The Ironic Rise of Asia’s Abe Lincoln

By Rolf Potts

South Korean president Kim Dae-jung received a hero’s welcome from his American hosts during his recent state visit to Washington. Politicians and journalists alike made reference to Kim’s dissident days — his 10 years as an exile, his six years in Korean prisons, the five times he faced and escaped death. President Clinton compared him to Nelson Mandela, The New York Times compared him to Vaclav Havel, and Time magazine compared him to Indiana Jones.

But in the midst of all this grand rhetoric, however, nobody mentioned the most telling detail of Kim Dae-jung’s story: how he ultimately got elected. That’s because the 1997 Korean presidential election did not mesh with anyone’s giddy, marketable notions of heroism. Rather, the election amounted to a three-ring circus of sensationalism, clumsy demographic marketing and one desperate candidate trying to win points by sending his son off to work at a leper colony. Ultimately, Kim was not (as Time declared upon his inauguration) “Destiny’s Choice” to lead Korea into the new millennium, but the beneficiary of mudslinging, opportunism and circumstantial luck.

At a very basic level, Kim’s election as president of Korea has less to say about the rise of Asian-style democracy than it does about the status quo of American-style democracy.

Admittedly, it’s difficult to compare American and Korean politics. Imagine George Washington driven from office by student protests and exiled to Hawaii, John Adams and James Madison quashed by military coups, Thomas Jefferson gunned down by the CIA, James Monroe and John Quincy Adams tossed into prison for corruption, Andrew Jackson scorned for destroying the economy — and you pretty much get an idea of what Korean presidential politics have been like through the nation’s first seven administrations. Add to that a 1,500-year pre-history of regionalism, xenophobia and political violence, and it’s easy for Americans to assume that Korea’s brand of democracy was invented by a sadistic incarnation of the Ringling brothers.

But this is only because Americans prefer to think of their own democracy in terms of its feel-good myths and not its machinations. The thought of a young Abraham Lincoln reading books by candlelight in an Illinois cabin is somehow more intrinsic to our notion of democracy than George Bush mouthing “no new taxes” during an election campaign. In Kim Dae-jung, Americans have found their Asian Abe Lincoln — a man of humble beginnings who overcame adversity and became a symbol for democracy and a beacon for tolerance, inclusiveness and human dignity.

But tolerance, inclusiveness and human dignity are not what got Kim Dae-jung elected. When Kim first announced his candidacy in 1997, the Korean public shrugged. For the septuagenarian Kim, it was his fourth run at the presidency since the early 1970s, and most Koreans outside of his home province regarded him as an irritating political Energizer Bunny who didn’t know when to quit running. Early polls had him trailing ruling-party candidate Lee Hoi-chang by as much as 30 percentage points.

But, unlike previous Korean elections, the 1997 race was to center on American-style television coverage and polls — and two-crucial occurrences. First, Kim was able to exploit press reports that Lee’s two sons had evaded Korea’s military draft by shedding weight before their physical examinations. Second, Kyonggi Province governor Rhee In-je — who was a good 20 years younger than anyone else in the race and sported a flashy Elvis-like hairdo — bolted from Lee’s party and launched his own bid for the presidency. Lee’s numbers began to lag, and suddenly Kim found himself at an unfamiliar place in his long political career: at the top of the polls.

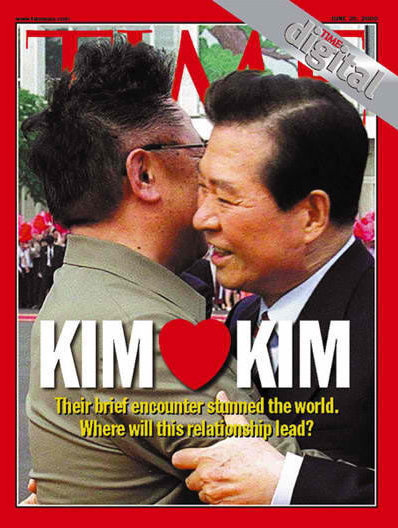

But Kim’s lead was precarious. Lee out-maneuvered Rhee by connecting him to then-unpopular President Kim Young-sam, and won sympathy points by sending his draft-dodging eldest son off for two years of volunteer work at a leper colony on Sorok Island. Seeing his lead in the polls in danger, Kim Dae-jung shocked his supporters by inviting Kim Jong-pil — an old political enemy, long thought to be connected to the attempts on his life in the 1970s — to join his ticket and serve as prime minister. This was not an act of forgiveness and reconciliation; this was a marketing stunt implemented to shore up votes with conservative voters. It almost backfired. Moderate voters noted the oil-and-water chemistry of the Kim-Kim match-up, and when the IMF currency crisis hit Korea in late November, Lee joined forces with Seoul economic expert Cho Soon. Kim’s lead dwindled to almost nothing.

With two weeks left until Election Day, Lee was poised to come from behind and win, and he publicly asked his former party colleague Rhee to drop out of the race. Rhee responded he would quit only if it was proven that Lee’s youngest son did not cheat on his military physical.

The glove had been dropped. Korea’s entire political community watched as Lee’s younger son was flown in from Boston to be measured on national television. Military records listed young Lee’s height at 172 centimeters, though that figure was later amended to 165 by an American hospital; Rhee insisted that he was no taller than 160cm, that the measurements had been fudged to up the height-to-weight ratio and win military exemption. Viewers across Korea tuned in for the big event as the young Korean removed his shoes and stood rigid against the measuring board. The cameras snapped, the audience leaned in: the tape read 164.5 centimeters. Stubbornly noting the half-centimeter discrepancy, Rhee stayed in the race and continued his accusations against Lee.

On December 18, Kim Dae-jung was elected president over Lee by a 1.6 percent margin. The western press — which had previously paid little attention to the election — had a new Asian hero. Newspapers and magazines around the world published accounts of his past resistance to dictators, of the various attempts on his life. Almost no mention was made of the back-stabbings, leper colonies and televised half-centimeters the characterized the election.

Perhaps that’s because the idiosyncrasies that got Kim Dae-jung elected were not mere sidebar news items about wacky politics in one fringe of the Pacific Rim. Essentially, Rhee In-je was to Kim as Ross Perot was to Bill Clinton; the union of Kim DJ and Kim JP as typically American as JFK and LBJ; Lee’s missing half-centimeter as trivial and devastating as Willie Horton’s weekend furlough.

Kim Dae-jung fully deserves the admiration of his American hosts. His life has been inspiring and praiseworthy. It’s just a little unsettling that — within the workings of the system he nearly died for — it took such pettiness to get him elected.

The unsung final step in Kim’s heroic rise reveals what successful American-style electoral democracy has become: a combination of shallow opportunism, marketing, chance and — buried in there somewhere — leadership.