By David M. Gross and Sophfronia Scott

[2018 companion podcast interview with Sophfronia Scott online here.]

They have trouble making decisions. They would rather hike in the Himalayas than climb a corporate ladder. They have few heroes, no anthems, no style to call their own. They crave entertainment, but their attention span is as short as one zap of a TV dial. They hate yuppies, hippies and druggies. They postpone marriage because they dread divorce. They sneer at Range Rovers, Rolexes and red suspenders. What they hold dear are family life, local activism, national parks, penny loafers and mountain bikes. They possess only a hazy sense of their own identity but a monumental preoccupation with all the problems the preceding generation will leave for them to fix.

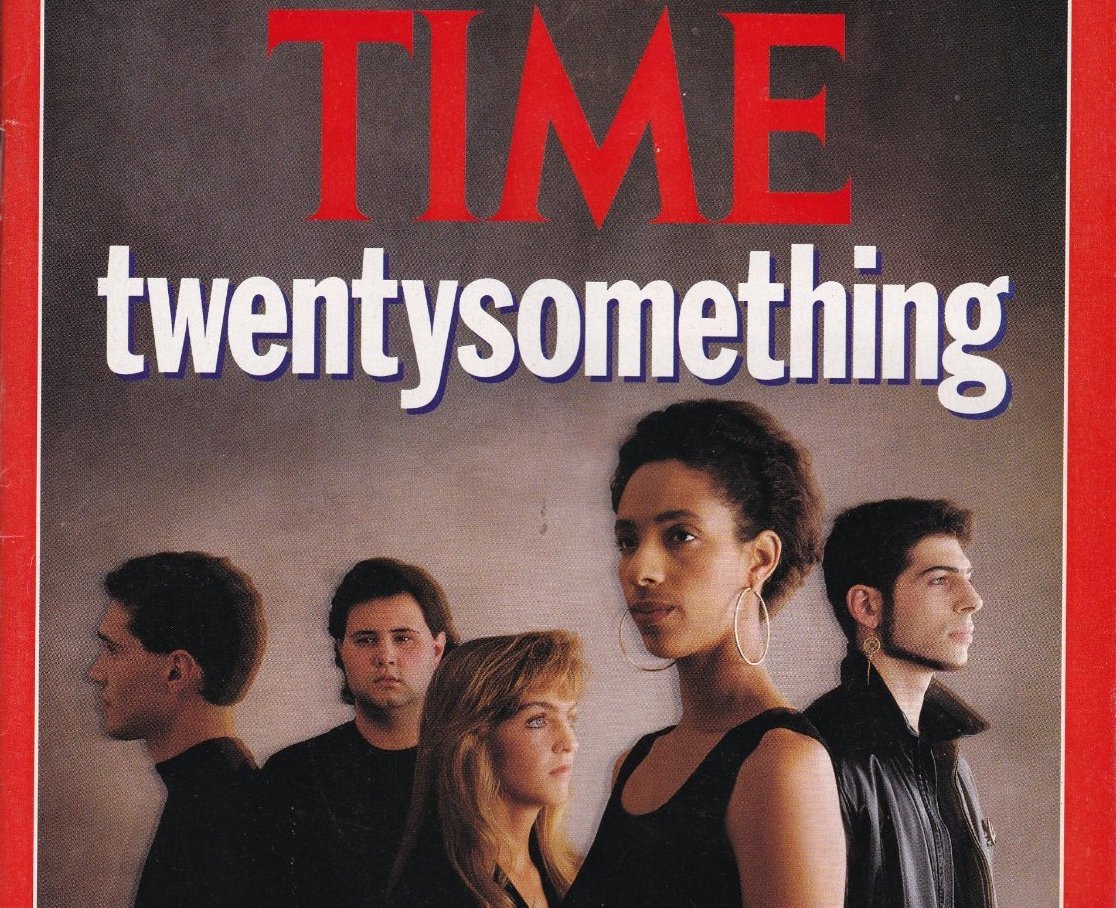

This is the twentysomething generation, those 48 million young Americans ages 18 through 29 who fall between the famous baby boomers and the boomlet of children the baby boomers are producing. Since today’s young adults were born during a period when the U.S. birthrate decreased to half the level of its postwar peak, in the wake of the great baby boom, they are sometimes called the baby busters. By whatever name, so far they are an unsung generation, hardly recognized as a social force or even noticed much at all. “I envision ourselves as a lurking generation, waiting in the shadows, quietly figuring out our plan,” says Rebecca Winke, 19, of Madison, Wis. “Maybe that’s why nobody notices us.”

But here they come: freshly minted grownups. And anyone who expected they would echo the boomers who came before, bringing more of the same attitude, should brace for a surprise. This crowd is profoundly different from — even contrary to — the group that came of age in the 1960s and that celebrates itself each week on The Wonder Years and thirtysomething. By and large, the 18-to-29 group scornfully rejects the habits and values of the baby boomers, viewing that group as self-centered, fickle and impractical.

While the baby boomers had a placid childhood in the 1950s, which helped inspire them to start their revolution, today’s twentysomething generation grew up in a time of drugs, divorce and economic strain. They virtually reared themselves. TV provided the surrogate parenting, and Ronald Reagan starred as the real-life Mister Rogers, dispensing reassurance during their troubled adolescence. Reagan’s message: problems can be shelved until later. A prime characteristic of today’s young adults is their desire to avoid risk, pain and rapid change. They feel paralyzed by the social problems they see as their inheritance: racial strife, homelessness, AIDS, fractured families and federal deficits. “It is almost our role to be passive,” says Peter Smith, 23, a newspaper reporter in Ventura, Calif. “College was a time of mass apathy, with pockets of change. Many global events seem out of our control.”

The twentysomething generation has been neglected because it exists in the shadow of the baby boomers, usually defined as the 72 million Americans born between 1946 and 1964. Members of the tail end of the boom generation, now ages 26 through 29, often feel alienated from the larger group, like kid brothers and sisters who disdain the paths their siblings chose. The boomer group is so huge that it tends to define every era it passes through, forcing society to accommodate its moods and dimensions. Even relatively small bunches of boomers made waves, most notably the 4 million or so young urban professionals of the mid-1980s. By contrast, when today’s 18-to-29-year-old group was born, the baby boom was fading into the so-called baby bust, with its precipitous decline in the U.S. birthrate. The relatively small baby-bust group is poorly understood by everyone from scholars to marketers. But as the twentysomething adults begin their prime working years, they have suddenly become far more intriguing. Reason: America needs them. Today’s young adults are so scarce that their numbers could result in severe labor shortages in the coming decade.

Twentysomething adults feel the opposing tugs of making money and doing good works, but they refuse to get caught up in the passion of either one. They reject 70-hour workweeks as yuppie lunacy, just as they shirk from starting another social revolution. Today’s young adults want to stay in their own backyard and do their work in modest ways. “We’re not trying to change things. We’re trying to fix things,” says Anne McCord, 21, of Portland, Ore. “We are the generation that is going to renovate America. We are going to be its carpenters and janitors.”

This is a back-to-basics bunch that wishes life could be simpler. “We expect less, we want less, but we want less to be better,” says Devin Schaumburg, 20, of Knoxville. “If we’re just trying to pick up the pieces, put it all back together, is there a label for that?” That’s a laudable notion, but don’t hold your breath till they find their answer. “They are finally out there, saying ‘Pay attention to us,’ but I’ve never heard them think of a single thing that defines them,” says Martha Farnsworth Riche, national editor of American Demographics magazine.

What worries parents, teachers and employers is that the latest crop of adults wants to postpone growing up. At a time when they should be graduating, entering the work force and starting families of their own, the twentysomething crowd is balking at those rites of passage. A prime reason is their recognition that the American Dream is much tougher to achieve after years of housing-price inflation and stagnant wages. Householders under the age of 25 were the only group during the 1980s to suffer a drop in income, a decline of 10%. One result: fully 75% of young males 18 to 24 years old are still living at home, the largest proportion since the Great Depression.

In a TIME/CNN poll of 18- to 29-year-olds, 65% of those surveyed agreed it will be harder for their group to live as comfortably as previous generations. While the majority of today’s young adults think they have a strong chance of finding a well-paying and interesting job, 69% believe they will have more difficulty buying a house, and 52% say they will have less leisure time than their predecessors. Asked to describe their generation, 53% said the group is worried about the future.

Until they come out of their shells, the twentysomething/baby-bust generation will be a frustrating enigma. Riche calls them the New Petulants because “they can often end up sounding like whiners.” Their anxious indecision creates a kind of ominous fog around them. Yet those who take a more sanguine view see in today’s young adults a sophistication, tolerance and candor that could help repair the excesses of rampant individualism. Here is a guide for understanding the puzzling twentysomething crowd:

FAMILY: THE TIES DIDN’T BIND

“Ronald Reagan was around longer than some of my friends’ fathers,” says Rachel Stevens, 21, a graduate of the University of Michigan. An estimated 40% of people in their 20s are children of divorce. Even more were latchkey kids, the first to experience the downside of the two-income family. This may explain why the only solid commitment they are willing to make is to their own children — someday. The group wants to spend more time with their kids, not because they think they can handle the balance of work and child rearing any better than their parents but because they see themselves as having been neglected. “My generation will be the family generation,” says Mara Brock, 20, of Kansas City. “I don’t want my kids to go through what my parents put me through.”

& That ordeal was loneliness. “This generation came from a culture that really didn’t prize having kids anyway,” says Chicago sociologist Paul Hirsch. “Their parents just wanted to go and play out their roles — they assumed the kids were going to grow up all right.” Absent parents forced a dependence on secondary relationships with teachers and friends. Flashy toys and new clothes were supposed to make up for this lack but instead sowed the seeds for a later abhorrence of the yuppie brand of materialism. “Quality time” didn’t cut it for them either. In a survey to gauge the baby busters’ mood and tastes, Chicago’s Leo Burnett ad agency discovered that the group had a surprising amount of anger and resentment about their absentee parents. “The flashback was instantaneous and so hot you could feel it,” recalls Josh McQueen, Burnett’s research director. “They were telling us passionately that quality time was exactly what was not in their lives.”

At this point, members of the twentysomething generation just want to avoid perpetuating the mistakes of their own upbringing. Today’s potential parents look beyond their own mothers and fathers when searching for child-rearing role models. Says Kip Banks, 24, a graduate student in public policy at the University of Michigan: “When I raise my children, my approach will be my grandparents’, much more serious and conservative. I would never give my children the freedoms I had.”

MARRIAGE: WHAT’S THE RUSH?

The generation is afraid of relationships in general, and they are the ultimate skeptics when it comes to marriage. Some young adults maintain they will wait to get married, in the hope that time will bring a more compatible mate and the maturity to avoid a divorce. But few of them have any real blueprint for how a successful relationship should function. “We never saw commitment at work,” says Robert Higgins, 26, a graduate student in music at Ohio’s University of Akron.

As a result, twentysomething people are staying single longer and often living together before marrying. Studying the 20-to-24 age group in 1988, the U.S. Census Bureau found that 77% of men and 61% of women had never married, up sharply from 55% and 36%, respectively, in 1970. Among those 25 to 29, the unmarrieds included 43% of men and 29% of women in 1988, vs. 19% and 10% in 1970. The sheer disposability of marriage breeds skepticism. Kasey Geoghegan, 20, a student at the University of Denver and a child of divorced parents, believes nuptial vows have lost their credibility. Says she: “When people get married, ideally it’s permanent, but once problems set in, they don’t bother to work things out.”

DATING: DON’T STAND SO CLOSE

Finding a date on a Saturday night, let alone a mate, is a challenge for a generation that has elevated casual commitment to an art form. Despite their nostalgia for family values, few in their 20s are eager to revive a 1950s mentality about pairing off. Rick Bruno, 22, who will enter Yale Medical School in the fall, would rather think of himself as a free agent. Says he: “Not getting hurt is a big priority with me.” Others are concerned that the generation is too detached to form caring relationships. “People are afraid to like each other,” says Leslie Boorstein, 21, a photographer from Great Neck, N.Y.

For those who try to make meaningful connections — often through video dating services, party lines and personals ads — the risks of modern love are greater than ever. AIDS casts a pall over a generation that fully expected to reap the benefits of the sexual revolution. Responsibility is the watchword. Only on college campuses do remnants of libertinism linger. That worries public-health officials, who are witnessing an explosion of sexually transmitted diseases, particularly genital warts. “There is a high degree of students who believe oral contraception protects them from the AIDS virus. It doesn’t,” says Wally Brewer, coordinator of a study of HIV infection on U.S. campuses. “Obviously it’s a big educational challenge.”

CAREERS: NOT JUST YET, THANKS

Because they are fewer in number, today’s young adults have the power to wreak havoc in the workplace. Companies are discovering that to win the best talent, they must cater to a young work force that is considered overly sensitive at best and lazy at worst. During the next several years, employers will have to double their recruiting efforts. According to American Demographics, the pool of entry-level workers 16 to 24 will shrink about 500,000 a year through 1995, to 21 million. These youngsters are starting to use their bargaining power to get more of what they feel is coming to them. They want flexibility, access to decision making and a return to the sacredness of work-free weekends. “I want a work environment concerned about my personal growth,” says Jennifer Peters, 22, one of the youngest candidates ever to be admitted to the State Bar of California. “I don’t want to go to work and feel I’ll be burned out two or three years down the road.”

Most of all, young people want constant feedback from supervisors. In contrast with the baby boomers, who disdained evaluations as somehow undemocratic, people in their 20s crave grades, performance evaluations and reviews. They want a quantification of their achievement. After all, these were the children who prepped diligently for college-aptitude exams and learned how to master Rubik’s Cube and Space Invaders. They are consummate game players and grade grubbers. “Unlike yuppies, younger people are not driven from within, they need reinforcement,” says Penny Erikson, 40, a senior vice president at the Young & Rubicam ad agency, which has hired many recent college graduates. “They prefer short-term tasks with observable results.”

Money is still important as an indicator of career performance, but crass materialism is on the wane. Marian Salzman, 31, an editor at large for the collegiate magazine CV, believes the shift away from the big-salary, big-city role model of the early ’80s is an accommodation to the reality of a depressed Wall Street and slack economy. Many boomers expected to have made millions by the time they reached 30. “But for today’s graduates, the easy roads to fast money have dried up,” says Salzman.

Climbing the corporate ladder is trickier than ever at a time of widespread corporate restructuring. When recruiters talk about long-term job security, young adults know better. Says Victoria Ball, 41, director of Career Planning Services at Brown University: “Even IBM, which always said it would never lay off — well, now they’re doing it too.” Between 1987 and the end of this year, Big Blue will have shed about 23,000 workers through voluntary incentive programs.

Most of all, young workers want job gratification. Teaching, long disdained as an underpaid and underappreciated profession, is a hot prospect. Enrollment in U.S. teaching programs increased 61% from 1985 to 1989. And more graduates are expressing interest in public-service careers. “The glory days of Wall Street represented an extreme,” says Janet Abrams, 29, a Senate aide who regularly interviews young people looking for jobs on Capitol Hill. “Now I’m hearing about kids going to the National Park Service.”

Welcome to the era of hedged bets and lowered expectations. Young people increasingly claim they are willing to leave careers in middle gear, without making that final climb to the top. The leitmotiv of the new age: second place seems just fine. But young adults are flighty if they find their workplace harsh or inflexible. “The difference between now and then was that we had a higher threshold for unhappiness,” says editor Salzman. “I always expected that a job would be 80% misery and 20% glory, but this generation refuses to pay its dues.”

EDUCATION: NO DEGREE, NO DOLLARS

Smart and savvy, the twentysomething group is the best-educated generation in U.S. history. A record 59% of 1988 high school graduates enrolled in college, compared with 49% in the previous decade. The lesson they have taken to heart: education is a means to an end, the ticket to a cherished middle-class life- style. “The saddest thing of all is that they don’t have the quest to understand things, to understand themselves,” says Alexander Astin, whose UCLA-based Higher Education Research Institute has been measuring changing attitudes among college freshman for 24 years.

Yet, a fact of life in the 1990s economy is that a college degree is mostly about survival. A person under 30 with a college degree will earn four times as much money as someone without it. In 1973 the difference was only twice as great. With the loss of well-paying factory jobs, there are fewer chances for less-educated young people to reach the middle class. Many dropouts quickly learn this and decide to return to school. But that decision costs money and sends many twentysomethings back to the nest. Others are flocking to the armed services. Private First Class Dorin Vanderjack, 20, of Redding, Calif., left his catering job at a Holiday Inn to join the Army. After two years of racking up credits at the local community college, he was ready for a four-year school and found the Army’s offer of $22,800 in tuition assistance too tempting to turn down. “There’s no possible way I could save that,” he says. “This forced me to grow up.”

WANDERLUST: LET’S GET LOST

While the recruiters are trying to woo young workers, a generation is out planning its escape from the 9-to-5 routine. Travel is always an easy way out, one that comes cloaked in a mantle of respectability: cultural enrichment. In the TIME/CNN poll, 60% of the people surveyed said they plan to travel a lot while they are young. And it’s not just rich students who are doing it. “Travel is an obsession for everyone,” says Cheryl Wilson, 21, a University of Pennsylvania graduate who has visited Denmark and Hungary. “The idea of going away, being mobile, is very romantic. It fulfills our sense of adventure.”

Unlike previous generations of upper-crust Americans who savored a postgraduate European tour as the ultimate finishing school, today’s adventurers are picking places far more exotic. They are seeking an escape from Western culture, rather than further refinement to smooth their entry into society. Katmandu, Dar es Salaam, Bangkok: these are the trendy destinations of many young daydreamers. Susan Costello, 23, a recent Harvard graduate, voyaged to Dharmsala, India, to spend time at the headquarters of the Tibetan government-in-exile, headed by the Dalai Lama. Costello decided to explore Tibetan culture “to see if they really had something in their way of life that we seem to be missing in the West.”

ACTIVISM: ART OF THE POSSIBLE

People in their 20s want to give something back to society, but they don’t know how to begin. The really important problems, ranging from the national debt to homelessness, are too large and complex to comprehend. And always the great, intimidating shadow of 1960s-style activism hovers in the background. Twentysomething youths suspect that today’s attempts at political and social action pale in comparison with the excitement of draft dodging or freedom riding.

The new generation pines for a romanticized past when the issues were clear and the troops were committed. “The kids of the 1960s had it easy,” claims Gavin Orzame, 18, of Berrien Springs, Mich. “Back then they had a war and the civil rights movement. Now there are so many issues that it’s hard to get one big rallying point.” But because the ’60s utopia never came, today’s young adults view the era with a combination of reverie and revulsion. “What was so great about growing up then anyway?” says future physician Bruno. “The generation that had Vietnam and Watergate is going to be known for leaving us all their problems. They came out of Camelot and blew it.”

Such views are revisionist, since the ’60s were not easy, and the revolution did not end in utter failure. The twentysomething generation takes for granted many of the real goals of the ’60s: civil rights, the antiwar movement, feminism and gay liberation. But those movements never coalesced into a unified crusade, which is something the twentysomethings hope will come along, break their lethargy and goad them into action. One major cause is the planet; 43% of the young adults in the TIME/CNN poll said they are “environmentally conscious.” At the same time, some young people are joining the ranks of radical-action groups, including ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, and Trans-Species Unlimited, the animal-rights group. These organizations have appeal because they focus their message, choose specific targets and use high- stakes pressure tactics like civil disobedience to get things accomplished quickly.

For a generation that has witnessed so much failure in the political system, such results-oriented activism seems much more valid and practical. Says Sean McNally, 20, who headed the Earth Day activities at Northwestern University: “A lot of us are afraid to take an intense stance and then leave it all behind like our parents did. We have to protect ourselves from burning out, from losing faith.” Like McNally, the rest of the generation is doing what it can. Its members prefer activities that are small in scope: cleaning up a park over a weekend or teaching literacy to underprivileged children.

LEADERS: HEROES ARE HARD TO FIND

Young adults need role models and leaders, but the twentysomething generation has almost no one to look up to. While 58% of those in the TIME/CNN survey said their group has heroes, they failed to agree on any. Ronald Reagan was most often named, with only 8% of the vote, followed by Mikhail Gorbachev (7%), Jesse Jackson (6%) and George Bush (5%). Today’s young generation finds no figures in the present who compare with such ’60s-era heroes as John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. “It seems there were all these great people in the ’60s,” says Kasi Davidson, 18, of Cody, Wyo. “Now there is nobody.”

Today’s potential leaders seem unable to maintain their stature. They have a way of either self-destructing or being decimated in the press, which trumpets their faults and foibles. “The media don’t really give young people role models anymore,” says Christina Chinn, 21, of Denver. “Now you get role models like Donald Trump and all of the moneymakers — no one with real ideals.”

SHOPPING: LESS PASSION FOR PRESTIGE

Marketers are confounded as they try to reach a generation so rootless and noncommittal. But ad agencies that have explored the values of the twentysomething generation have found that status symbols, from Cuisinarts to BMWs, actually carry a social stigma among many young adults. Their emphasis, according to Dan Fox, marketing planner at Foote, Cone & Belding, will be on affordable quality. Unlike baby boomers, who buy 50% of their cars from Japanese makers, the twentysomething generation is too young to remember Detroit’s clunkers of the 1970s. Today’s young adult is likely to aspire to a Jeep Cherokee or Chevy Lumina with lots of cup holders. “Don’t knock the cup holders,” warns Fox. “There’s something about them that says, ‘It’s all right in my world.’ That’s not a small notion. And Mercedes doesn’t have them.”

The twentysomething attitude toward consumption in general: get more for less. While yuppies spent money to acquire the best and the rarest toys, young adults believe they can live just as well, and maybe even better, without breaking the bank. They disdain designer anything. “Just point me to the generic aisle,” says Jill Mackie, 21, a journalism major at the University of Illinois. Such a no-nonsense outlook has made hay for stores like the Gap, which thrives on young people’s desire for casual clothing at a casual price. Similarly, a twentysomething adult picks a Hershey’s bar over Godiva chocolates, and Bass Weejuns (price: $75) instead of Lucchese cowboy boots ($500).

CULTURE: FEW FLAVORS OF THEIR OWN

Down deep, what frustrates today’s young people — and those who observe them — is their failure to create an original youth culture. The 1920s had jazz and the Lost Generation, the 1950s created the Beats, the 1960s brought everything embodied in the Summer of Love. But the twentysomething generation has yet to make a substantial cultural statement. People in their 20s have been handed down everyone else’s music, clothes and styles, leaving little room for their own imaginations. Mini-revivals in platform shoes, ripped jeans and urban-cowboy chic all coincide with J. Crew prep, Gumby haircuts and teased-out suburban perms. What young adults have managed to come up with is either nuevo hipster or ultra-nerd, but almost always a bland imitation of the past. “They don’t even seem to know how to dress,” says sociologist Hirsch, “and they’re almost unschooled in how to look in different settings.”

Many critics dismiss the new generation as culture vultures. But there is another way of looking at them: as open-minded samplers of an increasingly diverse cultural buffet. Rap music has fueled a fresh array of clothing styles and political attitudes, not to mention musical innovations. A new, hot radio format has evolved to provide exposure for such urban dance-music acts as Soul II Soul and Lisa Stansfield. On television, MTV has grown from an exclusively rock-‘n’-roll outlet to one that encompasses pop, soul, reggae and even disco. Like Madonna in her hit song Vogue, this generation knows how to “strike a pose.” Eclecticism is supreme, as long as the show is authentic — as camp, art or theater.

The music of the ’60s and ’70s is still viewed, sometimes resentfully, as classic. So today’s artists are busy trying to gain acceptance by reworking the past. Edie Brickell and the New Bohemians redo Dylan; 10,000 Maniacs covers Cat Stevens. Why hasn’t the twentysomething generation picked up the creative gauntlet? One reason is that the generation believes the artistic climate that existed when the Beatles and the Who were writing is no longer viable. Art, they feel, is not created for the sake of a statement these days. It’s written for money.

Even many of the fiction writers who emerged in the late 1980s — Bret Easton Ellis, Tama Janowitz, Jay McInerney, to name the usual suspects — seemed to be in it for the money and fame. That makes today’s young adults pessimistic that originals like Tom Robbins or Timothy Leary or the Rolling Stones will come along in their time. But then even the Stones are not really the Stones these days. “Kids aren’t stupid,” says Mike O’Connell, 23, of Chicago, lead singer of his own band, Rights of the Accused. “The Stones aren’t playing rock ‘n’ roll anymore. They’re playing for Budweiser.”

Maybe the twentysomething generation does have trouble making a decision or a statement. Maybe they are just a little too cynical when it comes to the world. But their realism may help them keep shuffling along with their good intentions, no matter what life throws at them. That resignation leaves them no illusions to shatter, no false expectations to deflate. In the long run, even with their fits and starts, they may accomplish more of their goals than past generations did. “No one is going to say we are anything but slow and steady, but how else are we going to go?” asks Ann Evangelista, 21, of West Chester, Pa. “I could walk this slow and steady way, and maybe I’ll end up winning the race.” For this crowd, Camelot may be a place in the future, not just a nostalgia trip to the past.

[Originally published as “Proceeding With Caution” in the July 16, 1990 issue of TIME Magazine.]