Ten years ago, when I first visited Egypt, I had a hang-up about visiting the legendary Pyramids at Giza. At the heart of this hang-up was the dull fear of disappointment — a creeping worry that the most iconic monument in the world would be so overrun by tourists and kitsch vendors that I wouldn’t truly appreciate it. I eventually found my courage and made my pilgrimage to Giza (though my one-week spate of creative Pyramid-procrastination in the streets of Cairo was so revealing that it took up an entire chapter of my book Marco Polo Didn’t Go There).

My only regret in that original visit to Giza is that I was so self-conscious about the kitsch-factor at the Pyramids that I neglected to properly appreciate it. This site has, after all, been a locus of tourist fascination for at least 3200 years (the oldest recorded tourist graffiti at the Pyramids, dated to 1244 BC, reads: “Hadnakhte, scribe of the treasury, came to make an excursion and amuse himself on the west of the Memphis, together with his brother, Panakhti”). By the time Herodotus visited the Pyramids in 450 BC, the touts, guides, and vendors of Giza had been making a living catering to the whims and credulities of tourists for nearly twenty generations (which could account for some of the dubious Egypt data in the Greek writer’s Histories).

One of the more colorful accounts of Pyramid tourism in the 19th century came from Mark Twain, who was simultaneously impressed by the sights at Giza, and irritated by the hordes of would-be guides and souvenir salesmen. “We suffered torture no pen can describe from the hungry appeals for bucksheesh [tips] that gleamed from Arab eyes and poured incessantly from Arab lips,” Twain wrote in The Innocents Abroad. “Why try to call up the traditions of vanished Egyptian grandeur; why try to fancy Egypt following dead Rameses to his tomb in the Pyramid, or the long multitude of Israel departing over the desert yonder? Why try to think at all? The thing was impossible.” (Twain’s ultimate solution was to pay one tout to fight off all the other touts while he made his way around the site.)

Since the tourist scene at Giza has a history almost as lengthy and storied as the Pyramids themselves, I wanted to focus my latest visit on the very touts and vendors I’d tried to ignore ten years before. One of the clichés of travel writing is the tendency to ignore all the present-day annoyances (including other the tourists) that surround sites of ancient grandeur. This in mind, I hoped to engineer a visit that focused less on the Pyramids than the chaotic human interactions that surround them.

Given the fact that (with the help of my cameraman Justin) I was shooting this experience for video, my Giza visit quickly devolved into good-natured absurdity. Whereas my travel-reflexes are typically honed to ignore the trinket-vendors and freelance guides that surround a given tourist site, this time I was actually seeking to interact with them. Since it’s impossible to have a normal conversation with a tout (who by definition wants only to talk you into using his services), this led to a series of spirited-yet-pointless interactions outside the Sphinx-side admission gate.

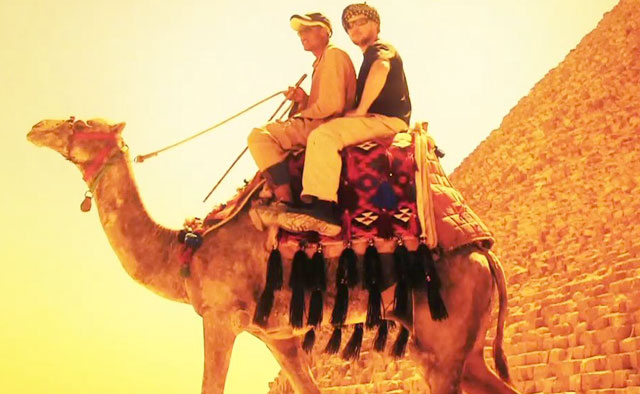

Eventually, over the course of one morning, I racked up: a) one mediocre desert horse excursion (which was spearheaded by a pot-bellied Egyptian named Nasser, who seemed disproportionately concerned that I might need help buying souvenirs after the ride); b) nearly a dozen visits to papyrus shops and handicraft stores (I have no room for souvenirs, but Justin got some goodies for his wife); c) one denial of admission at the Sphinx gate (due to the presence of the video camera); d) one successful admission at the main gate (once we’d hidden the microphone to make the camera look less official); and e) one camel ride from the most spectacularly persuasive and devious tout I’ve met in all my years of travel (he basically invited me to sit on the camel for one photo, then didn’t let me down for the next half hour).

This all made for a gloriously unoriginal experience at Giza — which, on this day at least, was exactly what I was looking for.