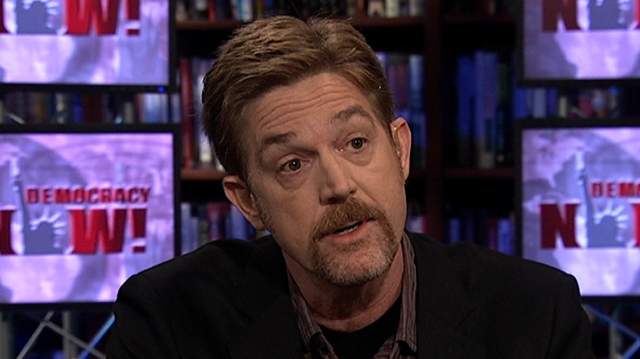

Jeff Biggers has worked as a writer, radio correspondent, and educator across the United States, Europe, Mexico, and India. He presently divides his time between Illinois and Italy. Winner of the American Book Award and a Lowell Thomas Award for Travel Journalism, he is the author of In the Sierra Madre, and The United States of Appalachia : How Southern Mountaineers Brought Independence, Culture, and Enlightenment to America. For more information, visit www.jeffbiggers.com.

How did you get started traveling?

I grew up in a family that traveled and moved a lot, changed cultures. I cashed in my baseball card collection and bought an airplane ticket to New Zealand a few days after I graduated from high school and never looked back.

How did you get started writing?

I think my first article was for a college newspaper, the Daily Cal in Berkeley. But I dropped out of college and started hitchhiking across the country, ending up in Appalachia. Over the years, as I drifted from the East Coast to Latin America to Europe and elsewhere, the stories started to write themselves, in various forms, from journalism, history to poetry, fiction. I consider myself a traveling writer.

What do you consider your first “break” as a writer?

In terms of travel writing, I found a lot of doors opened after I published a couple of pieces on Mexico and Italy in The Atlantic Monthly Online, and started contributing regularly to PRI’s Savvy Traveler radio program.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

As part of my journalism training, I have always been worried about getting the facts right. About taking the time to listen and observe. Getting beyond front door observations. Appalachia taught me a lot about the danger of outside travelers in perpetuating misinformation; few regions in the world have been so maligned by travel writers more interested in a quick and dirty piece rife with stereotypes. Married to an Italian citizen, having lived on and off in Italy since 1989, which is one of the most popular destinations for travelers and travel writers, I see some similar patterns of writing here. If I get the story wrong in this country, I have to deal with my in-laws.

What is your biggest challenge in the research and writing process?

I’ll give you an example: I am working on a book right now about a couple of trips to India, about discovering an extraordinary community of so-called “untouchables” and tribal peoples in a once deforested area that has now bloomed into a self-sufficient and thriving tropical forest village. It’s one of the most beautiful, fascinating, hopeful places on the planet. I spent months collecting interviews, pouring through decades-old documents crusted by white ants in palm-leaf huts, traipsing the back trails into the mountains and jungles, but I am still struggling to find the right narrative voice to make this story — and its history — come alive to a broad, outside readership.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint? Editors? Finances? Promotion?

As you know well, much of the travel narrative book market is beholden to narrow slots. The slot for so-called literary travel writing is even narrower. One editor once told me: Either give me silly and irreverent, or give me deathly adventure. He obviously doesn’t travel much; probably hasn’t changed his haircut since 1975. I think there are a lot of readers out there who want more; who hunger for those unusual, wild, informed, truly funny and astonishing stories beyond the canyon walls, or down the back warrens, that are still waiting to be discovered. I think it’s important for those of us who love this genre, who love to travel, to keep pushing editors and publishers to widen the doors for diverse types of travel writing.

Have you ever done other work to make ends meet?

I doubt my writing will ever make ends meet, so I’ve picked up jobs along the way: a limo driver in New York City, farm hand in the South, sports coach in Switzerland, community organizer, cook, teacher, musician, etc.

What travel authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

So many great travel writers, including yourself, remind me that the genre is alive and well. I read different books and articles for different reasons. I love historical travel memoirs, dating back to Cabeza de Vaca’s chronicle of his wander across North America in the 1530s, or the huge treasury during the golden age of travel writing in the late 19th century, like Frederick Schwatka’s mythomaniac memoir about the Sierra Madre, In the Land of Cliff and Cave Dwellers. I appreciate novelists and poets who break from their treadmill to write about their travels, such as Andre Gide’s Travels in the Congo, Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad or Michael Ondaatje’s Running in the Family. I often reread the contemporary masters, such as William Least Heat Moon, Colin Thubron, Jonathan Raban, Jan Morris — they show us how great travelers become great story tellers. I admire the work of a lot of younger writers, such as Tom Bissell, Peter Hessler, Jeffrey Tayler and stalwarts like Barry Lopez, Tom Miller, Sarah Wheeler. I think Beryl Markham’s West With the Night, about her sojourn in Africa, is one of the most breath-taking travel books ever written. I reread Bruce Chatwin’s Songlines every year, if only to remind myself about the beauty of wandering, and the possibilities for putting it into words.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

Do your homework, travel locally and know your own cultures and heritage like the back of your hand, learn languages, read a lot of history, read a lot of foreign novels, watch a lot of foreign movies, write about what you love with a sense of passion and purpose, don’t worry about getting published until you’ve learned the craft, and if at all possible, marry a foreigner, or, at the very least, date someone from each continent. And keep on traveling and crossing those borders.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

I once met an older man in the Sierra Madre of Mexico, an indigenous Raramuri/Tarahumara, who had walked out of his canyon, worked his way down to Peru, hopped on a ship to Japan as a stowaway, was arrested in the former Soviet Union as a spy, and eventually returned to his remote canyon as penniless as the day he left. He told his disbelieving friends and family: “I did not travel for riches, but rich experiences.”

Onward!