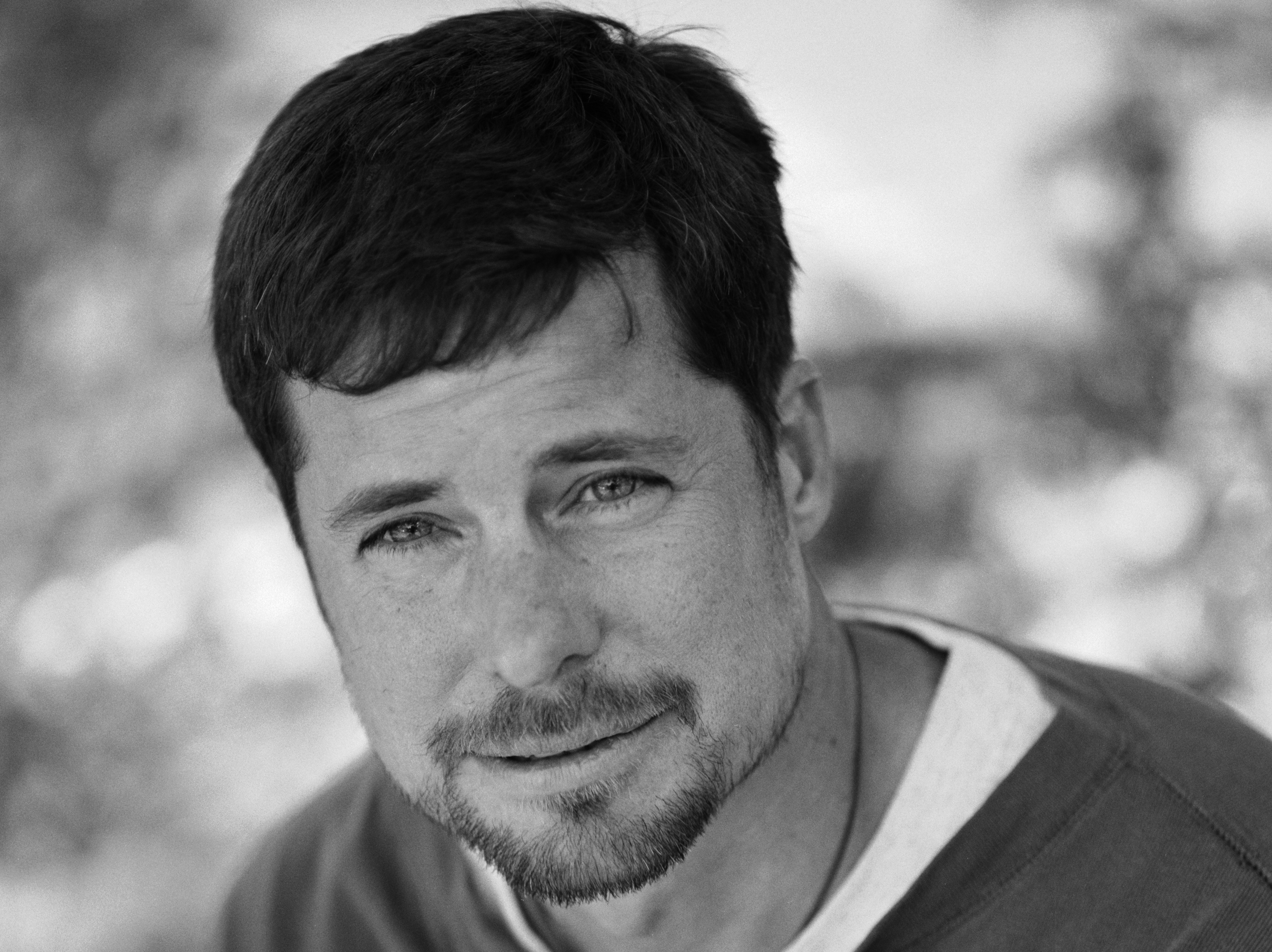

Kevin Fedarko has written for Outside, Esquire, National Geographic Adventure, and a trio of his adventure stories from the Himalayas, the Horn of Africa, and the Colorado River have been anthologized in The Best American Travel Writing. He studied political science at Columbia University and Russian history at Oxford before joining the staff at Time magazine, where he worked primarily on the foreign affairs desk. His first book, The Emerald Mile: The Epic Story of the Fastest Ride in History Through the Heart of the Grand Canyon, won a National Outdoor Book Award and the Reading the West Award, was a finalist for a PEN Literary Sports Writing award, was selected as the top pick of Southwest Books of the Year, and was a New York Times bestseller. Fedarko lives in Flagstaff and works as a part-time whitewater guide in the Grand Canyon.

How did you get started traveling?

I don’t actually think of myself as much of a traveler. My traveling resume, particularly in comparison with that of some really serious travel writers I know, is pretty limited. It sounds impressive on the surface because the range is somewhat extensive and includes places like Everest Base Camp and the Caucasus Mountains in the Republic of Georgia, and Djibouti in the Horn of Africa. But I’ve probably only been to seven or eight really cool and exotic places around the world. I’m not a professional traveler who is addicted to the magic and wonder and excitement of being on the move. In fact quite the opposite. I really loathe and detest jumping on and off of airplanes. I’m intimidated by moving from one culture to another, which I find very jarring. My instincts are to plant my feet in one place or one landscape and develop a relationship with it and come to know it at a fairly deep level. I’ve got a lot less Eric Newby in me and a lot more Wendell Berry.

But to the limited extent that I am a traveler, I suppose that process began in my senior year of high school when I headed off as an exchange student from my home in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Pune, India. I spent a year living there under the auspices of a Rotary International exchange program, which meant that among other things I was passed around between five or six different families, each of which was from a different religion, and each of which spoke a different mother tongue amongst themselves (they all spoke English to me, and I went to an English-speaking school). I was thrust into an experience of living abroad, with families that almost made it feel as if I was traveling to five or six different cultures within the same country during the course of that year. That was an enormously formative experience for me. Prior to that I think my only trip outside the country had been a trip with my parents to Niagara Falls. So it just kind of opened my eyes to the world beyond the parochial borders of what I knew as a boy in western Pennsylvania.

How did you get started writing?

By accident. I don’t remember writing stories as a boy, and I never wrote for my high school newspaper or my college newspaper. I bumbled into the profession by virtue of the fact that I emerged from graduate school at Oxford with a masters degree in Russian history and literature, and a piece of paper that said I was fluent in Russian. I was pretty far from fluent, but I was hired by Time magazine in New York. This was in the late-eighties, early nineties when the former Soviet Union was in the process of collapsing, and they needed somebody on their foreign desk who they thought could speak Russian. And so over the course of the next seven years I kind of moved up the ranks at Time, from a fact-checker and researcher to a staff writer, and eventually to a correspondent.

What do you consider your first “break” as a writer?

I suppose getting hired by Time with such embarrassingly thin and abysmally inadequate qualifications qualifies as a break. But there was another break, which was more of a self-made break. Back in those days Time Inc. had a policy (which would probably get them sued right now) of hiring young people as temporary staff. Every four months, I was fired and told to go off on a two-week unpaid leave, at the end of which I could come back and get re-hired. This was so that Time could avoid paying full-time benefits and treat people like myself as part-time employees.

On the first of what turned out to be several self-financed reporting trips, I went up to Newfoundland. At the time this was the poorest province in Canada, and its economy, which was dependent upon cod fishing in the North Atlantic, was in the process of collapsing. I went up there on my own dime and spent two weeks reporting the story, which my superiors were kind enough to publish in the pages of the magazine — and they asked me for another one after that. So that was my first real break as a writer.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

My biggest challenge is overcoming my own shyness and introversion. There’s a subset of writers who are wildly charismatic and preternaturally gregarious, and just sort of create a wonderful chemistry with people as they move through the world — and that throws off all sorts of sparks and opportunities in terms of things to write about. I’m pretty much the opposite. I’m shy and introverted and socially dysfunctional, and most comfortable staying at home by myself, reading a book written by somebody else. It’s always this hurdle that I have to get over when I’m in the field, of forcing myself to not disappear into a hotel room, but going out and meeting people and talking to them and acting against my own instincts.

Invariably it turns out that I have these wonderful experiences, and I wind up meeting these extraordinary people, and I come away refreshed and invigorated and inspired by these encounters. So it’s always a bit of a mystery to me why I’ve never learned the lesson that it will all be OK. But I never have, and so it’s a challenge that continuously arises. I have to start at ground zero every time I walk through the doors of an airport into another country and begin to fight against and overcome my own instincts not to talk to people.

What is your biggest challenge in the research and writing process?

I think the biggest challenge is figuring out how to control the information. By which I mean all of the information. The words that pour forth from the pages of the transcripts that my interviews generate. My own notes and observations. And then all of the data that comes flowing out of reading and doing research. That all comes together in the form of an unchained tiger that just sort of runs around the room unless it’s brought under control.

To invoke a metaphor that comes directly out of my book, it’s a lot like rowing whitewater, in the sense that every rapid presents a picture, at the top of it, of complete and total chaos. There are all these currents going different directions. There’s water and spray flying everywhere. And what you have to do to get through is to pick the clean line and discern a path through that chaos—one that avoids the obstacles and gets you to where you want to go. This often requires a series of deft maneuvers that have to be very carefully timed and well executed. For me, handling the tsunami of information that comes in the course of trying to get a book under control amounts to the same thing. And therein lies the biggest challenge for me: finding a clean line through the chaos of information.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint?

There would be three of them. Number one is money, number two is money, and number three is money. Money in all of its forms. Negotiating commissions for articles or advances for books that can sustain me for the period of time it takes me to do the work. Trying to convince magazine editors to pay for articles that were written six or nine months earlier. In general, just trying to keep the wheels from coming off. It’s a terrible way to make a living, from a purely financial standpoint.

Have you ever done other work to make ends meet?

Oddly enough, no. It seems as if, given how hard it is, that should have been the case. I think some of it comes from the fact that at least half of my writing career has been as a staffer at magazines — either Time or Outside magazine, as an editor, a guy with a salary. But it still strikes me as both astonishing and bizarre that I don’t have a side job moonlighting as the guy who sells used cars or vacuum cleaners or insurance policies.

What travel authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

Gosh, there’s so many of them. Somebody who stands out, who unfortunately is not nearly as well known as he should be, is a writer by the name of Eric Hansen, whose most enjoyable book is called Motoring with Mohammed. It offers a great model of how to construct an adventure and then incorporate research and background material that lifts the adventure to a higher plane, with both humility and humor.

Another one is a guy named Wells Tower — who’s probably better known for his fiction than he is for his travel writing, but his travel writing is just amazing. It doesn’t matter if he’s writing about a trip to Iceland or taking his aging father to Burning Man, it’s some of the funniest writing I’ve ever read in my life.

Finally, Tracy Ross and I have this two-person mutual admiration society that we’ve both been participating in for several years now. She thinks that I’m better than her, while I know that she’s better than me. And she either doesn’t know or is still trying to come to terms with the fact that she’s wrong and I’m right about that.

Some of the writers that I’m drawn to at the deepest level are writers whose work could only be considered travel writing if you really stretch the term, because they’re writing from a position that comes from having anchored themselves physically and metaphorically in a particular place or a particular landscape. A really good example would be Edward Abbey, who writes about all kinds of different places but never really leaves the one place he considers his truest home, which was the desert Southwest. It doesn’t matter whether he’s writing about the Colorado River running through the Grand Canyon, or the Black Rock Desert, or Organ Pipe National Monument—his sensibility, his use of language and his passion all derive directly from a continuous relationship with that landscape rather than a relationship that’s defined by parachuting into a particular place, spending a limited amount of time there, and then moving on.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

I have to say the first piece of advice I would invoke is “don’t do it!” It’s a terrible way to make a living, during an era when it seems as if writers are paid more poorly and worth less with every passing year.

For those who are determined to ignore that excellent and valuable counsel, I’m pulled in two completely contradictory directions. On the one hand, I’m tempted to say, look, we’re in the midst of a phase when the delivery vehicle for narrative is being fundamentally reinvented for the first time since Gutenberg came in with the printing press. We’re living in an era when it is now becoming not just advantageous but probably necessary and mandatory for anybody who wants to be a professional writer and journalist to master a skill-set that goes far beyond putting words on the page. One that encompasses everything from maintaining a sophisticated, multiplatform social media network where the storefront is always open, to — in addition to a notebook and pen — carrying a video camera and a cell phone that can deploy audio and pictures. And the ability to create, generate material for, and edit and disseminate videos. I sort of look at this world that I don’t really understand and I’m not really a part of, whose skills and technology have left me in the dust, and I’m tempted to tell anybody who wants to go into it, you need to learn not just how to master, but really enjoy those skills.

The oppose direction I’m pulled in is the advice of an aging dinosaur. The old-school adage is to stick to fundamentals, don’t be distracted by the whistles and bells that go with generating social media or putting cool pictures and videos on the web. The skills that are required to build raw narrative are very difficult to acquire. They require great diligence and time and discipline, as well as enormous investment in the sine qua non enterprise, without which nothing else is possible, which is reading. Reading, reading, reading — everything you can get your hands on.

I think the first category of advice is probably the smarter one. But the latter is what I rely on.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

In considering that question I’m reminded of an experience I had while I was traveling. I guess this would have happened in 1989, when I was in Leningrad, which is now St. Petersburg. I was invited to dinner at the apartment of a Russian scientist. Like all Russian scientists his range of interests went far beyond science. We fell into this conversation about Karelia, which is the region that runs along the border of Finland and Russia. It’s a beautiful area, and it’s an area that he had visited multiple times in his life, and to which I had never traveled. One of the things he said, which has stuck in my mind ever since, is that one of the greatest pleasures in life is not traveling to a new place, but returning to a place you’ve already been to, and doing so over and over again.

One of my great satisfactions is that I have picked subjects to write about that have required me to travel to them, but then have demanded that I keep coming back and returning to them. My relationship with those places — the most important of them right now being the Grand Canyon — has only grown deeper and more nuanced and more profound with repeated visits back. For me the delight and richness and appeal of travel resides not in what must be so attractive to so many of my colleagues — which is constantly going to new places and constantly experiencing new things, new colors, new languages, new sounds, new landscapes — but in going deep rather than going broad, and by traveling in a way that is more of a loop than a line. I would say, emphatically, that the greatest satisfactions that I’ve had from my work come from traveling in circles.