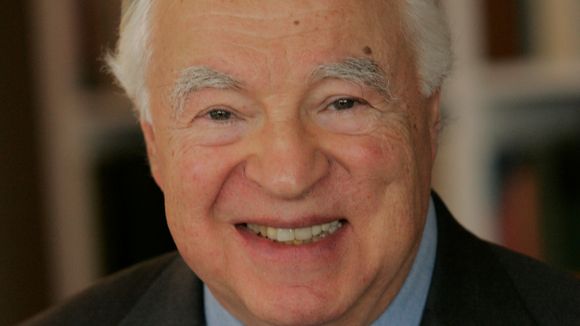

Arthur Frommer, one of America’s foremost travel authorities, is the founder of the Frommer’s guidebook series. He is the author of scores of travel books, including the pioneering budget guide Europe on $5 a Day. In addition to guidebooks, his writings include hundreds of travel articles and columns appearing in magazines ranging from Readers Digest to Consumers’ Digest. He also presents a weekly radio program on travel, appears as a travel commentator for numerous TV programs, and writes a weekly travel column that appears in major newspapers ranging from the New York Daily News to the Chicago Tribune to the Los Angeles Times. He lives in New York City.

How did you get started traveling?

By accident, and at the expense of Uncle Sam. I was drafted into the army when I graduated from the Yale University Law School. The Korea War was going on at that time, and I was trained to be an infantryman in Korea when someone in the Pentagon must have discovered some of my linguistic abilities. I was assigned instead to Berlin. I wanted to pinch myself for my good luck. I had never dreamed that I would ever be able to see Europe, as I came from a family of very modest income.

And there I was smack in the heart of Europe with a strong US dollar and I utilized every opportunity I could find, every weekend and three-day pass, to simply travel throughout Europe regardless of how little money I had. I was living on a PFC’s salary. And in the course of doing that it occurred to me that I should write a book about the experience.

I discovered that the fact that I had very little money had transformed the quality of my vacation and travels and made them far more rewarding and far more pleasant. I discovered that the less you spend the more you enjoy — the more authentic is the experience you have.

How did you get started writing?

I’d always written. I’d gone to University of Missouri — initially I’d wanted to be a journalist. I spent my first year there, but my mother got ill and I had to return to New York. I spent my next three undergraduate years at New York University, where I was a political science major, and I won a scholarship to Yale University Law School. I had never really looked upon myself as a writer, but of course I did an enormous amount of writing in college and in law school. I was also the editor of the Yale Law Journal and did a great deal of writing there. But writing came easily to me and I enjoyed doing it.

What do you consider your first “break” as a travel writer?

In the last three weeks of my army service I wrote a little book called The GI’s Guide to Traveling in Europe. It included all the special lessons for GI’s who were servicemen stationed in Europe: How to get free Air Force flights, where to find them, military lodgings in Paris and London where you could live for fifty cents a night — that kind of thing.

I published that book myself. It was so successful that when I came home to begin the practice of law, the idea was rolling around in the back of my mind that I should do the same thing for civilians. In 1957 I published a little book called Europe on $5 a Day, of which I printed 5000 copies. These sold out the first afternoon they appeared in bookstores, and that caused me again to realize that I’d stumbled upon the avid desire of people for this type of information. That led to the creation of a publishing company that now publishes over 360 titles a year. The Frommer guides are now the largest selling travel guides in North America, and they account for close to one out of every four sold travel guides sold in the United States.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

My biggest challenge is to keep my own eyes and consciousness fresh. I’ve realized that there was such a thing as too much travel, which causes you to be jaded.

There was a moment when my plane landed at the airport of Amsterdam one day and I didn’t even take my eyes away from the book that I was reading because I was as familiar with Amsterdam as I was with my own home city. And I suddenly realized that that’s not the mood with which travelers approach a new destination — travel is exciting and novel and somewhat bewildering. And it’s very important, even for an experienced travel writer: not to become jaded and not to relax, but to keep in mind the tingling excitement that most tourists feel when they encounter a foreign destination for the first time.

That has led to a style of writing in which nothing is left out — in which you don’t assume anything, in which you take the reader by the hand and lead him through the steps he will need to absorb in order to enjoy a particular destination.

What is your biggest challenge in the writing process?

The challenges are to be of real service to the traveler. Too much travel writing is simply an exercise on the part of the writer that is of no relevance to the person reading the information.

If there is anything that has distinguished our travel guides and my blog from all the other travel guides and blogs, it’s that we are constantly striving to be of real service and assistance to the public. We are constantly striving to describe those destinations — those travel experiences — which a large number of Americans will find of relevance to their lives.

What have been your recent challenges from a business standpoint?

When the Internet came about, and it was suggested that we place the content of our travel guides onto the Internet, I was quite apprehensive. I kept thinking that we were committing suicide, that we were eliminating the need to buy a travel guide. And yet that hasn’t happened. With all the material that appears on the Internet — with the ease with which people can obtain the very same text that appears in a printed travel guide — the sale of printed travel guides has not been affected in the slightest. To my amazement, the mass of information that is now on the Internet has had no impact upon the publication of printed travel guides.

Increasingly, in recent years, our guidebooks are written by residents of the islands and the cities and the nations that are written up in those guidebooks. We are making less and less use of generalists who are able to parachute in to a particular destination and write about them. We are trying to find an expert to write about his or her own city, his or her own nation. We find that that leads to excellent material.

I no longer have any connection with Budget Travel magazine, and am profoundly disappointed by the turn it has taken. I no longer believe it provides service to the budget-minded tourist. I’m very unhappy about the fact that my name continues to appear on it.

Do you do any other kinds of work to make ends meet?

My income comes from various activities involving travel. I publish travel guides, I do a twice a week column that is syndicated to many major newspapers by King Features, I do a Sunday afternoon radio program on WOR, and I write a great many articles as a freelancer for magazines.

What travel authors have influenced you?

I don’t think I was influenced by any other authors of travel guides per se, but I loved reading general travel memoirs about trips that people have taken. I remember that Richard Halliburton had an immense impact on me earlier in my life when I read him as a young boy.

But I find that general reading, both novels as well as nonfiction books about different aras of the world, has had a great impact on my writing. I’ve been fascinated in recent months to read the Cairo Trilogy of Naguib Mahfouz, the great Egyptian Nobel Prize winner. I have also been influenced by the wonderful books written by Rory Stewart, who in the immediate weeks after 9/11 walked from one end of Afghanistan to the other and wrote a book, The Places In Between, that gives you a better picture of what’s going on in Afghanistan than any other deeper, more political tome could possibly bring to you.

But I don’t think that I’ve been influenced by other travel guides.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to aspiring travel writers?

Anybody who is a talented travel writer will be discovered, and has more than adequate outlets for his writing. If a person wants to write about travel, they should immediately sit down and write about aspects of their own community. They can do a chapter on the hotel situation in Cincinnati or Milwaukee — or wherever they live — and submit that to the various travel sections of the newspapers. If it is good, it will be published. It will be seen, and you will build up enough of a dossier of published articles to obtain a job as a travel writer for magazines or for book publishers.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

The biggest reward has been the many reactions that I’ve received from the public, thanking me for the guidebooks that we’ve published for them. When people have said that the books have been of genuine aid to them — that is a very gratifying reaction to receive.