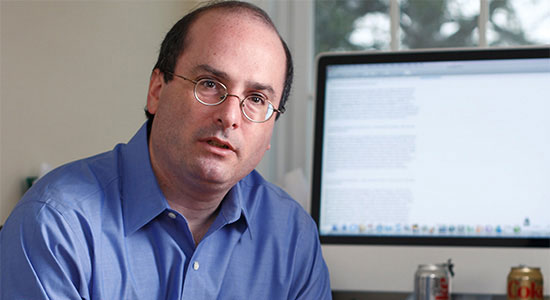

David Grann is a staff writer at The New Yorker. He has written about everything from New York City’s antiquated water tunnels to the hunt for the giant squid to the presidential campaign. The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon, published by Doubleday, is Grann’s first book and is being developed into a movie by Brad Pitt’s Plan B production company and Paramount Pictures. Grann’s stories have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe, and the Wall Street Journal; they have also been anthologized in collections such as The Best American Crime Writing and The Best American Sports Writing. He holds master’s degrees in international relations from the Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy as well as in creative writing from Boston University. After graduating from Connecticut College in 1989, he received a Thomas Watson Fellowship and did research in Mexico, where he began his career in journalism. He currently lives in New York with his wife and two children.

How did you get started traveling?

Ever since I was young, I’ve been drawn to adventure tales, ones that had what Rider Haggard called “the grip.” The first stories I remember being told were about my grandfather Monya. In his seventies at the time, and sick with Parkinson’s disease, he would sit trembling on our porch in Connecticut, looking vacantly toward the horizon. My grandmother, meanwhile, would recount memories of his adventures. She told me that he had been a Russian furrier and a freelance National Geographic photographer, who, in the 1920s, was one of the few western cameramen allowed into various parts of China and Tibet. (Some relatives suspect that he was a spy, though we have never found any evidence to support such a theory.) My grandmother recalled how, not long before their wedding, Monya went to India to purchase some prized furs. Weeks went by without word from him. Finally, a crumpled envelope arrived in the mail. There was nothing inside but a smudged photograph: it showed Monya lying contorted and pale under a mosquito net, wracked with malaria. He eventually returned, but because he was still convalescing the wedding took place at a hospital. “I knew then I was in for it,” my grandmother said. She told me that Monya became a professional motorcycle racer and when I gave her a skeptical look, she unwrapped a handkerchief, revealing one of his gold medals. These stories, along with photographs of his journeys, always filled my imagination, and gave me some sense that there was some other place to go. After college, I spent a year on a research fellowship in Mexico and have been traveling ever since.

How did you get started writing?

My interest in traveling and writing were always of a piece. Just as I loved to hear stories that put you in “the grip,” I wanted to tell them. When I lived in Mexico, I began writing freelance travel articles for a local magazine, even though it paid only a few pesos.

What do you consider your first “break” as a writer?

When I got my first full-time job in journalism at The Hill newspaper in 1994. I still didn’t have much journalism experience and was hired as a copy editor. The paper had all the wonderful energy and chaos of a start-up enterprise, and before long I was executive editor. After that I went to The New Republic. I was supposed to be covering Congress, but I kept wandering off my beat to investigate stories about con men, mobsters, and spies.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

When I’m researching a story like The Lost City of Z, safety and logistics are inevitably an enormous challenge. How will I trek through the jungle? How will I make contact with Amazonian tribes? Yet ultimately the greatest challenge in every story — whether I’m searching for a lost city or chasing the giant squid — is to uncover some deeper truth about the subject.

What is your biggest challenge in the research and writing process?

For me finding the right story idea is often the hardest part. If I can find a subject that is compelling enough — indeed, that consumes me with obsession—then it’s a lot easier to overcome all the other obstacles, from coping with logistical nightmares to persuading people to talk.

Have you ever done other work to make ends meet?

Early on, when I wasn’t sure how to be a professional writer, I did lots of other things. I tried teaching junior high school and applied for various research fellowships. But ever since I got my first full-time job at The Hill, I’ve been pretty lucky to make a living doing what I love, if sometimes with a little help from my wife.

What authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

When I first read Gay Talese and Joan Didion, I realized the possibilities of narrative nonfiction. Their journalism is grounded in facts but is about more than simply recording them; at its best, their work rises to literature.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into literary journalism or travel writing?

Well, in this current economic climate it’s all a bit daunting, as fewer places have the resources to fund travel and long-term reporting. But I still believe — perhaps naively — that there will always be a place for that kind of work. And indeed as less people do it I think there will be a greater hunger for it.

What is the biggest reward of life as an itinerant writer?

I’ve had the opportunity to chase giant squid in the middle of a squall off the coast of New Zealand, sit across from members of the Aryan Brotherhood in maximum security prisons, journey nearly a thousand feet beneath the streets of Manhattan with tunnel diggers (“sandhogs”), and trek through the Amazon looking for a lost city. Otherwise, I would have led an awfully boring life.