By Irvin S. Cobb

I.

From time to time, as I stated in a preceding booklet of this series, it is customary for Bill Al White to strum his typewriter and burst into rhapsody on the merits of his State.

“I shall sing a few stanzas

A-touchin’ on Kansas,”

he cries, or ringing words to that effect. And does. And does it well, too—so well that, as you read after him, you decide you’ll go out there some of these days when you’ve been everywhere else and give Bill Al’s beloved land the friendly once-over.

So you go. You behold it in its wealth of unromantic horizontalitudenessities. You view its towns, which all of them are not altogether beautiful, and its sunflowers, which in mass grow monotonous—because, say what you will, when you’ve seen one sunflower, you’ve seen ‘ern all—and its rivers, which incline to muddiness and sandbars.

You look for the fabled grasshopper whose saw-fretted hind legs once fiddled a raspy requiem for the Kansas wheat, but learn that he, even as the buffalo which also once roamed these plains in countless hosts, has become practically an extinct species, alas.

You keep an eye peeled for one of those characteristic Kansas cyclones, but likewise in vain; for cyclones are out of vogue. The really important ones seemed to lose interest after Art Capper began offering such spirited competition. So now they are storing spare parts for the Ford and old subscription copies of the Life of William Lloyd Garrison in the former cyclone cellar, and the husbandman no longer gets a permanent wave in his neck from regarding the summer heavens.

You visit the historic place: Place where visiting Missourians abolished a batch of Abolitionists. Place where old John Brown turned right around and eliminated a few pro-slaveryites. Place where Aunt Carrie Nation, with the words: “I may not be able to tell a lie but, by francesewillard, I can tell a speak-easy as far as I can smell it!” took her little hatchet and chopped down the cherry bounce. Place where Sockless Jerry Simpson first took ’em off, or first put ’em on, I forget which. lace where Senator Peffer got his whiskers caught in the clothes-wringer.

You figure then that you have observed all of it that there is to be observed and to yourself you say:

“So this is Kansas, is it? Well, from this time on I can take my Kansas or I can leave it alone—and undoubtedly will! I am pre-pared to believe what these local enthusiasts tell me about the number of party telephone lines in the average county and about the size of their bank deposits.

“It naturally would be a great country for listening in and besides, what could these people do with their money except save it? But still, there can’t be as many trains leaving here for outside points as they let on, or practically everybody would have got away before now. Emporia and Atchison, a long farewell! Topeka, take a good look at me now because this is positively going to be your last chance! Dodge City, the man who named you meant it as a warning! Abilene, adios!”

That is what you are apt to say, especially if, naming no names, you hail from that metropolis of the Eastern Fringe where we have the largest number of visible sky-scrapers and the fewest number of visible sky-pilots. The truth of the matter is, though, that you haven’t seen Kansas yet. You merely have skimmed the surface, which is easy to skim, being flat the way it is. In a sketchy sort of fashion you’ve looked the country over, but you haven’t met Bill Al’s kind of folks—Walt Mason and Ole Ed Howe and Hen Allen and Vie Mur-dock and the rest of the real people.

Maybe you are so lucky as to be introduced to these heads of leading families. Perhaps you get a chance to go around some with Walt, which is easier on a hot day than trying to go ’round him—Walt being, since he fleshened up so, what you might call a Human Detour—and maybe, too, you talk with Ole Ed or you watch Hen politically functioning, which he certainly can film- -Lion once he gets started, or hear the vocal twenty-ball Roman candle that Vie is, when in action. If so, you revise your earlier judgments, for you have made the discovery that while this State may be a trifle shy on natural beauties she has plenty of mental Alps and moral Himalayas to compensate for what was left out of the mixture when the original plan of creation was being thought up.

And in the ancient verity that it is not so much how a country appears to the casual eye as what it can produce in men and intellect and progressive legislation and for-ward-thinking and right-living and educational advancement and prosperity-building, you find much food for thought as you start back for West Two Hundred and Twenty-seventh Street, overlooking the Subway. I know I did.

II.

I am thinking now of the occasion when I first began to know Kansas. We had met before but we had not been regularly introduced. Slantwise, I had crossed the State hurriedly and glad of it—on the way to the Pacific Coast; but nobody ever yet saw a country from a car window. You might just as well expect to learn the science of electricity from watching an electric fan buzz around. To me, moving along swiftly, Kansas seemed a dismalish interlude be-tween the Mississippi Bottoms and the Raton Pass, a sort of dull-toned anteroom through which you must pass to reach the wide sun parlors of New Mexico and the great corridor of painted glory that is Arizona.

So, when fate, personated by the booking agency of a lyceum bureau, decreed that I should jump out of the Teutonic comforts of St. Louis clear over to a smallish community of interior Kansas, there to emit my little piece from an opera-house stage, I went with no noticeable uplifting of the spirit. To tell you the truth, it made me feel as bored as a circus lion, than which there’s nothing on this earth border.

It was in the month of March. It was in the middle of a tempestuous and fickle March and the way Winter lingered in the lap of Spring was something scandalous. This is the time of the year when the Wheat Belt is at its very lowest pitch, so far as its appearance goes. By night the earth freezes and by day it thaws, so that the soil is a boggy, sticky compost and the weather is never the same two days in succession. Hail—as the poet says—hail, Gentle Spring, and sometimes rain or snow.

To reach my appointed destination I had to quit the main line soon after breakfast and, after a weary wait at a junction, take an accommodation, as some practical joker has named it, over a winding and bumpy branch road which appeared to have no more sense of direction than an egg-beater. It was one of those branch roads on which the through passengers make pools on the day’s run, and its train schedule was the work of a born humorist. In the middle of a raw, chill afternoon, two hours and forty minutes be-hind time, I climbed off my day coach at a point far out in the sloshy hinterlands.

Kansas was up to its hocks in a mud batter. The station was as homely and shabby and unfurnished as the average small-town station is; if anything, that station was more so. I learned that housing accommodations for the alien were at a premium here; there was some sort of convention going on. So I took what I could get. The hotel to which I was directed was not the largest hotel in the town—there were two others of relatively greater size—but undoubtedly it was the one where the most suicides took place.

Filled with wonder that any group of persons should choose to hold a convention at this season of the year and that they should pick on this town as a place for holding it, I jammed myself and my hand-baggage into a misses-and-children’s size jitney and told the driver where I desired to go. We went, careening over the half-congealed, half-molten ridges, thence splashing down into yellow puddles and thus along a main street of uninteresting-looking houses to an angu-lar structure which, as I found out later, had been condemned by everybody who’d ever entered it except the local building inspector.

III.

Right here, I think, would be a good place for me to say that in the opinion of this somewhat seasoned tourist the best advertisement any small American community can have is a decently-appointed and well-served hotel. The stranger may for-get your proposed Civic Center or your plans for a Great White Way, for he has encountered such ambitious undertakings elsewhere on his travels but if at your leading hotel he badly was bedded and poorly was baited he will remember your town for-ever after as a spot to be cursed and avoided.

The local philanthropist who builds for you your public library might have left a more satisfactory monument to his memory and good deeds had he endowed a public hostelry. If he did no more than found al fund for the proper cleansing of the table-ware and the proper airing of the guests’ coverlids, that would help. On the food side we probably have worse small-town hotels in America than any other civilized country. has. And the Kansas average is as deplorably bad as the average is in the States which surround her. And this particular one notably was bad.

As I wriggled out of the snug conveyance which had brought me here, my hat caught on the door-jamb and was pulled off, brushing my face as it fell. With a dexterous gesture I caught it in mid-flight and clapped it back where it belonged, then, with a whoop of agony snatched it away again and pressed my two hands to the peak of my skull. I was on fire. The hair up there was singed from a space as large as a silver dime and where the hair had been was a throbbing blister. By some freak of unwitting legerdemain I had, in retrieving the truant hat, neatly knocked the live spark off the tip of my cigar and caught it in the crown of the hat from whence it had been transferred, a red and glowing ember, to the top of my head. To do the thing intentionally, only a professional juggler would have been competent and he would have hesitated, I think, unless he had an asbestos scalp.

The ruins were still smoking and I had a caressing palm pressed to the recent site, which hurt like the very mischief, as I entered the hotel. Its interior lived up to its outside promises; it was terrible. The office was a tightly bottled retort for the preservation of an assortment of menagerie smells. Quite a large number of flies had wintered there; thus early there was ample guarantee of a sufficient supply for summer. Some were buzzing cheerily against the specked window-panes. I knew where I would find the despondent ones. The mustard cruet in the dining-room beyond would be the mausoleum for the mortal remains of those suicides. It always is.

IV.

Having registered under the eye II of the proprietor or fly-master, I mounted creaking steps to the second floor and traversed a moldy corridor haunted by the ghosts of some very bad cabbages that had died and gone to Hell and been condemned for their sins to fry eternally. In an alcove in the hallway, right next to the room which had been assigned to me, an ancient battered piano was crouched in the shadows, showing its yellowed teeth like a crabbed alligator; and on a stool at this piano sat a fat lumpy little girl, practicing on it no, there’s a better word. She was preying on it.

I was ushered into a chamber where the aroma of rotted oilcloth contended with the perfume of a leaky gas fixture. They were running a dead heat for second place behind the cabbages but nobody could say they both weren’t trying. The bed was one of those beds which an East Indian fakir preferably would stretch upon if he couldn’t find any thorns handy, or a pallet of iron chains. It was high at the sides and sagged in the middle, and through the flimsy mattress I could see the uplifted shapes of the springs where they were coiled to strike. The sheets had plainly not been washed for quite a spell; I doubted whether they had even been searched.

On numerous counts I was out of sorts. For one thing I was tired. My burnt district still gave much pain. I was drowsy. The night before, on the Pullman, the Swiss yodeler who occupied the berth just across from mine kept rehearsing in his sleep. I strongly felt the need of a nap; if slumber could knit up the raveled sleeve of care this would be a swell chance for her to do her stuff.

I cast myself upon the bed and the loosened head of the springs struck back and fanged me in the short ribs. Curious unclassified noises kept filtering in through the thin partition wall. The ragged shade slatted and chattered where the wind came in by a gap in the window; and the young instrumentalist outside the door was without mercy. She ran the scales more than two hundred thousand times—I kept count up to the one hundred and ninety-thousandth time—and then, after many efforts, she succeeded in striking an octave. She was a pudgy little thing and I think the only way she could strike an octave was by turning around and sitting down violently on the keys. Anyhow, that was how it sounded. Having mastered the feat she kept repeating it. I seemed to hear her gladly bouncing herself up and down and the piano-wires twanged and I was the widest-awake party or the wide-awakest—as the grammar of the case may be—in that part of the Union. I lay there and suffered and called the State of Kansas hard and unforgivable names.

V.

There came a knock at the door and I bade whoever was there to come on in. I rather hoped it might be the manager of the opera-house, whom already I had met, t. coming to tell me his o era-house had burned up or fallen apart or something, in which event I would re-pack my bags and hurry right down to the depot and catch the first train leaving in any general direction.

No such luck. The man who entered was a stranger to me. He was small, quietly- dressed, unimportant-looking. And he was smoking one of the most violent and unruly cigars I ever saw in my whole life. Every now and then it would get entirely out of control and back-fire on him and spew his front with ashes and clinkers. I groaned inwardly. At first appearances, the stranger had the look about him of being a bore. Through bitter experience I had learned that in every town is at least one official pest craving to decant his windy commonplaces upon any visitor whose name he has at one time or another seen in print; probably this person held the job in this community.

We shook hands and he told me his name, which sounded like Wyhrxz, the same as nearly all names sound the first time you hear them; and he said he was an office- holder there, but did not state what office it was, but just let it go at that ; and he went on to say that he had been chosen by the local committee to present me to this coming evening’s audience and, then, between fits of contending with his back-draft, he talked to me and with me about things in general.

And how the man could talk! He had read everything worth while that ever been written by anybody worth while. He had been about and he had seen things and could express himself graphically and humorously on what he had seen.

He had views on men and matters, on causes and events, and they were not borrowed, second-handed predigested views out of somebody’s loan collection, either; not foundlings that had been left on the door-step and adopted by him as his own. They were crisp and vivid and witty and picturesque, and he was their father and their mother, or I missed my guess. He wasn’t bumptious or dogmatic or cocksure or opinionated. He just was one of those rare creatures who know what they are talking about and know how to talk about it.

Presently he checked himself to remark upon the fact that I was not smoking and yet, as he said, all the pictures he ever had seen of me showed me with a cigar in m mouth. He insisted that I take one of his. I had half a thought to tell him that, while I smoked, I didn’t countenance committing arson on strange premises, and I meant to add that anyway, something which recently happened led me to believe that the tobacco habit was dangerous: it caused loss of hair.

But the fascination of the man’s personality held me in its spell and I yielded and took the sinister long black roll which he brought forth from a breast pocket where he had a stock of them binned. He said, with a touch of local pride in his tone, that this cigar was of strictly domestic manufacture—made right here in town. But that was unnecessary. One felt instinctively that the Interstate Commerce Commission would prevent the shipment of this brand to or from outside points. He told me its name which I have forgotten—perhaps it was The Burning Shame.

Anyway, I lit it and it had a defective flue probably a family failing and pretty soon I also looked as though I had been cleaning out an anthracite stove. But I didn’t mind; I smoked the deadly thing right down to the water’s edge. For I was in contact with one of the sprightliest minds I’ve ever run into, anywhere. He stayed on for nearly two hours and when finally he left I was sorry to see him go.

VI.

After he had gone, I went downstairs and asked the clerk who my caller was, or rather, what he was ; I recalled that he had said something about holding office.

“Oh, him?” said the clerk. “He’s our county superintendent of schools.”

A county superintendent of schools, mind you!

“Well,” I said to myself, “you people here must not be able to recognize talent when you meet it. Where that fellow belongs is in the United States Senate. Hold on, that’s wrong he’s got too many brains for the Senate; most of the other members would be distressed and confused in his presence. He belongs in the White House that’s where. No, wrong again. If he were President we would hand-shake him and back-platform him and button hole him and j speech-make him to death, just as we’ve done to so many of our Presidents and that would be a national loss. I guess he belongs where he is. Judging by the looks of the town, there’s need for one good, full-dime sinned, original intellect in these parts.

Behold, how once more was I in error. only goes to show that you cannot judge a fruit by its outer husk. Came along 8:30 that night and this man introduced me—-in a mercifully short, unmercifully whimsical speech—to as live an audience as ever I have faced. A man who does much public speaking gets so, in time, that he senses the temper of a crowd the moment, almost, he claps eyes on it. I could get the mental heft of this crowd before my sponsor uttered a dozen words, and I grew abashed at the prospect before me.

It was by no means a citified audience. I didn’t see a single pair of spats the whole evening. Either the spat influence, originating abroad and working its way steadily westward from the Atlantic seaboard, had failed to penetrate this isolated district or else these people here felt as I did—that the main trouble with wearing spats in our climate is that, about the time you begin to quit being self-conscious, the weather starts turning warm on you. Although this was the year when the streamline forehead first became so popular in our larger cities, nearly every girl present seemed still to have all the eyebrows with which her Creator originally endowed her. And I had the conviction that should one of these matrons complain that her bridge was very bad this spring she would be blaming her dentist and not Elwell or Foster.

At the same time, it was not a countrified audience. If no spats offered themselves to my notice as I stood up to get under way, neither did my eye catch the gleam of celluloid cuffs nor my ear detect the rattle of the above. Here revealed itself an assemblage alert, responsive, cordial, sympathetic, electric. These people were generously appreciative of any poor efforts. They caught my points without any muffing, and not on the second bounce, either; they took ’em, as ‘twerp, on the fly. Their attitude made me regardful for my grammar which, like my spelling, naturally is of the Cubist school, made me remorseful for the feebleness of my memorized flights of philosophy. I had a horrid fear that a swine was casting itself before pearls.

But they bore with me kindly and when the spouting was over and I met some of the individual members of my late audience, I met none who was a slug-wit, none who visibly suffered from that somewhat common disease which might be called nervous culture. It was not a selected group that I met, mark you, but merely the random and casual run of the citizens of this town and, without exception, made up of flavory, savory at-tractive American types. It dawned on me then that my incendiary friend of the after-noon was no isolated phenomenon occurring in a waste of cultural stagnation, but that, intellectually, he was of a piece with the common pattern of his constituents.

VII.

Right there, in the wings of that shabby little hall, I revised my earlier impressions of Kansas and to this day I’ve had no occasion to change back. On further acquaintance and, in a balmier month, I have fallen in love with the wistful lonely beauty of the wide, flowered reaches of her prairie and with the glory of her sunsets, and I have tasted the sweet tang in her air when the little breezes that spring up after the sun goes down in the early autumn evenings come blowing over the shorn farmlands.

Likewise I flatter myself that, at long distance and in some small degree, I have absorbed an appreciation for the spirit of neighborly tolerance which inspires the humorous personal journalism it’s always humorous and sometimes very, very personal —in such papers as the Emporia Gazette, for the profound love of country which glows, like burning coals in a brazier, be-tween the bars of some of Gene Ware’s verses, for the muse which moves Walt Mason, for the straight-thinking behind the essays of Ed Howe, for the kindly under-standing of American virtues and American short-comings which reveals itself in chapter after chapter of Allen’s own book “A Certain Rich Man.”

And to myself I have said: “Some of these days a great poet will arise in this flat place a poet competent to interpret the real story of the land. And some of these days, too, an artist will be bred up who’ll evolve a type of architecture fitted for the plains and springing out of them, and then these towns here will be lovely where now they are homely when they’re not actually grotesque.”

VIII.

Speaking as a friendly onlooker and confessing myself subject to correction, it seems to me the history of Kansas, first as territory and then as commonwealth, falls naturally into three periods.

To start with, she was the thorn in the paw of the Slavery lion. On her young soil the juices of partisan antagonism which Massachusetts and South Carolina had distilled were stewed in a witches’ cauldron out of which came boiling the sour brews of two irreconcilable fanaticisms, one distillation as insoluble to reasoning as the other.

She knew the labor pains of civil war long before the guns firing on Fort Sumter announced the baptism of that hideous off-spring of intolerance mated to sectionalism. This was the Union’s child of trouble, conceived in the travail of a bitter feud, born in the dripping red bedchamber of battle, christened with the laying-on of armed and bloodied hands.

So much for her beginnings. In her second age, hers was a forlorn and lamentable state. For she came to be a byword of the wagsters, and at mention of the very name there ensued the laughter of fools which is like unto the crackling of thorns under a pot.

In the monologist’s repertoire she held that place among the States which, later, the Erie held among the railroads and later still, the Ford car held among the automobiles. According to the cruel and unpitying humor of the times, she was painted as the gawky product of an Abolitionist sire and an Agrarian dame—the dour face of a Puritan, the long, inquiring snout of a Pilgrim Father, the billy-goat beard of a Populist, a thumbed Old Testament under one arm, a rusty Jayhawker’s rifle under the other, shirt-tail out and toes turned in.

When you thought of Kansas you thought of mortgages, overlapping like the shingles on the roof; you thought of grasshoppers and windstorms and weird legislation and strange unhallowed political experimentation; you thought of whirling dustclouds and sun-blasted grain fields; of freak statesmen; of clodhoppers playing at leadership and clowns masquerading as crusaders.

Oh-h-h, the roosters lay eggs,

And they’ve feathers on their legs,

And they feed ‘ern on shoe-pegs—

In Kansas!

She was the nation’s standing joke, that’s what Kansas was then.

But not any more and not for quite some time past, in case anybody should ask you. Today this wellwisher envisages her as the prime embodiment of a reasonably successful effort on the part of the whole people to answer that question which Adam’s murdering son asked of his Jehovah. There are sundry States which insist on minding their own affairs and on not allowing any outsider to do any part of the minding for them; thereby have some of these States suffered, becoming narrow and provincial and backward.

There is at least one State which, speaking through her lawgivers and her law-enforcers, has resolutely and persistently undertaken to attend to the other fellow’s business, and that State is Kansas. It has been her way to shape out original and sometimes curious plans of governmental operation, to frame drastic laws of ministration and administration having behind them no model of precedent or tradition, and then to keep projecting with them and tinkering at them and fiddling at the inner works of them, until these revolutionary mechanisms did the bidding of their daring designers and, more than that, gave satisfaction to the public at large.

In setting up Prohibition as a statewise ordinance, Maine pointed out a path but, having copied the plan and with the force of localized public opinion for her main weapon, Kansas enforced this law within her own borders long before there was an Eighteenth Amendment to give Constitutional force and Federal strength to the letter of the mandate, while, as for Maine well, still and yet, even in these Volsteadian days, Maine, she says it with hiccoughs!

“Here’sh lookin’ at you—double,” murmurs Maine, and lifts the forbidden noggin filled with befogging stuff smuggled across the boundary. And New York and Rhode Island and Jersey and most of the others drink the toast. Not so with Kansas, wearing a dornick chipped from Plymouth Rock for a watch-charm—not so’s you’d notice it! She rams compulsory temperance down the throats of her children and makes ’em like it, and they lick the spoon and cry for more.

Because—and here’s proof that a virtue overdone may become a vice—because the typical Kansan is over-ready to write pedagogic legislation into the statute book and over-docile to obey it once it is written there, wherein he somewhat differs from the rest of us. There is a common tendency among us to pass more laws and yet more, rather than to demand enforcement of those laws which already we have. But the Kansan takes ’em and obeys ’em as they come. And this habit, ingrained in him, has its tendency ness and the physical ugliness of the com- munity life about him. If he has one out- standing fault I’d say that fault is the fault of smugness. A schoolmasterish instinct is in him.

IX.

It was Kansas, that pioneer into un- tracked fields of sumptuary legislation, which enacted a law against cigarettes; their use, sale, loan and gift. And wasn’t it within the halls of her state capitol where some in- spired solon from the tall grass offered the bill requiring that tavern and boardinghouse bed-sheets must be of sufficient longitude to cover the longest guest up to his—or her—chin line? Or was it in Oklahoma this came to pass? On second thought, it must have been Oklahoma. Your true Kansas reformer would have framed an enactment to saw off the legs of the patron to proper length.

It might be said—and said with some color of truth, too—that in her forward march toward special righteousness and common betterment, Kansas has pressed into the dust the ancient right of private selection on the part of the individual as to his private conduct, and left it lying there, flat and dead as a squashed tumble-bug. Those who steer this Chariot of Fire, with its water-wagon trailer, would answer back that there’s no such thing as personal liberty where it runs counter to the will of the masses—that the theory of the greater good to the greater number outweighs such petty considerations as to the wishes of any isolated human insect who thinks against the current instead of with it.

“See this?” proclaims the voice of the militant majority to the rebel, “Well, this is the Golden Rule and we’re the boys that know how to apply it. Now then, will you take it nice and quietly or must we apply it to the seat of your pants until we’ve just naturally fanned All the nap off?”

Call her a Meddlesome Mattie, if so be it pleases you; call her a Peeping Tom, with a holier-than-thou gleam in a searching eye, a Paul Pry with a greedy ear pressed against the next-door keyhole, a Nosey Parker whose proboscis is forever sniffing out hidden evil, a latter-day Witch-Finder, hungry for fresh victims, a Nineteenth Century Inquisitioner constantly on the hunt for dissenters and heretics and Protestants against her prevalent parochial dogmas. On all counts of the indictments, Kansas would plead guilty and rest the case for the defense upon this record, namely, to wit, as follows:

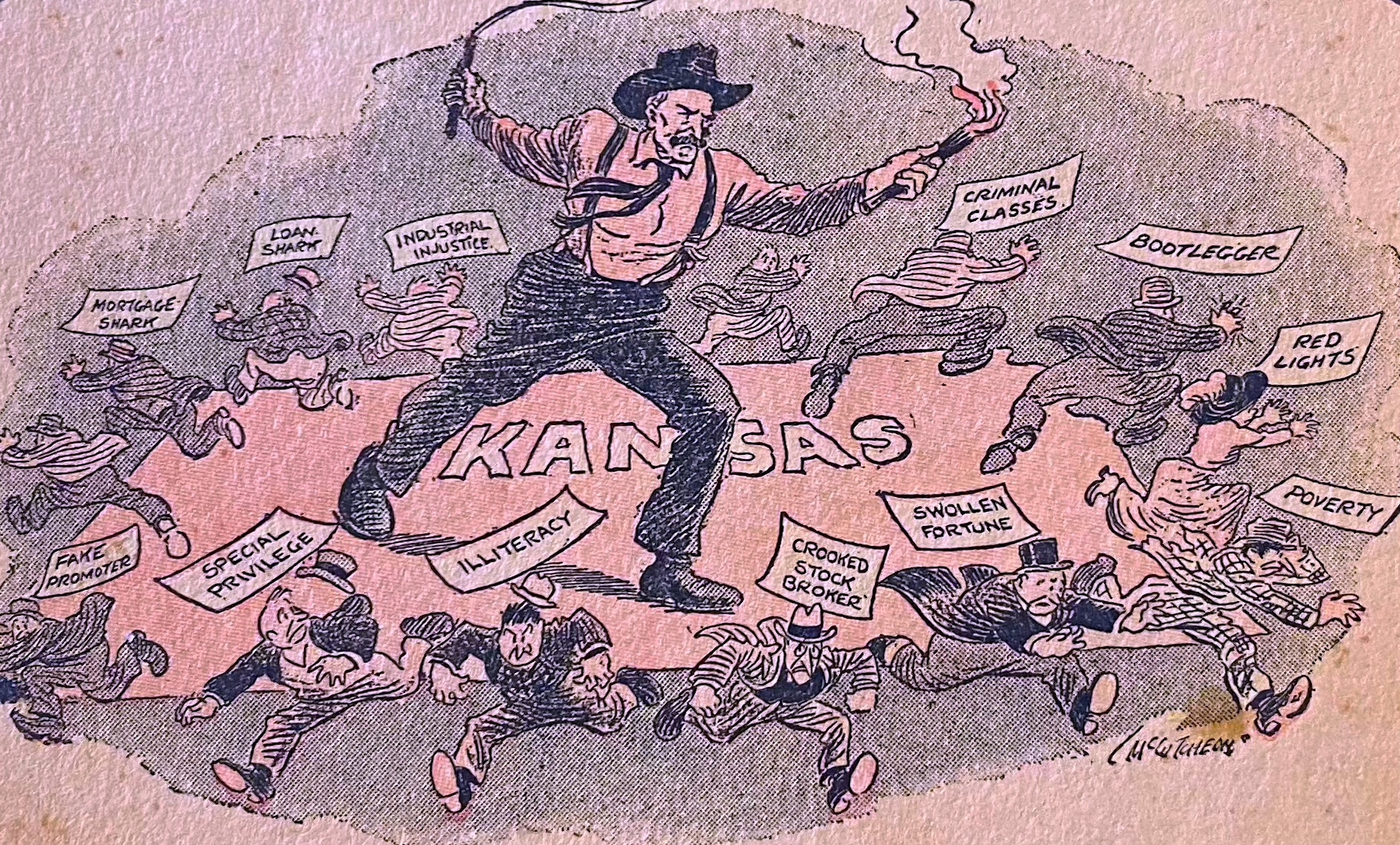

That she has pried and meddled and probed and eavesdropped with most whole- some effect upon the moral and material health of the commonwealth; that she has contended, more or less availingly, with the social evil; has promoted industrial jus- tice ; has stabilized and adjusted interior economic forces has formed an enduring governmental partnership with the higher moralities; has so wrought that now her professional criminal class is negligible and a pauper class practically no longer exists; has so wisely distributed her wealth—divided it, rather—that swollen fortunes are rare and poorhouses aren’t needed; has curbed the dishonest stockbroker and put hobbles on the speculative custodian of invested or deposited savings has shaped her people into as orderly, as godly, as uniformly prosperous, as well-content, as patriotic and most noteworthy perhaps of all as generally educated a mass of citizenry as is to be found inhabiting any State of the Union.

Finally, now and then she has given to the nation a quality of political leadership which amply reflects the radical, progressive, corrective, inquisitive, remedicial, experimental spirit which is the very soul of this new Kansas of the third period—the Kansas which cries out so loudly that all the peoples of the Nation may hear:

“Am I my Brother’s Keeper? You bet your sweet life I am!”

Postscript

Cobb’s America Guyed Books

To see the laughable side of American life and to see as well the fine sturdy qualities that make the States of the Union as distinct as human beings is Cobb’s unusual achievement in these books.

Beneath a humorous surface of good-natured joshing one finds the State and its people, their peculiarities and time-honored traditions.

You will find much amusement in these books and a fresh point of view. They are eminently good to read and the best sort of souvenir to send a friend. Don’t miss any of them. These volumes are now ready:

NEW YORK: So far as I know, General U. S. Grant is the only permanent resident.

KANSAS: A trifle shy on natural beauties, but plenty of mental Alps and moral Himalayas.

INDIANA: The middle layer of perhaps the noblest slice of earthly cake.

MAINE Great singers are made by contending with the words in the Maine geography.

NORTH CAROLINA: A state most people have a sleeping-car knowledge of.

KENTUCKY: From center to circumference, from crupper to hame, from pit to dome, a Kentuckian is all Kentuckian.

Other volumes in preparation. Fifty cents each.