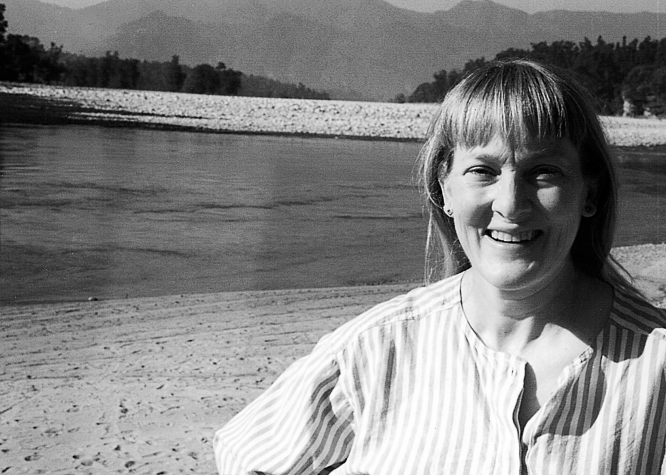

Catherine Watson, a pioneer in narrative travel writing for newspapers, was the first travel editor at the Minneapolis Star Tribune and its chief travel columnist from 1978 to 2004. Her books, Roads Less Traveled: Dispatches From the Ends of the Earth (Syren Book Company, 2005) and Home on the Road: Further Dispatches from the Ends of the Earth (Syren, 2007), both won awards from the Society of American Travel Writers and were finalists in the Minnesota Book Awards. Watson’s work has been anthologized in The Best American Travel Writing 2008 (Houghton Mifflin, 2008); Tuesday in Tanzania (New Rivers Press, 1997), and eight collections by Travelers’ Tales: A Woman’s World (1996), A Woman’s Passion for Travel (2000), Turkey (2002), A Woman’s Europe (2004), A Woman’s World Again (2007), Encounters with the Middle East (2007), Travelers’ Tales Best Travel Writing 2008 and Best Women’s Travel Writing 2009. Her honors include the Lowell Thomas Travel Journalist of the Year and the Society of American Travel Writers Photographer of the Year.

How did you get started traveling?

I never imagined not traveling — it was just a given. I blame World War II, because my interest in foreign places grew directly from my father’s experiences in England before the D-Day invasion and in France afterward. He told me war stories when I was little, so I knew what the Eiffel Tower looked like before I’d even heard of the Empire State Building or the Washington Monument.

He came out of the Air Force afraid of flying, so every family trip had to be by car. By the time I was a teenager, we were taking a five- or six-week road trip every summer. Our family wasn’t one of those happy, totally in-sync Brady Bunches, but my parents did a remarkably good job of teaching my four siblings and me how to travel. We went all over the continent, from the Arctic Circle to the southern border of Yucatan, mostly via a silver travel trailer (not an Airstream but an Avion, because my father liked off-brands), later with a chassis-mounted truck camper.

I don’t know how my mother felt about it, but my father hated planning, and he liked getting lost. I picked up both those attitudes. He also refused to stop at any attraction kids like. There were no Treasure Caves, Mystery Spots or Reptile Farms for us, though he did break down once and take us to Wall Drug. Otherwise, it was Yellowstone, Mesa Verde, Grand Canyon, Bryce, Zion, Yosemite, the Great Smokies, and every historic town, village, national monument and battlefield in between.

Every trip was a crash course in geography, history, culture, anthropology, religion, even local politics. In the car, kids were assigned to take turns reading aloud to the rest of the family about the places we were coming to. Wherever we stopped, we had to go out in teams — big kids watching little kids — and find things out. In Mexico, for example, my parents routinely sent us off into crowded public markets to shop for food, and we learned first-hand how kind people could be, even when they’d never met us before and couldn’t understand what we were saying.

Later on, my parents encouraged me to be an exchange student — to Germany on American Field Service (now AFS International) and, in college, on the Minnesota SPAN program to Lebanon. But it was those family trips that set my path. They added up to the best training a travel writer could have.

How did you get started writing?

That began in childhood too. I started keeping a journal when I was nine, the same year that I got a Kodak Brownie Hawkeye — a small box camera — for Christmas. But it never occurred to me to be a writer. I thought writing was just something everyone did.

What I really wanted to be, from age 7 on, was an archaeologist. That lasted until I spent a college summer on a dig in Lebanon. We were trying to establish a chronology for pottery in the Bekaa Valley, and part of my job was reassembling a 4-foot-tall amphora; I got maybe 10 inches of the shoulder done, and it took weeks. I’d pictured archaeology as something more swashbuckling. (What I’d pictured, of course, was Indiana Jones, except he hadn’t been invented yet.)

I went home and switched majors — again and again and again, six majors in all — which left me unfit for any single profession but really well prepared for games of Trivial Pursuit. And journalism, where all those bits of knowledge came in handy.

What do you consider your first “break” as a writer?

The Vietnam War (I’m noticing a military theme here). My newspaper later referred to its hiring policies then as “early affirmative action,” but it was no such thing. It was just economics.

I’d gotten a college internship at the old Minneapolis Tribune (later the Star Tribune), which led to a job as a general assignment reporter. It was the middle of the Vietnam War, and women were still fairly rare in newsrooms. But management was tired of having to hold jobs open for male staffers who got drafted. So they started hiring women — in large numbers (among them, the late, great Molly Ivins). Nearly all of us stayed in the business, even after the men came back.

I went on to a variety of jobs, including editing our Sunday magazine, but I spent every spare dollar on travel. When the Tribune started its travel section in 1978, I was named its editor. I knew then that I was a lifer, because the paper was going to pay me to do what I already loved. I stayed in that job for the next 26 years, during which time the paper sent me to more than 100 countries, and I discovered that I had a voice and that readers responded best when I used it to tell travel stories first-person.

That’s really the only way to do it effectively, I think, because you can’t accurately generalize about, say, India — but you can tell authentic stories about what happened to you in India. One of my editors called this approach “being the guide, not the hero,” which is exactly what I’d been trying to do.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

Fear. Not of anything happening to me, but of failing. Fear that I won’t get enough information, or take good enough pictures, or write a good enough story.

What is your biggest challenge in the research and writing process?

Making myself start writing. I know how hard it’s going to be. The more important the assignment, the more I want it perfect, and the more I put off — what? — commitment, I guess. Once I jump in and start writing, even if it’s just copying over my notes, I’m underway, and then everything’s fine.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint?

Marketing! I hate having to cajole editors into using my stuff. I never had to do that when I was at my paper — I could simply get an idea, take a trip and write the story. So now I feel like a beggar, and — like a lot of freelancers — I put off the marketing, concentrate on the writing and, surprise, surprise, have to keep on begging.

Have you ever done other work to make ends meet?

Yes. I teach writing workshops — week-long intensives in travel writing and memoir. I began doing that while I was still at the Star Tribune and stepped it up after I left. This summer, I led my 13th workshop for the University of Minnesota’s Split Rock Arts Program.

I’m also a long-distance coach in travel writing and memoir for the U of M’s On-line Mentoring for Writers Program. Students apply and are matched with one of a dozen nationally known writers; the mentees submit work online, the mentors give feedback online, and the university monitors the whole online arrangement.

What travel authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

The Royal Road to Romance, the 1922 classic by Richard Halliburton. Mark Twain’s travel books. Anything by Pico Iyer. Paul Theroux”s The Great Railway Bazaar. Tony Horwitz‘s Confederates in the Attic. The Caliph’s House’ by Tahir Shah. And at least a zillion others.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

Do it for love. You won’t get rich. But if you love it, you won’t care.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

The world. The whole, damned, beautiful, complicated, aggravating, incredible world. And the freedom that comes with it. I feel most alive when I am out there, on the road, meeting people, asking questions — not just for myself, but on behalf of readers. I’m a better traveler when I keep my audience in mind: They help me be braver, more curious, my best self — because I’m traveling for someone besides me.