I might never have learned about Johnnie Wadie Red Tabel had it not been for Mustafa, a chubby-faced guy in his mid-twenties who worked as a tourist hustler in the various backpacker hotels near Cairo’s Orabi Square.

Mustafa’s career hinged on the refined tastes of middle-class Cairenes, who were willing to pay him inflated prices for the fancy imported liquor brands—Gordon’s Gin, Finlandia Vodka, Johnny Walker Whisky—that were usually only available at duty-free stores. Since all tourists arriving in Egypt were allowed a 48-hour window to buy as many as three liters of duty-free spirits, Mustafa’s job was to find freshly arrived foreigners—people like myself—who were willing to acquire booze on his behalf. Not long after checking into a grotty dive called the Sultan Hotel, I picked up two bottles of Rémy Martin Cognac for Mustafa’s clients, and one bottle of Four Roses Bourbon for myself.

The bourbon proved a useful asset in meeting people at the Sultan, where an international array of young travelers socialized in the lobby each evening under kitschy Day-Glo wall paintings of Pharaonic gods and camels. After my first night I’d made plenty of new backpacker friends, but I’d run out of bourbon, so I tracked down Mustafa. He led me on a fifteen-minute trek to a dumpy domestic liquor store in an alleyway near Talaat Harb. “You have seen the duty-free store,” he said. “Now you will learn what it is like to drink like an Egyptian.”

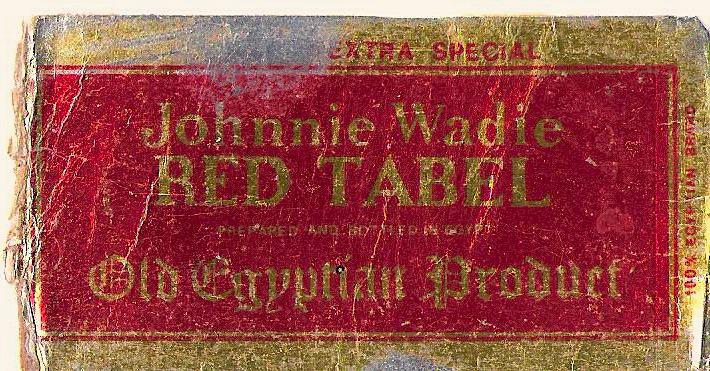

Though drinking is generally frowned upon in Islamic societies, Egyptians are allowed to purchase domestically produced alcohol at government-approved stores. The Talaat Harb liquor retailer sold several brands of locally brewed beer, including a decent lager called Stella and a potent malt liquor called Sakara King. Domestic spirits were a sketchier prospect, as the selection was limited to dubious knockoff brands like “Fineland Vodka” and “Gordoon’s Gin.” After a bit of banter with the storeowner, I left with a liter of “Johnnie Wadie Red Tabel.”

Mustafa declined an offer join me for a drink, but—since ironic cross-cultural boozing is a time-honored hallmark of backpacker culture—my bottle of fake Johnny Walker proved popular at the Sultan. Whatever Johnny Wadie Red Tabel was, it wasn’t whisky; its flavor was a medicinal blend of anise, vanilla, and laundry detergent, and its buzz arrived in tandem with its hangover. Four fellow travelers and I had nearly polished off the bottle while sitting on couches under the murals in the hotel lobby when a Dutch guy paged through his Lonely Planet and recited a passage about how the Canadian embassy had issued a circular advising its citizens against drinking Egyptian whisky due to unspecified health concerns. “Leave this stuff well alone,” it warned.

For moment none of us said anything. Then, marveling at how dramatic the occasion had suddenly become, we raised our glasses, made a toast to the quirky pleasures of Egypt, and took our lives into our own hands.