(Colonel Kurtz not included)

A journey in five parts

By Rolf Potts

Part I: Guns, muskmelon breasts and the Laotian Gandhi

Though technically communist for the past quarter-century, Laos has never really elicited Reaganesque notions of an Evil Empire.

Perhaps this is because, unlike China or Vietnam, Laos has never produced a marquee-level revolutionary (Chairman Mao and Uncle Ho had names as simple and direct as social-realist art; Kaysone Phomivane — the communist hero of Laos — sounds like the name for an experimental blood-pressure medication). Or maybe it’s because one cannot imagine Lao soldiers arming Angolan rebels, training assassins in Madagascar or crowding into amphibious landing craft off the coast of Santa Barbara.

Actually, for your average American, it’s hard to imagine Lao soldiers, period.

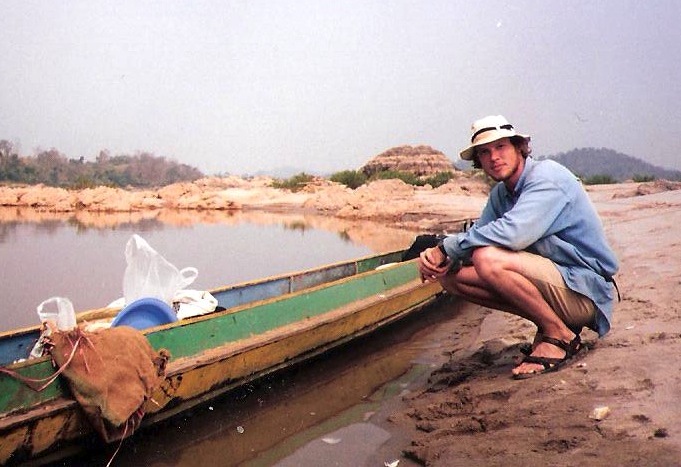

Thus, I wasn’t sure what to think when in the midst of my third week of traveling down the Mekong River, a couple of Lao soldiers rousted me out of my sleeping bag at gunpoint and marched me up the sandbar to what remained of the night’s campfire. Chris and Robert, the Americans who had masterminded this Mekong adventure, were already sitting there, smirking at me expectantly. Since I was in possession of our only Lao phrasebook, I knew what those smirks meant: I would have to do the talking.

Forcing a casual grin (the international symbol for “Please don’t shoot me”), I dug out the phrasebook and started to flip through the pages. The soldiers awaited my explanation in silence.

“Nak thawng thiaw,” I said finally. “We are tourists.”

This sent the younger soldier (who’d obviously downed a bit of rice whiskey before he showed up) into an animated rage, yelling and wildly gesturing at the boat where I’d just been sleeping. I didn’t understand a single thing he said, but I got the point. No doubt, the spectacle of Americans piloting a secondhand teakwood boat down the Mekong River must have seemed absurdly suspicious. Imagine a gaggle of Laotians blissfully riding Shetland ponies down the New Jersey Turnpike, and you get a vague idea of what it must have been like for him.

It took 15 minutes with the phrasebook — plus a half-dozen cigarettes and an entire package of sugar cookies (our treat) — before the soldiers finally gave up on us and trudged back up the riverbank into the jungle.

This came as a huge relief, since even in English I would have had a difficult time fully explaining the strange combination of circumstances that had brought me to that sandy stretch of the Mekong 100 miles east of Vientiane.

It’s quite possible that I’m the only person who has ever been inspired to travel the Mekong River after having read Mark Twain.

In “Life on the Mississippi,” which I purchased on a whim in Thailand, Twain examines a bygone time on the river that shaped his youth. Humorously comparing America’s then hell-bent railroad expansion to the glamorous steamboating days of the past, Twain reveals just how quickly technology can change the mood and attitude of a culture.

As I read this, I was taken by just how much the Mississippi River of the 1880s had in common with the Mekong River of today. Like Twain’s Mississippi, the Laotian Mekong is a dividing line, the gateway to a wild and undeveloped frontier. Like Twain’s Mississippi, life on the Laotian Mekong is just now being affected by telecommunications, land transport and electricity. Like Twain’s Mississippi, life on the Laotian Mekong is just now beginning to forget its civil-war past in favor of a more prosperous and dynamic future. Like Twain’s Mississippi, life on the Laotian Mekong is about to change forever.

I went to Laos hoping to catch a glimpse of a lifestyle that will soon be confined to history.

That, and the fact that — like countless other American males who went through adolescence in the movie culture of the 1980s — I grew up with the notion that traveling the Mekong would be as wonderfully exotic as traveling the desert planet of Tatooine, or the Temple of Doom.

Until quite recently, Laos was, like Bhutan or North Korea, strictly off-limits to adventure travelers. Granted, foreigners have been visiting Laos in small numbers since the early ’90s, but they were generally confined to government-monitored package tours and had to apply for permission to visit the more isolated regions of the country. This all changed early this year, when — in an effort to attract hard currency and open up to the Western world — Vientiane revoked longtime travel restrictions as part of its 1999 “Visit Laos Year” campaign.

Somehow I doubt this campaign was created to allow foreigners to buy fishing boats and travel 800 miles down the Mekong, but that’s OK. That wasn’t exactly what I had in mind when I arrived anyhow.

I entered Laos with the intention of hitching my way down the Mekong in local freight boats. The first of these, a small wooden outboard, took me across the Mekong from Thai territory to the Lao village of Houay Xai — the northernmost customs point on the river, just south of the Burmese border. Situated in the heart of the Golden Triangle (an area of northern Laos, Thailand and Burma that produces 60 percent of the world’s heroin supply), Houay Xai has long been an important outpost on the trade route between Yunnan, China and Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Houay Xai also marks the start of the lower Mekong, and serves as a rough midway point between the river’s mostly inaccessible Chinese course (which begins with snow-fed headwaters 15,000 feet up in the Tibetan Plateau), and its more well-known Indochina passage, which culminates in the famous Vietnamese Delta. Since the Mekong is navigable for less than 100 miles north of Laos, Houay Xai was a logical starting point for my adventure.

My first intentional act in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic was to climb the hill in the center of Houay Xai and visit Chomekaou Manirath temple, which with its water-stained walls and painted cement dragon sculptures looks like something out of a neglected 1950s-era amusement park. I’d hoped to catch a good view of the sun setting over the Mekong from the main hall of the temple, but I was instead distracted by the hall itself, which was covered with cartoonish, colorfully entertaining paintings featuring sex and violence. In one frame of the mural, a handsome young prince fends off a pack of armed attackers with his bare hands. In another frame, the prince appears to be dry-humping a beautiful young lass on the verandah of his palace. In yet another frame, the prince lounges blissfully in a bedroom full of topless female attendants, all of whom sport dreamy smiles and breasts as big as muskmelons.

Inspired, I wandered off to try to find someone to explain to me the significance of the murals. In the courtyard, a knot of saffron-robed teenage monks mixed concrete in a small metal cauldron, laughing unmonkishly and slugging each other jestfully when the gravelly gray brew accidentally spilled onto the ground. A caged monkey stared at me from his perch in a courtyard corner, then — when I stared back for too long — haughtily flopped a plastic pail over his head. Black butterflies fluttered about aimlessly. I returned to the main hall to find a young Lao couple showing the mural to their small baby. Encouraged, I pointed to the frame featuring the muskmelon-breasted women.

“What is this?” I asked them hopefully. “Who are all these people?”

The young wife just laughed and handed me her tiny son, who gurgled happily and slapped at my face as we watched the sun slide down over the Mekong.

I never found out the meaning of the murals, but it didn’t really matter anymore.

Laos has its own historical version of Gandhi, named Kommadan, who led peaceful protests against French rule in the early part of this century. Unlike Gandhi, Kommadan was also known to assassinate people. Lao history and mythology is full of such ironies and surprises.

I learned about the Lao Gandhi on the morning of my second day in Houay Xai, from a young schoolteacher named Xouliphone, whom I’d originally befriended in the hope that he would help me find a passage on the freight boat downriver. Xouliphone did indeed find me a freight boat, but not before spending three hours aimlessly showing me around town and chatting me up. Lao people, I discovered, are rarely in a hurry to do anything.

“Houay Xai Upper Secondary School has 698 students,” Xouliphone told me as we walked along the school’s parking lot, which was packed with nearly identical purple and red Flamingo Sportcycles; “294 of them are girls.”

“Wow,” I replied politely.

“Houay Xai Upper Secondary School has 22 teachers,” he said. “Nine are women. And we have four typewriters.”

“Interesting,” I said.

But none of this was really all that interesting until Xouliphone told me about the Gandhi who assassinated people.

Like so many people from Lao lore (including Sikhot, the Lao Achilles — whose Achilles heel was in fact his anus, because he met his doom when an assassin hid out in his pit latrine), Kommadan is a quirky, tragic figure. Kommadan — who actually was not an ethnic Lao, but a hill tribesman from the southern mountains of Laos — started his resistance to French rule with a series of assassinations and armed raids on southern villages in 1905. Kommadan’s major bone of contention was the colonial French policy of forced taxation, forced labor and forced resettlement.

When Kommadan’s armed raids met with indecisive results, he changed strategies and launched a peaceful letter-writing campaign in 1908, imploring the French to give his people a voice in the political process. Kommadan’s letters eventually resulted in an official meeting with Jean-Jacques Dauplay, the local French commissioner, late in 1910. Had Kommadan been keeping up on his recent history, he never would have agreed to meet with Dauplay: One year earlier, the same French official had invited a Lao rebel chief named Bac Mu to his house under the pretense of viewing photographs; once inside, Bac Mu was summarily bayoneted to death.

Kommadan encountered a near rerun of this diplomatic strategy in 1910, when — 10 minutes into their negotiations — the French commissioner nonchalantly picked up his Browning rifle and began to pump the Lao Gandhi full of bullets. Kommadan barely escaped with his life, and, when his wounds had healed, returned to the business of armed raids and assassinations. Kommadan lived like a Pancho Villa-style outlaw for the next 25 years, hiding out in the mountains and stirring up anti-colonial, anti-taxation sentiment. In 1926, he resumed his letter-writing campaign, this time calling for a written statute of what today would be termed minority rights. His letters addressed reconciliation and diplomacy, but for some reason he couldn’t break his habit of assassinating people. He was finally hunted down and killed by Vietnamese mercenaries in 1936.

After relating the story of Kommadan, feeding me lunch and telling me more statistical information than any sane person needs to know about Houay Xai Upper Secondary School, Xouliphone found me passage downriver to Pak Beng on a boat loaded with Sprite, Pepsi, floor tiles, laundry detergent, Chinese cookies and three old ladies. I could have kept things simple and taken the tourist ferry, but I wasn’t in a hurry and I wanted to try something different.

The three old ladies had a boombox and gave me my first exposure to Lao pop music, which sounds torturously similar to a sack-full of cats cascading downhill to a synthesized backbeat. On a more pleasant note, they’d brought a basket full of bananas, and they thought it was infinitely funny that I could eat so many of them. They also found it a real hoot when I took out my Lao phrasebook and (unsuccessfully) tried to make conversation with them. I ultimately gave up and climbed out onto the tin-sheeted roof of the boat to watch the river go by.

This type of diesel-powered freight boat, called “huahoua-liem” by the Lao, operates on an apprentice-pilot system not unlike what Mark Twain experienced on the Mississippi. The older pilot sits at the front of the 60-foot craft in a small cabin and mans the wheel, while the cub pilots sit in the back to heft freight, bail water, maintain the engine and — presumably — learn the river’s routes and dangers. Officially, Laos’ roads now move more freight than the Mekong (the last time the river out-hauled the road was in 1991), but these river pilots have job security in the steady downriver commerce (much of it illegal) from Thailand and China to the old royal capital of Luang Prabang.

Originally, the French had hoped to compete with British Hong Kong by using the Mekong as a backdoor trade route to China, but this was proved impossible by the Francis Garnier Mekong expedition of 1866-68. Garnier, a hardy 26-year-old French naval officer who deserves a place among the great explorers of the 19th century, spent two years on the river before finally reaching China, even though his trade officer concluded as early as the cataracts of northern Cambodia that “steamers can never plough through the Mekong, as they do the Amazon or the Mississippi, and Saigon can never be united to the western provinces of China by this immense riverway.”

Ultimately, attempts at economically exploiting the Laotian Mekong were a flop for France, as Laos accounted for only 1 percent (and most of that opium) of France’s foreign trade in Indochina.

Because of the Mekong’s failure as an international superhighway, it is one of the very few great rivers of the world that retain a somewhat pristine character. As I sat on the tin roof of the boat, I took in sights that probably hadn’t changed much since Garnier arrived 133 years ago: rattan-and-thatch homes clinging to hillsides at the high-water mark; smiling locals cooly navigating rapids in dugout canoes; sarong-wrapped women bathing beneath black-rock cliffs at sundown; naked, sunbrowned kids clowning around in the shallows, gleefully calling out to me as I drifted by, long and pale atop my riverboat.

However, “pristine” is a purely relative term here at the end of the 20th century. Whereas the Garnier expedition described the Laotian wilderness as an “unending, unpenetrable forest,” the land I saw from the riverboat was marred with countless stretches of smoldering burn-off and deforested clear-cuts. The burn-off is the result of traditionally practiced “shifting cultivation” (as of 1990, 1 million Lao still practiced slash-and-burn agriculture), but the clear-cuts are evidence of a more recent phenomenon: Thai loggers, who began to exploit Lao forests when Thailand banned commercial logging a decade ago. Three hundred thousand hectares of Laotian forest are lost annually, despite recent government efforts to reduce both shifting cultivation and foreign logging interests.

The most obvious result of this deforestation is the lack of wildlife. Whereas Garnier reported seeing all manner of tigers, leopards, wild elephants, monkeys, crocodiles and boa constrictors haunting the shores of the Mekong, all I noticed was a smattering of birds and insects.

Just before dark, our riverboat pulled into the village of Pak Beng, which is perched on a steep slope overlooking a gorgeous, canyon-like stretch of river. In 1997, Pak Beng featured three guesthouses; by the time I arrived, that number had grown to 15 — all of them built to house the “Visit Lao Year” onslaught of backpackers headed up or downriver between Luang Prabang and Houay Xai.

Despite the hotel boom, Pak Beng still resembles a dusty cow-town from some Wild West movie, right down to the splintered wood-slat sidewalks, the storefront dry-goods shops and the squint-eyed, cheroot-smoking locals. My hotel room cost a dollar, opened with a skeleton key and didn’t have electricity or running water. The only restaurant in town with an English-language menu featured “Minced Skin With Sliced Paper” and “The Fried Insides of a Hen.” After dark, barefoot little boys shyly sidled up to me in the street and whispered “O-pee-umm?” If I didn’t immediately react, the little boys would wink and pantomime taking a hit from a hookah.

The chickens of Pak Beng ran wild in the streets and screamed all night like the tortured souls of murderers. I didn’t get much sleep.

Too tired the next day to look for freight boats, I departed for Luang Prabang on the tourist ferry, which contained five Americans, two Norwegians, six Hmong hill tribespeople, 20 sacks of rice and one hog-tied hog. I’d had the intention of climbing atop the roof of the boat to look for elephants and stare out at the karst limestone formations, but the Americans and Norwegians proved too entertaining. Sometimes the best-laid plans are undermined by simple camaraderie: I spent most of the Pak Beng-Luang Prabang transit drinking whiskey, playing spades and trading inane pirate jibes (“Shiver me timbers!”) with my fellow travelers. We made Luang Prabang by nightfall.

Had I been any better at talking to women, and had an Italian traveler not bled to death in a Luang Prabang hospital, and had a Paklay restaurant owner not made such a big display of seating me at an outside table one Friday morning, my Mekong travel might well have ended there.

Such were the odds that eventually landed me on a rickety secondhand fishing boat with two Americans headed downriver.

Part II: Bliss (and death) in Luang Prabang

Luang Prabang is perhaps one of the worst-kept best-kept-secrets in the world. It is a miracle that it has not yet been overrun with wide-eyed New Age seekers, utopia-obsessed dropouts and profit-crazed resort developers.

Every significant scrap of Southeast Asian travel literature in the last 130 years, it seems, has contained raves about Luang Prabang’s sublime wonders — from Louis de Carne’s 1866 Garnier expedition journal (“Luang Prabang has been to us what an oasis is to a caravan wearied by a long march”) to Marte Bassene’s 1909 Laos travelogue (“Luang Prabang is in reality a love, a dream, a poetry of naive sensuality which unfolds under the foliage of this perfumed forest”) to Norman Lewis’ classic 1950 travel book “A Dragon Apparent” (“Luang Prabang … is a tiny Manhattan, but a Manhattan with holy men in yellow robes in its avenues, with pariah dogs, and garlanded pedicabs carrying somnolent Frenchmen nowhere, and doves in its sky”). Even the famed French naturalist Henri Mouhot, who spent his entire 1861 stay there slowly dying of malaria, called Luang Prabang “a delightful little town.”

Add to this the 1999 words of an 18-year-old Canadian backpacker I met my first night there: “Luang Prabang is like a Disney creation or something. But the cool part is that it isn’t.”

Surrounded by mountains and as isolated from the rest of the world as Tibet or Kashmir (until recently, the only safe and dependable year- round way to get there was by airplane), Luang Prabang was the seat of the first independent Lao kingdom (Lane Xang) in the 14th century, and was off and on a royal capital for 600 years prior to the Communist takeover in 1975. It features wood-shuttered Lao-French colonial architecture, over 30 Buddhist temples, hill-tribe women selling embroideries under peeling Communist murals in the market and pack-dirt streets lined with palms and red dust. UNESCO declared the town a World Heritage site in 1995.

But the appeal of being in the city itself is so visceral that accolades and honors do it little justice. Luang Prabang is a hedonist’s city, not in the sexual sense (although it would be a wonderful place to have a love affair) or in the chemical sense (although opium and marijuana are available in the same way that pan-fried chicken is available in Kansas City) — but rather in a sense of blissful, inspired sloth.

From nearly the moment I stepped off the slow ferry from Pak Beng, Luang Prabang moved me to new heights of inaction. I found myself spending entire evenings there chatting aimlessly with the locals, eating baguette sandwiches, looking for the perfect watermelon shake, watching Orion glitter above the golden stupa on Phou Si (“Marvelous Mountain”) or just happily staring off into space at one of the sidewalk cafes on Sisavangvong Avenue.

My one concession to industriousness was to visit the pier each morning and check for freights headed downriver to Paklay, the last major outpost on the Mekong above Vientiane. The customs officer there was a toothless, delightfully gregarious old guy whose voice sounded like a raspy phone connection from some technologically limited Micronesian principality. Sitting in his metal folding chair — his shock of white hair sticking straight up, a cigarette smoldering in his fingers — he looked like a Lao version of Samuel Beckett.

“You must wait for a freight boat,” he rasped the first time I visited the customs house. “The water is too low today. The river to Paklay is very dangerous.”

“How long do I have to wait?” I asked him.

His eyes glittered mischeviously. “Three months,” he said. “Maybe two months if there is good rain.”

After some more banter and a few cups of cold tea, Beckett conceded that there was one possible way to find passage downriver. “You can pay a speedboat boy to take you to Paklay,” he said. “The river is not safe, but the speedboat boys don’t care when you give them money. They are foolish.”

I knew what he was talking about. I’d seen the speedboats blasting up and down the river since I’d started my journey at Houay Xai. Light, knife-like and low in the water, Mekong speedboats sport huge long tail engines and sound like jet airplanes. Everyone on board is required to wear helmets, since the boats can reach upwards of 50 miles per hour.

I’d hated the speedboats from the moment I’d first seen them: They were reckless and infuriatingly loud, and they made their helmet-coiffed passengers look like some sort of ridiculous commando squad from the cartoon “Speed Racer.” Nonetheless, they appeared to be my only option.

“Can you help me find a speedboat to Paklay?” I’d asked Beckett.

The old customs officer frowned. “The speedboat boys are very foolish. Maybe a bus is better.”

The idea of bus travel was to me as aesthetically obscene as tugboat commerce was to Mark Twain: I was in Laos to travel the Mekong, period. “But I am very foolish, too,” I said. “Can’t you help me?”

Perhaps sensing a bit of profit in it for himself, the customs officer relented. Each morning I would go down to the pier to chat with him and check on speedboats. Unfortunately, the “speedboat boys” were not as foolish as old Beckett let on: Except for one driver who wanted a non-negotiable fee of $200 for the service, nobody was willing to take me downriver at low-water. After four days, I was beginning to get a bit nervous.

It was about this time that I ran into Suki, a Dutch girl with whom I’d shared a hotel room back across the border in Chiang Khong, Thailand. Suki is one of numerous females in my life that I never got to know romantically because I am inherently bad at talking to women.

Indeed, instead of being engaging and flirtatious in the face of a potentially romantic situation, I usually get tied up in pointless verbal displays of existential worthiness. Whereas the true seduction artist can sense the right moment to suggest a moonlight walk or a back rub, I just go on babbling awkwardly about travel experiences, Beat-era literature or how I can run 400 meters in 50 seconds.

In Suki’s case, I got off on a tangent about my plans to travel the Mekong — and at one point suggested that I might buy my own boat once I got to Laos, since I had acquired a bit of river-running experience in the United States. Two weeks later, this inane comment paid off.

“I met an American named Robert who also wants to buy a boat!” Suki had told me when I unexpectedly ran into her at Luang Prabang’s central market. “Do you want to meet him?”

Unlike so many other parts of Southeast Asia, Laos does not attract travelers who think “seeing the world” has something to do with playing putt-putt golf, taking ecstasy or purchasing the services of a hooker. The cross-section of wanderers I met in Luang Prabang was a perfect example of this.

Whereas places like Bangkok, Phuket or Bali are stocked with a steady rotation of Westerners on two-week stints of recreation and mild decadence, Laos attracts adventure-seekers who travel for months or years at a time. In my first four days in Luang Prabang I met a Canadian whose most recent job had been prospecting diamonds in the Yukon, an American who’d funded a year of travel by working in a Las Vegas chocolate factory, a Frenchman who was in his seventh month of motorcycling around the world, a New Yorker who’d quit his job as a stockbroker the moment he’d learned how to surf and two separate people with concrete plans to work in Antarctica.

Since Luang Prabang makes a good staging area for exploring the mountainous northern reaches of Laos, everyone had some sort of plan to break out of the standard tourist circuit. Some people were headed for the Plain of Jars (the Lao answer to the statues of Easter Island: a grassy plateau scattered with — you guessed it — enormous, mysterious stone jars); others wanted to explore the remote cave network of Vieng Xai (built by the Communist Pathet Lao in response to U.S. Gen. Curtis LeMay’s plan to “bomb the enemy back to the Stone Age”); yet others had their sights set on the budding postmodern opium dens of Muang Sing.

By the time I’d located Suki’s acquaintance Robert — an Alaskan salmon fisherman who’s spent every winter for the past 15 years traveling in third world countries — he’d already purchased a fishing boat named Mik Sip (which was small enough to handle the shallows to Paklay) and prepared it for a downriver voyage. What’s more, he’d already found four other people to go with him.

“Can you fit a sixth person?” I’d asked him hopefully.

“No,” said Robert (who — in keeping with his calling as an Arctic fisherman — was rarely long on words).

Robert and the Mik Sip set off down the Mekong the following morning. I resumed my happy routine of eating coconut ice cream, wandering sleepy back-streets at dusk and indulging in $1 herbal steam baths at the local Red Cross building. My morning visits to find a downriver speedboat continued to get me nowhere.

Then horror struck. On the morning of my seventh day in Luang Prabang, I arrived at the customs house to find Beckett in such a huff he could barely talk. “Foolish!” he rasped, showing none of his usual ironic cheer. “Very bad! Very very very bad!” He accusingly shook his finger at nothing in particular.

I finally got it out of him that there had been an accident: an upriver speedboat had hit a rock at full speed, killing the driver instantly. The passengers — all of them foreigners — were on their way to the hospital. It didn’t look good.

Rumors spread quickly in a travel community; I won’t even bother repeating what I heard about the accident the day it happened. Everybody was worried, of course, but nobody knew what was going on.

Twenty-four hours after the accident, I knew this for certain: An Italian traveler had suffered massive head injuries from the crash, and — in the main hospital of the third most populous city in Laos — nobody could locate a doctor. Nurses arranged a hasty blood transfusion, but by the time the doctor arrived four hours later, the Italian was dead. The other victims of the crash — two Norwegian girls — were expected to live, but both had spinal injuries.

Abandoning forever the notion of hiring a speedboat downriver, I swallowed my pride, went to the bus depot and bought a ticket for Paklay.

Part III: A lucky break in Paklay

Bus travel in Laos (to use a word popular when I was in junior high) sucks.

Had my transit from Luang Prabang to Paklay been 30 minutes long and featured loudspeakers blasting Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” it might have been bearable — even entertaining. Unfortunately, my breakneck plunge into the nether boondocks of Sayaburi province lasted all day and featured a nonstop barrage of Lao pop music that sounded like a racquetball court full of drunken little girls incoherently scolding pet chinchillas to a synthesized backbeat. I suffered woefully.

When I first boarded the small bus (actually, an old Russian truck with wood-slat benches) — a vehicle which under any rational code of comfort and sanity could fit 15 people — I was amazed to discover that the Luang Prabang bus authority had sold tickets to 32 people. Since there were no other Westerners on board who could share my dismay, I took out my notebook and wrote the number down: 32. Chagrined, I circled it for emphasis.

One hour later, there were 45 people (and numerous chickens) crammed into the bus, and I could no longer move my arms to reach my notebook.

Laos (a country the size of Great Britain) has only 2,100 miles of tarred roads. None of these tarred roads, apparently, are located southwest of Luang Prabang. Nevertheless, our bus driver navigated the dusty highway with a hell-bent sense of speed lust that would have been impressive if it hadn’t been so terrifying. I found myself flushed with relief when (because there is no bridge) we had to leave the trucks and load into boats to cross the Mekong. On the other side, all 45 of us (not counting chickens) crammed into a nearly identical truck with a nearly identical driver.

If the peanut fields and hardwood forests of Sayaburi province are as enchanted as the pleasure domes of Xanadu, I’d have no way of knowing: From mid-morning to dusk, my day went by in a fish-tailing rush of billowing dirt, screeching chickens and blurred scenery.

Once I’d arrived in Paklay and checked into a guesthouse, I immediately staggered down to the river. Although I’d roughly been following the Mekong valley all day on the buses, I wanted to sit still for a moment — to center myself with the quiet beauty of the water itself. The riverside was full of sarong-wrapped bathers at sundown; I stripped down and joined their ranks. The hills of the far shore glowed with late-day brush fires.

Paklay is an old French garrison town that owes its existence to the river. Located on the southwestern-most bend on the Mekong above Vientiane, it served for years as the point where land caravans from Bangkok unloaded their goods into boats up- and downriver. It was little more than a frontier outpost for the French, and it still wasn’t much when I visited. “If commerce were in any way active,” Bassenne wrote in 1909, “this poor village would soon grow. But it is still in an embryo state.” Considering that Route 13 from Luang Prabang to Vientiane via Vang Vieng is now completely paved (thus rendering the river route impractical), it’s likely that Paklay will remain in an embryo state indefinitely.

As I was splashing around in the gentle shoreside currents of the Mekong that evening, a couple of young Lao guys jogged down into the water and practically dragged me out onto dry land. At first I thought I’d been doing something wrong, but they soon made it clear that they just wanted me to drink with them. A bottle of rice whiskey was procured, and we were toasting each other’s health before I’d even dried off. Considering that we were so close to the pier, I optimistically assumed that the fellows were river pilots who’d like nothing better than to take me down the river the next day. As it turned out, they were truck drivers.

We drank hearty anyhow. Since they didn’t know much English and I didn’t know much Lao, we prefaced each toast by counting in each other’s language.

“Three, four, five, six, seven!” the truck guys would yell.

“Sam, sii, ha, hok, jet!” I would reply, and another round of high-octane rice whiskey (“a liquor so strong as to destroy the taste” reported Garnier in 1866) would go down the hatch.

I report with pride that I was the last one to vomit that evening.

The following morning I reported to the customs house at the pier and was told that the river was too low for the huahoua-leim freight boats.

“But you can pay for a speedboat!” the Paklay customs officer told me brightly. I retreated into town to eat a baguette and mull this over.

At the restaurant, the owner made a big show of seating me at an outside table in view of his (presumably jealous) neighbors. He proudly presented me with his English-language menu, which featured such delectable dishes as “Prawn Soaking Fish Sauce” and “Sour Soup Skid and Prawn.”

Entrees aside, the most interesting detail about the menu was that it had been made from an old communist children’s book. On the cover (which now read “MENU” in blue Magic Marker) was a sentimentalized drawing of Lenin, looking beatific and suspiciously Jesus-like, surrounded by adoring children. The pages inside had been torn out and replaced with a laminated menu card that listed prices in Lao kip, Thai baht and U.S. dollars.

Communism is unraveling, it seems, in the dusty corners of Laos.

Halfway through my baguette, I looked up to notice two Americans staring at me from the street. The sandy-haired one, who introduced himself as Chris, held a plastic jug full of cherry-red gasoline. The other one was Robert. He said, “Still interested in going down the Mekong with us?”

I would later discover that half of the Mik Sip crew had turned up sick and couldn’t make the trip, but at that moment I didn’t even ask why I’d been invited: Within 20 minutes, I had purchased some food and a blanket and was stretched out languorously in the bow of the boat that would eventually take me to the Cambodian border.

Traveling downriver in a handmade fishing boat makes the Mekong seem so much more immediate and alive. From the bow of the Mik Sip, I noticed details that I had missed on the larger, louder huahoua-leim freight boats: white-bellied birds darting for insects just over the surface of the water; slowly rotting skeletons of huge old riverboats in the shore mud; ashes from slash-and-burn fires fluttering through the air like brittle black feathers; butterflies as big as my hand. Fishermen clung to the rock outcroppings where the channel of the Mekong narrowed to a boil, sweeping the foamy water with their big, V-shaped nets. Lao families panned for gold on the gravel shoals, using a wicker-basket/wooden-pan technique that hasn’t changed in 100 years. Dead dogs bobbed — bug-eyed, bloated and morbidly comical — in the eddies.

Robert steered us through the channels of the Mekong like he’d being doing it all his life (with Chris spotting pylons with the binoculars, Robert unflinchingly ran a rapid that had swallowed a French gunboat in 1910). Whenever we lost a propeller to rocks or gravel, Robert and Chris would curse, paddle us to shore and have a new one jury-rigged within minutes. Both of these guys would eventually teach me the ways of the river, Mark Twain-style — Chris with the cantankerous patience of Captain Bixby; Robert with the no-nonsense bluntness of Captain Ahab.

Just after sundown, we stopped for the night at a sandbar. Robert’s years of experience on Bristol Bay gave our camp a decided air of competence and efficiency: In the fading light, he managed to pound 20 nails into the gunnels of the Mik Sip, grease the drive shaft, top off the engine oil, build a fire and cook us a dinner consisting of baked potatoes with garlic, coconut-milk vegetable curry, cucumber salad, French bread with cheese, oranges, papayas, Lao whiskey and cowboy coffee.

During dinner, Chris — a Nevada City carpenter of indeterminate age (I’d thought he was just a few years my senior until he offhandedly mentioned that he’d joined the Navy the year I was born) — kept us entertained with old road stories, such as the time when his Colorado River rafting guide stripped naked and declared himself God after eating a wild mushroom, or the time he saw a cow tumble 1,000 feet down a Peruvian mountainside.

After we’d finished eating, Robert tuned in his shortwave radio and we listened to Orson Welles’ famously constipated rendering of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which for some reason was playing on the Voice of America. Sitting on the banks of the Mekong in Laos, it sounded creepy and mesmerizing, like a transmission from another galaxy.

The following day we made it to Vientiane — a national capital so unassuming and bucolic that, thinking it just another Lao Mekong town, we passed it by accident and had to backtrack seven miles before we finally arrived.

By the time I would leave the Laotian capital, I would be the co-owner of the Mik Sip — and the primary instigator of a rather foolhardy conspiracy to take the boat down the most notorious rapids on the Laotian Mekong.

Part IV: In Vientiane, a lull before the storm

When explorer Francis Garnier arrived in Vientiane in 1866, he was amazed by the extent to which the city, which had been pillaged and razed by the Thais just a few decades earlier, had already reverted to jungle. He wrote, “The absolute silence which reigned in the enclosure of a city that formerly was so populous and so wealthy astonished us.”

One hundred thirty-three years later, the silence that astonished Garnier has not entirely gone. Walking through the Lao capital, one gets the feeling that if the government one day decided to relocate the entire population to Coconut Grove, Fla., Vientiane would revert to dust and vines in a matter of weeks. In no other Asian capital is a traveler more likely to share a sidewalk with a water buffalo, fall into an open sewer within view of the Presidential Palace or get a quiet night’s sleep.

But while I was in the drowsy Laotian capital, I once again encountered a set of obstacles that halted my progress and threw my Mekong travels into uncertainty.

By far the biggest obstacle was that, for various reasons, Robert and Chris had to leave Laos and Vientiane was the ideal place to do that. This posed a grave problem for me, since we had yet to navigate the dreaded Khemmarat rapids below Savannakhet — and I knew just enough about driving the Mik Sip to kill myself and everyone onboard in a very inefficient and undignified manner.

Each night during our Vientiane layover, I would meet with Robert and Chris over dinner to propose and discuss different options for extending our Mekong travels. As is perhaps natural with people who have been living on a boat, we were so taken with the novelty of civilization that we really didn’t care which civilization it was. On various nights, we convened for Pizza Reine at La Provengal restaurant, mint curry and lassi at the Taj restaurant and bacon double-cheeseburgers at a place called Uncle Fred’s Country Chicken.

In the daytime, I cruised the city for 30 cents a day on a decrepit, undersized, one-speed “Hare Sport” — the kind of bicycle a person rents from his guesthouse only when there are no options. I spent hours rattling my way over Vientiane’s dusty, rock-strewn streets.

Everything in Vientiane, it seems, is either under construction or falling apart. When I first arrived, I was pleased to discover that my visit coincided with the Tet holiday; unfortunately, the celebration was hampered by the fact that all the streets in Chinatown had been torn out for repaving. I visited the monstrous concrete Victory Arch (nicknamed the “Vertical Runway” because it was built with cement donated by the United States in 1969 for airport construction), only to find it partially closed off because the upper viewing decks — which from the inside resembled a condemned YMCA handball court — were beginning to crumble.

By far the liveliest place in Vientiane was the morning market, where amid crowded stalls offering Lao weavings, gold jewelry, Ray-Bans, shampoo, fake Nike apparel and Vietnamese sugar cookies. Scores of middle-aged ladies prowled the aisles with bags full of Lao currency, accosting foreigners and offering to exchange for dollars at 50 percent better than the bank rate. When I asked one lady if she accepted traveler’s checks, she said, “Yes, but only if you write down the same name as the one on the check.” Needless to say, she didn’t ask for my passport.

By contrast, the women working at the government bookstore on Setthathirath Avenue were literally asleep behind the counter when I arrived, and seemed confused when I wanted to buy something. Communist-themed comic books lined the bookstore’s back wall, and copies of the hopelessly non-controversial Vientiane Times (sample front-page headline: “Non-aligned movement adopts stance on global issues”) sat stacked by the front door. On the glassed-in display shelves — just across from the Marx, Lenin and Kaysone Phomivane posters — sat new English-language titles like “Markets and Development” and “Entrepreneurship”: evidence that the current leaders of Laos are beginning to allow the inevitable.

Historically, Lao leaders have had a knack for acting more out of impulse or bravado than calculated common sense. In 1550, for instance, King Potisararat was crushed to death while attempting to impress a group of visiting ambassadors with his elephant-lassoing skills. In 1817, a pagan priest named Ai-Sa briefly seized the southern royal palace at Champassak through his fearsome power to create fire; when it was later discovered that he’d merely been using a magnifying glass, he was run out of town.

But perhaps the most well-known story of Lao derring-do dates back to 1478, when the governor of Kenetha captured a rare white elephant and gave it to King Chaiya. Impressed by news of this rare find, the emperor of Vietnam dispatched a delegation to ask for a few tail hairs from the sacred beast. The Lao king’s son, who didn’t care much for the Vietnamese, sent the delegates home with a box full of the elephant’s feces. War ensued. Luang Prabang was sacked.

By comparison, today’s communist leadership, with its gradual concessions to tourism and open markets, seems downright dull. But perhaps this is because, after a few hundred years of being dominated by the interests of either Thailand, China, France, the United States or Vietnam, the leaders of Laos want to choose a more deliberate, self-determined path for their country.

Efforts at development in Laos have been slow at best. Construction is set to begin this summer on a nine-mile railroad link to Vientiane from Nong Khai, Thailand. Once this project is completed, Laos will have increased its total number of rail miles built this century to a whopping 12. Also on the docket this year is the expansion of Dansavanh Resort and Casino north of Vientiane. According to a somewhat telling Bangkok Post interview with resort developers, attractions at the Dansavanh will include parasailing, karaoke and “not getting malaria.”

Not surprisingly, the Mekong and its tributaries are the biggest weapons in Laos’ economic arsenal. According to “What and How to do Business in the Lao PDR” (one of my purchases from the sleepy ladies at the government bookstore), the biggest development potential in Laos lies in hydroelectricity. River-generated electricity is already Laos’ No. 1 export; sources estimate that the Lao Mekong basin could one day generate electricity equivalent to the energy in 1 million barrels of oil a day. Optimists have nicknamed Laos the “hydroelectric Kuwait” of southeast Asia, an ironic moniker for a country where most villages don’t have electric power and old-fashioned flame-torches are still sold in the markets of the capital. To date, no dams (and only one bridge) have been built on the Laotian Mekong itself, but plans to construct a reservoir 12 miles upriver from Vientiane have been on the table since the 1960s.

If constructed, this dam would alter the commerce, agriculture and ecology of the Mekong in a manner unparalleled in its history.

After five days of maneuvering in Vientiane, Chris had successfully extended his visa and talked his friend Terry into joining the crew; Robert had convinced his girlfriend Sarah to forgo their Thailand beach rendezvous and meet up with us in Laos; and I had purchased a share in the Mik Sip with the intention of learning how to drive it and taking over when everyone else had left. Within 12 hours of Sarah’s arrival at the airport, we were back on the river.

Downstream from Vientiane, the Mekong widened to the size of a New England lake, its current slow and muddy. Even near the capital, every inch of dry-season alluvial soil was planted with vegetables. In some places, the alluvium had broken away from the riverbank, leaving dozens of tiny, tomato- or corn-covered islands standing forlornly out in the brown current. On the shore, Lao schoolchildren on their lunch break shucked their uniforms and swam in the shallows; others raced down the grassy riverbank on makeshift sleds fashioned from cardboard boxes. At the edges of the sandbars, thousands of tiny brown frogs jittered like popcorn whenever we splashed ashore.

Since I was now part owner of the boat (and would have to fill Robert’s place in seven days to somehow assist Chris through the Khemmarat rapids), I gradually began to learn how to pilot the Mik Sip. The more I drove the long teakwood boat, the more I came to realize what kind of dangers the journey would present.

From a passenger’s perspective, the Mik Sip had seemed to glide through the river without much effort. But once I took my place behind the engine, I realized that our peeling, yellow-painted boat was anything but a precision machine. The rudder, for instance, had been fashioned from a flattened coffee can and was held in the prop-wash by a spacer made from a rubber flip-flop sandal. The throttle lever had long since broken off and had been replaced with a creatively lashed triangular file. The tip of the drive shaft was stripped of its threading, and the propeller was held in place with twisted wire. The bail was a creatively scissored oil jug, and the depth-sounder was a bamboo pole.

Fortunately, the 300-mile stretch of river above Savannakhet was wide, slow and sandy — a perfect beginner’s course.

With easy waters and a lively five-person crew, our transit downriver came to resemble a blissful, goal-less elementary school summer vacation. During the day, those who weren’t driving would chat or read or doze in the front of the boat. In the evenings we would set up camp on a sandbar, cook tremendous dinners and share stories or tell jokes over the campfire.

Though we slept in the sand, we dined like kings: steamed green beans and baby corn in butter; potatoes baked with garlic, garnished with crushed red peppers; French bread with cream cheese and tuna; roast chicken with sticky rice and soy sauce; pumpkin, carrot and potato stew thickened with ramen noodles; fresh cucumbers, onions and tomatoes, diced up along with hard-boiled eggs and seasoned with lime and vinegar; papayas, bananas, lamoot, watermelon and mandarin oranges for dessert. One morning, Robert gill-netted four fish and cooked them for breakfast. Each night, Terry mixed us “Mekong-and-Mekhong” cocktails, made from boiled river water and the eponymous Thai whiskey.

We came to enjoy our simple lifestyle so much that we weren’t even that demoralized when Lao soldiers showed up at our beach camp to roust us out of bed at gunpoint on three consecutive nights.

Terry, an Alaskan firefighter who slept through the entire gunpoint drama the first night, ultimately figured out that the best way to deal with the soldiers was to feign utter cluelessness. Whereas I spent 15 minutes the first night earnestly trying to explain our largely unexplainable situation with a tourist phrasebook, Terry simplified our dilemma the following two nights by patiently smiling, scratching his head and babbling a steady stream of Grandpa Simpson nonsense to the soldiers. Apparently equating stupidity with harmlessness, the shore patrol left within five minutes — laughing derisively — both times.

Apart from the soldiers and the odd Lao fisherman who showed up at our campsite out of curiosity, we didn’t mix much with the locals during that stretch of river. The lone exception came when we stopped to drop off our garbage and fill up our gas cans at the city of Paksan. There, the proprietors of a riverside tavern (who, incidentally, wasted little time in hurling our carefully accumulated garbage into the river) directed us to the local Buddhist fund-raising carnival.

Unlike, say, a Southern Baptist fund-raising carnival, the Paksan Buddhist fest was a rollicking, drunken affair. Old women aggressively hawked chicken-on-a-stick in the street while old men squatted and sipped rice whiskey in the shadows. Married couples swilled beer at the courtyard tables, while younger couples danced atop a wooden stage to Lao pop tunes (which, after three weeks in the country, still sounded to my ears like an oil drum full of mynah birds being slowly tortured to death, to a synthesized backbeat).

By far the most enthusiastic participants at the festival were the children, who followed us around in packs, shoved candy into their mouths until their chins turned orange and ran screaming from one gaming stand to another. At one booth, a dozen 10-year-olds crowded around a kiddie craps table, placing 100-kip (2-cent) bets onto a grid featuring cartoon fish, crabs and shrimp. When Sarah squatted in their midst and won five consecutive pots by betting on the crab, the children stared at her in amazement.

After we left Paksan, we took the Mik Sip on a spontaneously conceived three-day excursion up the Kading River — a canyon-girded Mekong tributary where the birds roared in their canopy hideouts, the water buffalo fornicated shamelessly on the shore and shafts of sunlight pierced the bottle-green water down to clean sand bottoms.

By the time we had returned to the Mekong, Robert, Sarah and Terry were due elsewhere. The itinerant trio caught a bus back to Vientiane at Kading Village — leaving Chris and me to navigate the remaining stretch to the Cambodian border, Khemmarat rapids and all, by ourselves.

Part V: Rapids, ruins and the end of the river

By the time Chris and I started down the southeast bend of the river above Thakaek, the Mik Sip had traveled more miles down the Mekong than most Lao citizens travel in their lifetimes. As we steered our northern-style fishing vessel into the southern reaches of the river, we may as well have been driving a dogsled into downtown Dallas. Fishermen in small, long-tail powered dugout canoes stared in confusion or bemusement as Chris and I thumped past in a high-gunneled, canary-yellow craft that was twice as long and half as maneuverable as anything else on the river.

Since the logistics of a two-man crew pretty much precluded socializing, Chris and I drove straight through to Thakaek. Piloting in shifts, we stuck close to the tobacco fields of the Lao shoreline as the river gradually widened. By late day, we could no longer make out the fishing boats on the Thai side of the Mekong.

When the sun went down amid an orange halo of burn-off smoke from the Thai fields, we drove the last two hours to Thakaek by moonlight. In the dim neon glow, the shores of the Mekong dissolved into a bluish veil of noises. The rattle of the Mik Sip’s engine reverberated from the Lao bank with a warping echo, sounding like some back-masked message from Babel; dim strains of karaoke drifted across the waters from the Thai shore, as eerie and tuneless as white noise. Whenever Chris shouted to me from the pilot’s seat, it sounded like there were 100 of him in a very large and empty room. Though we certainly weren’t on the river much past 8 p.m., it felt like time had stopped altogether. We pulled into Thakaek as enchanted and spooked as Huck and Jim below the Ohio.

I fell asleep in my hotel room within an hour of arriving, and woke up disoriented at 4:30 in the morning. Hoping to straighten my bearings, I went for a walk through the darkened pre-dawn streets of Thakaek.

If Luang Prabang is a tiny Manhattan, then Thakaek is a Laotian St. Louis — an 1850s-style gateway city, where little girls try on their mother’s lipstick by kerosene lamp light behind the shuttered windows of crumbling mint-green Lao-French homes, and blue banners advertising Pepsodent flutter above dusty piles of red brick in the old colonial town square, and sad chickens screech like broken radios in the moments before sunrise.

As I walked, Nakhon Phanom, Thailand, blazed in electric splendor just across the river — a vision of an alternative future — its riverbanks hemmed with smart concrete walkways, its avenues webbed over with telephone lines, its temples as clean and uniform as McDonald’s franchises.

In a century defined by technological progress and Western standards of living, the Lao shores of the Mekong often feel like a dusty asterisk in the history books. Indeed, some 85 percent of Laotians still survive on a subsistence lifestyle — farming or fishing for food, building their homes from native materials and occasionally bartering for consumer items.

Outside influences look to change all that. Just a few decades after having dropped 2 million tons of bombs on Laos (as part of an ill-defined “secret war” that reduced the peasant culture of Xieng Khouang province to rubble), the United States has already poured $1.5 billion of investment into Laotian modernization and economic-development schemes.

The city of Thakaek, though, symbolizes the potential of a much stronger influence on Lao society: Thailand. In 1996, Bangkok and Vientiane signed a memorandum of understanding to build a bridge connecting Thakakek with Nakhon Phanom. Thus — with the increased flood of Thai commerce bound to arrive on the Lao shore — Thakaek represents how Laos is at a sensitive crossroads: primed for changes that will likely redefine the country in another 20 years.

It has been suggested, of course, that this is a bad thing — that avoiding foreign influences and maintaining the purity of local culture is somehow more ideal. But a close look at Lao culture itself shows how it’s too late to arbitrarily stop time and make judgments of cultural purity. After all, the basic precepts of Lao mythology, philosophy and religion are heavily influenced by the ancient Khmers (who themselves were influenced culturally by India), most Lao pop culture is already Thai-derived and for hundreds of years there was no distinct border between Laos and Vietnam.

All of this in addition to the fact that — even in the charming pre-dawn streets of Thakaek — I never once saw any Lao citizens who could knap flint in the manner of their Stone Age ancestors.

Within two hours of my morning walk, I was back on the river. While I’d been asleep the night before, Chris had invited Liz and Duncan, a good-natured young English couple, to join us for the final stretch.

The four of us made it two days downriver from Thakaek — and not more than an hour past Savannakhet — when I personally drove the Mik Sip over a submerged rock shoal, snapped the propeller off and set us adrift in the swift current.

“Well,” Chris said with a trademark phlegmatic drawl that indicated he was panicking, “if we don’t start paddling right now, we’re gonna lose this boat.”

Thus began our descent of the Khemmarat rapids.

If any English-language travel guidebooks offer the slightest shred of specific advice on navigating difficult sections of the Mekong, I am not aware of their existence.

Going into the Khemmarat rapids, the best description of our watery obstacle came from Marte Bassenne’s 1909 travelogue — which vaguely placed the rapids somewhere between Savannakhet and Pakse, and grimly noted that this stretch of the Mekong River “is like a common grave of unlucky victims, because one seldom finds a corpse.” Francis Garnier, whose expedition team portaged around the rapids in 1866, wrote of Khemmarat: “Nothing can express the horror of this spot, where the yellow waters twist over and through the long narrow pass, breaking against the rock with a fearful noise.”

Chris and I had disregarded the hyperbole of our French predecessors for three reasons. First, we were in the middle of dry season, so the rapids would not be as fierce as Garnier and Bassenne had witnessed. Second, we had purchased a sheaf of detailed topographical maps of the area from the national geographic service in Vientiane. Third, we figured that the ubiquitous Lao fishermen — who had been quite helpful in pantomiming instruction thus far — would warn us if we were about to motor into certain death.

After I broke the propeller on the shoal below Savannakhet, we were able to paddle to a broken concrete pylon away from the current and save the boat. During the French colonial era, that pylon might have warned me off the rocks in the first place. Unfortunately for us, the Savannakhet to Pakse portion of the river isn’t used for long-haul commerce anymore, and the century-old pylons have been worn down to amorphous lumps of cement and cobbles. For our purposes, the pylon did little more than provide me with something to steady the boat on as Chris plunged under the stern to install a new propeller.

Once the Mik Sip was up and running, we headed downstream for what would become 36 continuous hours of melodramatics. Low water had indeed provided us with a weaker current — but it had also split the river into a foaming braid of channels splayed out amid a maze of rocks. When we weren’t churning through the whitewater, it seemed, we were getting stuck on a shoal.

Chris drawled nervously at us the whole time, and continuously improvised methods of staving off disaster. When the channel narrowed to a boil, Chris put Liz in the bow and had her signal upcoming dangers. When waves from the rapids began to wash over the gunwales, he had me squat over the engine with a plastic mat so we wouldn’t stall out in the middle of the whitewater.

Around sundown the first day, we eddied-out near a huge riverside sand dune that made for a perfect campsite. After collecting my share of the night’s firewood, I went down to the water’s edge to watch the first stars come out. Something about the day’s dangers had sharpened my senses; I listened to the languorous murmur of the river with an acute feeling of joy. As I breathed in, I imagined the tiny bits of oxygen attaching to the wet walls of my lungs and sifting off into my bloodstream.

Just after noon the following day, we came upon the most daunting rapid we’d seen yet: a fat tongue of water that spilled out in a fury between two huge black rocks. Intimidated, we stopped for lunch.

Positioning himself high on the bank above the rapid, Chris peeled a hard-boiled egg and stared out at the foaming water with an edgy silence. When he’d finished eating, he came down from his perch. “To hell with it,” he said.

Five minutes later, he took us straight down the middle of the tongue, and that was the end of the Khemmarat rapids.

Years ago, Lao myth tells us, men and gods used to meet. As generally happens in such situations, the humans blew that arrangement by being foolish and arrogant.

When mankind insolently refused to seek a livelihood beyond hunting and fishing, the gods flooded the world. Three chieftains managed to escape the flood by building a floating house. When the waters receded, the gods gave the chieftains a buffalo, so they could plow the earth, plant crops and live in a civilized manner. When the buffalo died, three gourds grew from its nose — and when the chieftains cut open the gourds, humans poured out to populate the world.

Below the rapids of Khemmarat, where the Mekong gradually twists its way down into an isolated, sun-baked canyon, one is tempted to take this myth at face value. The only inhabitants of this limestone gorge — which is fluted with ledges and fringed at the top with virgin forest — were gypsy fishermen, who seem to have secretly dodged the mythic flood and held on to their uncivilized ways. Living directly on the canyon cliffs in thatch huts, and climbing from ledge to ledge on an elaborate system of wooden ladders, the river gypsies looked otherworldly — larger than life — like they were impassively waiting for Jesus to come back and make them fishers of men.

We camped that night on a narrow dune that hadn’t seen footprints in ages. I entertained myself for the good part of an hour just walking the contours of the sand, turning every so often to watch the tiny avalanches set off by my presence. When I awoke in the bow of the Mik Sip the following morning, the sand next to the boat was laced with the tracks of voyeuristic rodents.

South of the canyon, the Mekong swelled to a width of over a mile and doglegged away from Thailand. On this clean blue stretch of river, the waters were once again awash with passenger ferries and huahoua-leim freighters, plying the stretch between Pakse and the Thai border.

By the time we’d arrived in Pakse to order an enormous restaurant dinner and toast our survival, Chris was already overstaying his visa. He departed for Thailand the next day, leaving me the sole owner and most experienced operator of the Mik Sip.

In a way, my Mekong adventure ended with the passage through the rapids and the canyon.

This is not to say that the river becomes any less interesting, beautiful or even challenging below Pakse — it just means that after Pakse I assumed the helm of the Mik Sip, and I wasn’t able to pay attention to much beyond the course of the river and the boat itself.

Like Twain had in his river piloting days, I had lost the river by learning the river: I had traded aesthetics for science. But for me — as for Twain — the challenge of driving the riverboat was reward enough for all the lost splendor.

As we made our way downriver, Liz and Duncan would point out the big white-and-brown birds of prey soaring above, the abandoned fishing villages that sagged like shipwrecks on the sandbars or the finger-sized fish that jumped from the water and skittered along in our wake. We even stopped for several hours at the ruins of Wat Phou — a haunting, half-collapsed sandstone temple where pre-Angkor Khmer statues lie headless, half-buried and stained with Pepsi, and one’s sense of being amid “time-worn dreams of adolescent reverie” (as Garnier put it) is offset by the trash-strewn, weed-tangled feeling of touring a recently abandoned drive-in movie theater.

For the most part, though, I was lost in a curiously satisfying world of pylons, channels and currents — of bilge water and the correct fuel mixture for our 10-horsepower Briggs and Stratton.

Two days below Pakse — 22 days after having first boarded the trusty yellow boat — I drove the Mik Sip into Cambodian waters on the Lepou tributary of the Mekong.

Just above its Laotian terminus, the Mekong enters a new geophysical region — splitting into dozens of channels and thousands of small islands. Appropriately, the Lao name for the area is Siphandone — “4,000 Islands.” Graced with freshwater dolphins, peaceful lagoons and majestic waterfalls (including Khong Phapheng, reputedly the world’s widest waterfall), Siphandone has no rival as a landlocked tropical island paradise.

After our final day on the river, Liz and Duncan threw me a farewell dinner on Khong island, the largest and most accessible of the 4,000 islands. After dinner, we went to the community basketball court, where a raucous pop concert was already under way.

Onstage, a group of teenage girls performed a sequence of bump-and-grind dance moves to the rhythms of the music. Dressed in frumpy orange dresses and wearing socks under their sandals, the girls looked strangely dated, like something I might find in the pages of my mom’s 1961 Westphalia, Kan., high school yearbook.

The Lao pop music itself (which is perhaps still recovering from a short-lived 1976 Communist edict banning rock music, cosmetics and animal sacrifices) was awful beyond metaphors.

The following morning, I rose early to take the pre-dawn ferry to the mainland, where — in deference to my expired visa — I would catch a series of buses to the Thai border. Joining me at the first bus stop was one of the orange-dress dancing girls from the night before. Standing there in her subdued street clothes — sleepy and wistful — she looked like a morning-after Cinderella.

Which is what I felt like, after three weeks of clean sand, campfires and silent sunrises on the shores of the Mekong.

[This essay originally ran as five-part series in Salon, July 6-10, 1999]