In re-reading Pilgrims in a Sliding World (my never-published first attempt at a travel book), I’m often struck by how young the narrator seems. This makes perfect sense, of course, since the book evokes a 24-year-old version of me trying to narrate the exploits of a 23-year-old version of me.

Admittedly, I didn’t feel all that young at the time, but – 30 years later – the person I portrayed on the page comes off as so youthful and naïve as to be downright neurotic.

This tension is encapsulated in a North Carolina section from Chapter Fourteen (“Malfunction”), not long after I’d parted ways with an old friend named Casey, who’d told me that my earnest belief in her a few years earlier had helped her deal with mental illness. Apparently, this revelation unsettled me:

My brain hung heavy as we drove, semi-formed thoughts smacking into my mind like bugs. In reminding me of something I’d done at age nineteen—some good thing I’d done at age nineteen—Casey had opened up a small hole in my psyche, and what I saw through that hole bothered me. What I saw was the shadow of a slightly-different me; an incomplete post-mortem of belief; faint echoes telling me that—perhaps—I have become less of a person than I was at age nineteen.

Three things about this paragraph stand out to me. First, it’s overwritten, and a bit clunky with its metaphors. Second, it alludes to a nebulous conflict without attempting to clarify what exactly it was. (What psychic shift made me feel like I was becoming “less of a person than I was at age nineteen?”; decades later I have no idea, and I suspect the young narrator wasn’t sure either.)

The final thing that stands out is young Rolf’s perspective on himself as he sees himself getting older. It’s easy, I think, to forget the ways we make sense of ourselves by comparing ourselves to who we think we were before.

I’ll admit that’s exactly what I’ve been doing here, of course. That in mind, I’ll try not to be too hard on the young version of me that wrote Pilgrims in a Sliding World, even as I identify where he was lacking as a memoiristic storyteller.

Writing that reads like “writing” should probably be rewritten

When I teach my travel writing classes each summer in Paris, one of my craft lectures draws on novelist Elmore Leonard’s “10 Rules of Writing,” which ultimately asserts: “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

Writing that “sounds like writing” often lurks in the very passages a given writer is most proud of having written – and it’s obvious that young Rolf was smitten with figurative language that ultimately did little more than draw attention to itself. Take for example this paragraph from Chapter Seven (“Walking My Corpse Through Texas”):

Hangovers are like shadows of bad judgement—tedious epiphanies that remind you, in no uncertain terms, that you are an idiot. To say that I woke up hung-over in San Angelo would be to say that Egypt had a bug problem during the biblical Plague of Locusts. I felt like I was living through death. I slid out of the van to walk off my nausea—muscles aching, nasal passages jammed with phlegm, skin flushed with feverish heat, brain rattling inside my head like a sodden lump of clay. Every time I coughed, I saw psychedelic fireworks. I took a couple steps, then staggered back to the safety of the Vanagon. I felt like my entire body had been guillotined off below the feet and discarded.

This over-wrought attempt to describe a hangover was clearly hyperbolic – and while I’m certain it was an attempt at humor, its syntax drew attention to itself without being all that funny.

Elsewhere in the book, my prose stretched its metaphors and symbolism far beyond the breaking point. In describing driving through an isolated stretch of Big Sur coast in Chapter Three (“Burrowing Through the Topsoil”), for instance, I observed how the massive yellow barrenness of the land contrasted starkly with the enormous, deep-blue expanse of water to the west. “Nothing else holds my attention in this dreamland between San Francisco and Los Angeles,” I declared, “just yellow, blue, and a small highway carved into the contours where the colors crash against one another.”

This passage might have worked as a poetic evocation of what driving down California’s wilderness coast felt like, had I not immediately plunged deeper into the realm of hyperbole, symbolism, and metaphor:

Sometimes I feel as if I need help with my strokes here in the yellow part of the world. As I travel, I am nagged by the idea that I might be missing something as I splash from place to place—that my choices are a desultory collection of uninformed guesses. I am tempted to trade my freedom of choice for the deep-blue finality of the ocean—so that I could simultaneously touch the colors of every shore instead of burrowing through my own limited perceptions like a mole in the topsoil. Unfortunately, such omniscience is not an option. Daunting as it may be, free-will is my most potent weapon in this life. Often, this makes me feel like a monkey at a typewriter—whimsically punching keys in the hope that I will end up with something worthwhile.

Over-writing aside, this passage reveals how – three chapters into the book – I was still trying to find new ways to express the book’s inciting conflict (and professed reason for making the journey): I.e., my own ambivalence about my future in the face of the American Dream.

Unlike some of the other sections of the book, which recount experiences I only faintly remember outside of the book itself (and/or the journal entries that informed it), I clearly remember the emotions I felt while driving the Big Sur coast, as well as the task of trying to write about it. I recall being particularly proud of this section:

To the west, the ocean is ablaze with a flat and smokeless flame, dancing across the deep-blue. The futures we will never see are burning as we burrow through this multi-colored world. Motion is a simultaneous act of creation and destruction: the pure vision of this life rises from the ashes of what we will never experience. Beneath the late-day glow, I suspect that even the ocean is grieving. The ocean is grieving at its own deep-blue omniscience: it is grieving because all it will ever do is wash away at the shores it touches. It is grieving because all it will ever be is the ocean: it is grieving at the loss of possibility.

In the fading light, the land and the ocean open up and drop into grey: they become nothing. From this nothingness comes a fearsome sense of freedom, an unexpected intimacy with America, an intuitive sense of beginning. For a moment—somewhere in this gaping synapse between California’s megalopolitan concrete kingdoms—future and past become void in the terror and beauty of motion: Jeff drives, and I breathe in.

The existential tenor of this passage owed a lot to a quote from Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset (which, fittingly enough, I’d recently discovered in a Details magazine essay by musician Gordon Gano): “The youth, because he is not yet anything determinate and irrevocable, is everything potentially. …Feeling that he is everything potentially, he supposes that he is everything actually.”

In a sense, I concocted that “ocean is ablaze” passage to make sense of the Big Sur experience for myself (and, decades later, that feels like a worthy effort, even if it didn’t quite weave its way into a publishable narrative).

Writing that’s trying to sound smart has a way of working against itself

An early reader of the various Pilgrims in a Sliding World chapters was my sister Kristin, and one of her most witheringly helpful suggestions was that some of my insights came off sounding like “Deep Thoughts” by Jack Handey, from Saturday Night Live.

Having my insights compared to the absurdist faux-wisdom of late-night sketch comedy was humbling, to be sure, but it helped me become aware of the pitfalls of trying too hard to sound smart – of straining for profundity, rather than quietly evoking something profound.

Often my writing flirted with depicting things in a true way, before eventually veering into half-basked philosophizing. Take for example this passage from Chapter Seventeen (“Alienation by the Numbers”), about the mix of exhilaration and loneliness I felt while walking around Manhattan alone at night amid my first-ever visit to New York:

As I took the nearly-empty #6 subway to the East Village, I felt a vague sense of adolescent exhilaration—as if I were a fourteen-year-old sneaking out of my house to meet a girl or vandalize my junior high school. I felt as if something new was about to happen. …I stopped on the corner of Fifth Avenue and looked at the tidy illuminations of the buildings. All the man-made order seemed just efficient enough to eliminate the need for God and just chaotic enough to preclude the significance of everybody else. I thought of pigeons roosting in skyscrapers and dreaming of forests, of heaven parceled by landlords. I felt dull and delusive, like my heart was thumping out a secret code that translated into nonsense. One hour alone in the streets of New York and I was already lonesome.

Not long before that episode, in Chapter Thirteen (“Channel Changers and Missing Persons”), I did a nice job of describing the simple camaraderie and connection that came with building a campfire in the North Carolina forest, only to ruin it with this attempt at existential sagaciousness:

Jacinthe has instructed us to turn away from the flames and watch our shadows dance. As I watch the light flicker out toward the trees, it occurs to me that shadows are not merely a fleeting, secondary phenomenon. Shadows are darkness, and darkness is a constant. When we recall our lives, we recall the events lived in the unshadow—in the light, in the sun. And what is this campfire but a small portion of the sun that has been trapped in these branches—now escaping to warm us and remind us of the darkness that dances behind us. It occurs to me how profound a blessing the sun is. I think of the wild odds that conspired to make this world as it is, and—in an instant of childish fear—I wonder what would happen if those odds suddenly gave out on us. What would happen if the sun decided on this night to go away and leave us cold? This is a foolish supposition, but knowing that does not stop me from turning to face the fire again.

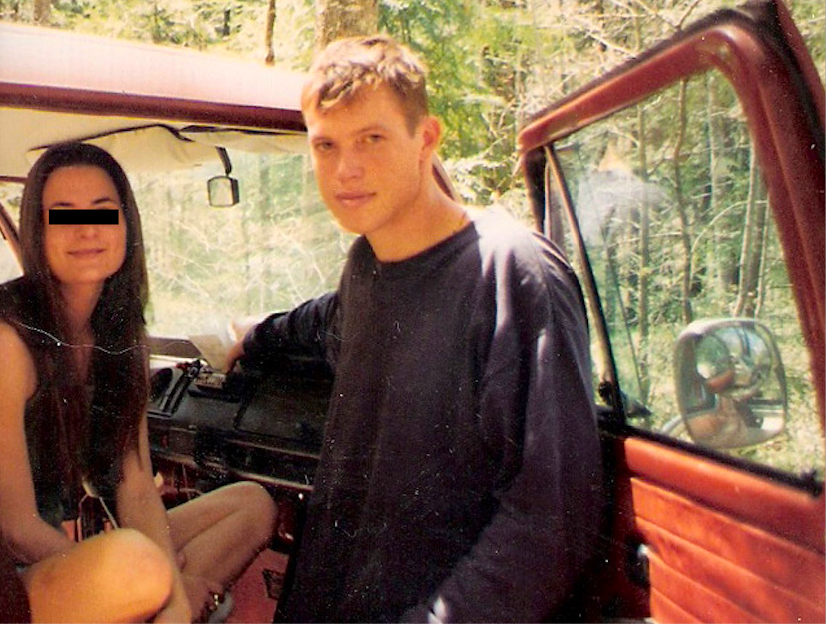

It is perhaps telling that I’d tried to shoehorn an attempt at profundity into a campfire sequence that involved cute a pair of cute young women (Jacinthe, and her friend Ashley) that my friend Jeff and I had met in Georgia a few days earlier.

At the time, I’d enjoyed a flirtation with Ashley, even as I was longing for a young woman named Skye whom I’d met one month before in Florida. You’d never guess at this romantic tension Chapter Thirteen of Pilgrims in a Sliding World, however, because I was too busy trying to draw cosmic significance out of the campfire.

Tip #7: Balance narrative analysis with narrative vulnerability

I find it curious that popular culture invariably portrays young men as mindless, sex-obsessed horn-dogs, since I was awkwardly chaste and honorable in the presence of attractive young women when I was 23 (and I suspect many young men are).

This is not to say that I was a good romantic prospect at that age, since my own self-consciousness invariably proved frustrating to the women I was trying to woo.

For a hint at this dynamic, consider the analytically honest (if circuitous) way I foreshadowed my dalliance with Skye in Chapter Twelve (“Deathbed Smile-Quest”):

In pursuing romance, you get to know yourself while getting to know someone else. All of the hypotheses you make about who you are get put to the test when you are presenting yourself to another person. It can be like getting your life audited. I have spent the last day here in Ocala trying to make sense of my audit. Such audits rarely go well for me. Sometimes I feel like I should write apologies to all my ex-girlfriends, although I’m not exactly sure what I should be sorry for. Perhaps my flaw is that I have fooled myself into thinking that I have good intentions without actually having good intentions. This is as bad as it can get, because I spend all of my time trying to prove something that does not exist. To me, women are like members of a magical culture that I can respect and fear—but never properly comprehend. If I said this to the girl I have been thinking about all day, she would tell me I was just trying to invent a flowery way to say I was scared of commitment. She probably would be right. Her name, by the way, is Skye.

Part of the challenge in depicting my love life at that age was that I overthought everything. Writing about Skye was difficult for me because I still longed for her, even as I tried to make narrative sense of her a full year later. Toward the end of Chapter Twelve, I mused that my short Florida romance with her “was perfect, because it was all spark and no realism; we didn’t worry about the future because we both knew I was just passing through.”

The thing is, Skye wound up coming to see me later that year in Denver, and then again at Yellowstone – two incidents that never made it into Pilgrims in a Sliding World because I abandoned the manuscript before I made it that far into the journey.

Hence, in trying to write about Skye, I was trying to tell a story without really knowing the ending. The moments that do evoke something real about my interactions with Skye aren’t the ones drenched in analysis, but in straightforward vulnerability. Take this sequence that comes just after the vaguely articulated angst I described above, in Chapter Fourteen (“Malfunction”):

My call to Florida woke Skye. I bantered cheerily and stupidly—the whole time thinking I should tell her that what had happened between us a few weeks prior was really meaningful to me. Thing is, I didn’t know if that was even true. I didn’t even care if it was true. What I really wanted was for her to say it to me; for her to give me a sign that I had passed some test that I’d never taken. Skye, of course, was friendly and realistic. If she couldn’t solve my malfunctions, she was at least doing a better job of dealing with my lifestyle than I was. We talked pleasantly about nothing, then hung up.

In depicting myself in a vulnerable, less-than-idealized way, I was able to evoke something honest about the real emotional texture of my journey – something that no amount of portentous analysis could replicate.

Had I been more willing to embrace this narrative vulnerability (and more willing to make myself look unsympathetic), Pilgrims in a Sliding World would have been a much better book.

Curiously, some of the philosophical reflections that appeared Pilgrims in a Sliding World foreshadowed the travel ethos that underpinned my eventual first book, Vagabonding. I’ll look at those parallels in the next entry.