(Originally published in Holiday Magazine, July 1954)

Recently I drove from Garrison-on-Hudson to New York on a Sunday afternoon, one unit in a creeping parade of metal, miles and miles of shiny paint and chrome inching along bumper to bumper. There were no old rust heaps, no jalopies. Every so often we passed a car pulled off the road with motor trouble, its driver and passengers waiting patiently for a tow car or a mechanic.

Not one of the drivers seemed even to consider fixing the difficulty. I doubted that anyone knew what the trouble was.

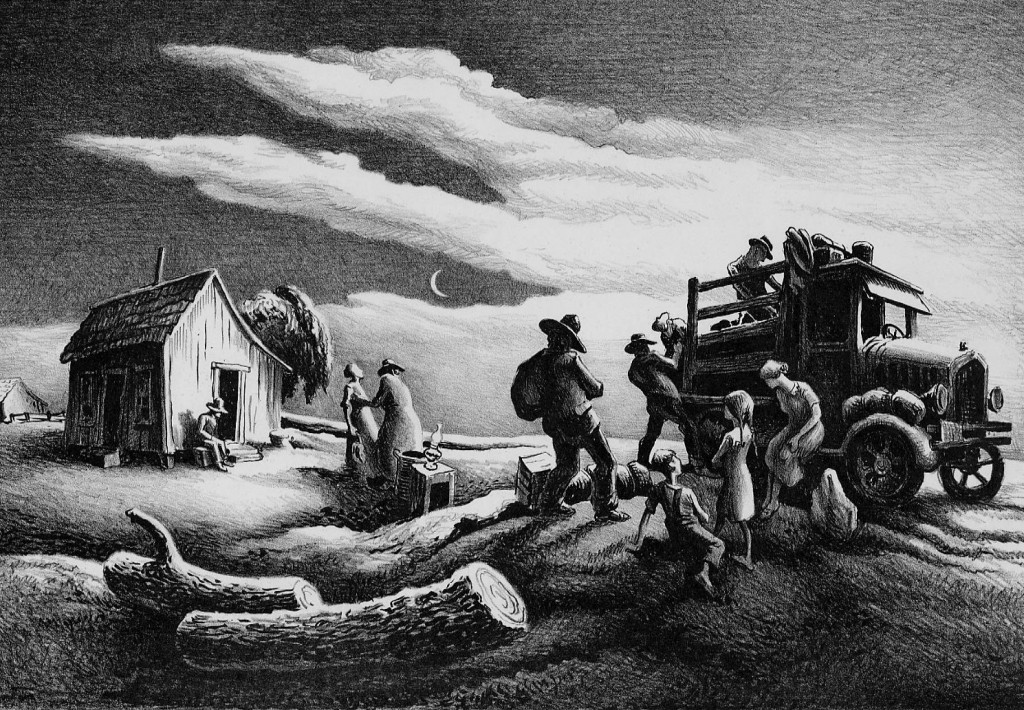

On this funereal tour I began to think of old times and old cars. Understand, I don’t want to go back to those old dogs. Any more than I want to go back to that old poverty. I love the fine efficient car I have. Rut at least I remembered. I remembered a time when you fixed your own car or you didn’t go any place. I remembered cars I had owned and cursed and hated and loved.

The first car I remember in the little town where I was born was, I think, a Reo with a chain drive and a steering bar. It was owned by a veterinary who got himself a bad name in Salinas for owning it. He seemed disloyal to horses. We didn’t like that car. We shouted insults at it as it splashed by on Stone Street. Then, gradually, more automobiles came into town, owned by the very rich. We didn’t have a car for many years. My parents never accepted the time-payment plan. To them it was a debt like any other debt, and to them debt was a sin. And a car cost a lot of money all in one piece.

Now it took a long time for a car to get in a condition where I could afford it, roughly about fifteen years. I had an uncle who ran a Ford agency but he didn’t give free samples to his relatives. He got rich selling Fords and himself drove a Stutz Bearcat—four cylinders, sixteen valves. Those were proud times when he roared up in front of our house with his cutout open, sounding like a rolling barrage. But this was dream stuff and not for us.

My first two cars were Model T’s, strange beings. They never got so beat up that you couldn’t somehow make them run. The first one was touring car. Chickens had roosted on its steering wheel and I never their marks off. The steering wheel was cracked so that if you put a weight on it it pinched your fingers when you let up. The back seat was for tools, wire and spare tires. I still confuse that car with my first love affair. The two were inextricably involved. I had it a long time. It never saw shelter or a mechanic. I remember how it used to shudder and sigh when I cranked it and how its crank would kick back viciously. It was a mean car. It loved no one, it ran in spurts and seemed to be as much influenced by magic as by mechanics.

My second Model T was a sedan. The back seat had a high ceiling and was designed to look like a small drawing room. It had lace curtains and cut-glass vases on the sides for flowers. It needed only a coal grate and a sampler to make it a perfect Victorian living room. And sometimes it served as a boudoir. There were gray silk roller shades you could pull down to make it cozy and private. But ladylike as this car was, it also had the indestructibility of ladies. Once in the mountains I stalled in a snow stoma a quarter of a mile from my cabin; I drained the water from the radiator and abandoned the car for the winter. From my window I could see it hub-deep in the snow. For some reason now forgotten, when friends visited me, we used to shoot at that car trying not to hit the glass. At a range of a quarter of a mile with a 30-30 this was pretty hard In the spring I dug it out. It was full of bullet holes but by some accident we had missed the gas tank. A kettle of hot water in the radiator, and that rolling parlor started right off. It ran all summer.

Model T’s created a habit pattern very difficult to break. I have told the following story to the Ford Company to prove their excellence. The cooling system of the Model T was based on the law that warm water rises and cool water sinks. It doesn’t do this very fast but then Model T’s didn’t run very fast. Now when a Model T sprang a radiator leak, the remedy was a handful of corn meal in the radiator. The hot water cooked the meal to mush and it plugged the leak. A little bag of meal was standard equipment in the tool kit.

In time, as was inevitable, I graduated to grander vehicles. I bought an open Chevrolet which looked like a black bathtub on wheels, a noble car full of innovations. I was living in Los Angeles at the time and my mother was coming to visit me. I was to meet her at the station, roughly thirty-five miles from where I lived. I washed the car and noticed that the radiator was leaking. Instinctively I went to the kitchen and found we had no corn meal, but there was oatmeal which is even better because it is more gooey. I put a cup of it in the radiator and started for the station.

Now the Chevrolet had a water pump to circulate the water faster. I had forgotten this. The trip to the station must have cooked the oatmeal thoroughly.

My mother arrived beautifully dressed. I remember she wore a hat with many flowers. She sat proudly beside me in the front seat and we started for home. Suddenly there was an explosion—a wall of oatmeal rose into the air, cleared the windshield, splashed on my mother’s hat and ran down her face. And it didn’t stop there. We went through Los Angeles traffic exploding oatmeal in short bursts. I didn’t dare stop for fear my mother would kill me in the street. We arrived home practically in flames because the water system was clogged and the limping car gave off clouds of smoke that smelled like burned oatmeal, and was. It took a long time to scrape my mother. She had never really believed in automobiles and this didn’t help.

In the days of my nonsensical youth there were all kinds of standard practices which were normal then but now seem just plain nuts. A friend of mine had a Model T coupé, as tall and chaste as a one-holer. It rested in a lot behind his house and after a while he became convinced that someone was stealing his gasoline. The tank was under the front seat and could ordinarily be protected by locking the doors. But this car had no locks. First he left notes on the seat begging people not to steal his gasoline and when this didn’t work he rigged an elaborate trap. He was very angry, you see. He designed his snare so that if anyone opened the car door, the horn would blow and a shotgun would fire.

Now, how it happened we don’t know. Perhaps a drop of water, perhaps a slight earthquake. Anyway, in the middle of the night the horn went off. My friend leaped from bed, put on a bathrobe and a hat, I don’t know why, raced out the back door shouting “Got you!”—yanked open the car door and the shotgun blew his hat to bits. It was his best hat too.

Well, about this time the depression came along and only increased the complications. Gasoline was hard to come by. One of my friends, wishing to impress his date, would drive into a filling station, extend two fingers out the window, out of the girl’s sight, and say, “Fill her up,” Then, with two gallons in the tank he would drive grandly away. This same friend worked out a way of never buying a license, which he couldn’t afford anyway. He traded his car every time a license fee was due, but he only traded it for a car with a new license. His automobiles were a little worse each time but at least they were licensed.

With the depression came an era of automotive nonsense. It was no longer possible to buy a small car cheaply. Everyone wanted the Fords and Chevrolets. On the other hand, Cadillacs and Lincolns could be had for a song. There were two reasons for this. First, the big cars cost too much to run and, second, the relief committees took a sour view of anyone with a big expensive-looking car. Here is a story somewhat in point.

A friend of mine found himself in a condition of embarrassment which was pretty general and, to him, almost permanent. An old school friend, rich and retired, was going to Europe and suggested that George live in his great house in Pebble Beach in California. He could be a kind of caretaker. It would give him shelter and he could look after the house. Now the house was completely equipped, even to a Rolls-Royce in the garage. There was everything there but food. George moved in and in a firs flush of joy drove the Rolls to Monterey for an evening, exhausting the tank. During the next week he ate the dry cereals left in the kitchen and set traps for rabbits in the garden. At the end of ten days he was in a starving condition. He took to staying in bed in luxury to conserve his energy. One morning, when the pangs of hunger were eating at him, the doorbell rang. George arose weakly, stumbled across the huge drawing room, across the great hall carpeted in white, and opened the baronial door. An efficient-looking woman stood on the porch. “I’m from the Red Cross,” she said, holding out a pledge card.

George gave a cry of pleasure. “Thank God you’ve come,” he said. It was all crazy like that. It was so long since George had eaten they had to give him weak soup for quite a while.

At this time, I had an old, four-cylinder Dodge. It was a very desirable car—twelve-volt battery, continental gearshift, high-compression engine, supposed to run forever. It didn’t matter how much oil it pumped. It ran. But gradually I detected symptoms of demise in it. We had developed an instinct for this. The trick was to trade your car in just before it exploded. I wanted something small but that I couldn’t have. For my Dodge and ten dollars I got a Marmon, a great, low, racy car with aluminum body and aluminum crankcase—a beautiful thing with a deep purring roar and a top speed of nearly a hundred miles an hour. In those days we didn’t look at the car first. We inspected the rubber. No one could afford new tires. The tires on the Marmon were smooth but no fabric showed, so I bought it. And it was a beautiful car—the best I had ever owned. The only trouble was that it got about eight miles to the gallon of gasoline. We took to walking a good deal, saving gasoline for emergencies.

One day there was a disturbing click in the rear end and then a crash. Now, anyone in those days knew what had happened. A tooth had broken in the ring gear of the rear end. This makes a heartbreaking noise. A new ring gear and pinions installed would come to ninety-five dollars or, roughly, three times what I had paid for the whole car.

It was obviously a home job, and it went this way. With a hand jack, I raised the rear end onto concrete blocks. Then I placed the jack on blocks and raised again until finally the Marmon stuck its rear end up in the air like an anopheles mosquito. Now, it started to rain. I stretched a piece of oilcloth to make a tent. I drained the rear end, removed the covers. Heavy, black grease ran up my sleeves and into my hair. I had no special tools, only a wrench, pliers and a screw driver. Special tools were made by hammering out nails on a brick. The ring gear had sheared three teeth. The pinions seemed all right but since they must be fitted, I had to discard them. Then I walked to a wrecking yard three miles away. They had no Mormons. It took a week to find a Marmon of my vintage. There were two days of bargaining. I finally got the price down to six dollars. I had to remove the ring gear and pinions myself, but the yard generously loaned tools. This took two days. Then, with my treasures back at my house I spent several days more lying on my back fitting the new parts. The ground was muddy and a slow drip of grease on my face and arms picked up the mud and held it. I don’t ever remember being dirtier or more uncomfortable. There was endless filing and fitting. Kids from as far as six blocks away gathered to give satiric advice. One of them stole my pliers, but pliers were in the public domain. I had probably stolen them in the first place. I stole some more from a neighbor. It wasn’t considered theft. Finally, all was in place. Now, I had to make new gaskets out of cardboard and tighten everything all around. I put in new grease, let the rear end gently down. There was no use in trying to get myself clean—that would take weeks of scrubbing with steel wool.

Now, word got around that the job was done. There was a large and friendly delegation to see the trial run—neighbors, kids, dogs, skeptics, well-wishers, critics. A parrot next door kept saying “Nuts!” in a loud squawking voice.

I started the engine. It sounded wonderful; it always sounded wonderful. I put the car in gear and crept out to the street, shifted gears and got half a block before the rear end disintegrated with a crash like the unloading of a gravel car. Even the housing of the rear end was shattered. I don’t know what I did wrong but what I did was final. I sold the Marmon as it stood for twelve dollars. The junkman from whom I had bought the ring gear hauled it away—aluminum body, aluminum crankcase, great engine, silver-gray paint job, top speed a hundred miles an hour, and pretty good rubber too. Oh, well—that’s the way it was.

In those days of the depression one of the centers of social life was the used-car dealer’s lot. I got to know one of these men of genius and he taught me quite a bit about this business which had become a fine art. I learned how to detect sawdust in the crankcase. If a car was really beat up, a few handfuls of sawdust made it very quiet for about five miles. All the wiles and techniques of horse-trading learned over a thousand years found their way into the used-car business. There were ways of making tires look strong and new, ways of gentling a motor so that it purred like a kitten, polishes to blind the buyer’s eyes, seat covers that concealed the fact that the springs were coming through the upholstery. To watch and listen to a good used-car man was a delight, for the razzle-dazzle was triumphant. It was a dog-eat-dog contest and the customer who didn’t beware was simply unfortunate. For no guarantee went beyond the curb.

My friend in the used-bar business offered a free radio in every car sold for one week. Now, a customer came in who hated radios. My friend was pained at this. The customer said, “All right, how much will that car be without a radio?”

My friend wrote some figures on a pad. “Well,” he said, “I can let you have it for ten dollars extra—but I don’t want to make a practice of it.”

And the customer cheerfully paid.

It’s all different now. Everything is chrome and shiny paint. A car used to be as close and known and troublesome and dear as a wife. Now we drive about in strangers. It’s more comfortable, sure, but something has been lost. I hope I never get it back. ◊

Holiday was a pioneering American travel magazine published from 1946 to 1977. Holiday‘s circulation grew to more than one million subscribers at its height, and employed writers such as Truman Capote, Joan Didion, Lawrence Durell, James Michener and E. B. White.