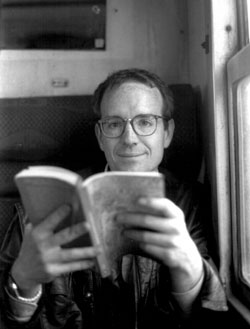

Rory MacLean was born and educated in Canada. His five books, including best-sellers Stalin’s Nose and Under the Dragon, have (according to the Financial Times) challenged and invigorated travel writing, and are (according to John Fowles) among works that “marvellously explain why literature still lives”. He has won the Yorkshire Post Best First Work prize and an Arts Council Writers’ Award, was twice short-listed for the Thomas Cook Travel Book prize and was nominated for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary award. He lives with his wife and two-year-old son in a rural Dorset village in England.

How did you get started traveling?

My earliest memory is of cobbling together a cardboard world atlas, with crayons and sticky tape, and inventing the roads which lay between the few countries I knew. So the road has always been a place I call my own.

How did you get started writing?

I don’t remember a time when I didn’t write: short stories, school plays, student newspapers, home movies. For years I dreamed of being a film director. To that end I wrote dozens of scripts, following every trend, choosing ‘saleable’ subjects rather than stories that moved me. The result was a series of flops, tame thrillers and busted blockbusters. But after each movie, to regain my sense of self, I took off traveling. And soon I realized that more than anything else I loved journeying into territory unknown (to me) and writing about the people and places met along the way.

What do you consider your first “break” as a writer?

In 1989 I submitted a story on Prague to the first Independent newspaper travel writing competition, and won. That led to a commission to write a book on eastern Europe. Then Gorbachev was kind enough to knock down the Berlin Wall, making my subject highly topical. The resulting book, Stalin’s Nose, made the UK top ten.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

I’m not a great linguist so I carry a reliable phrasebook – in memory of a young English friend who asked to be taught a Greek expression for great pleasure. At the disco that evening she cried out, ‘I’m so happy I’m going to come.’ Which caused considerable consternation on the dance floor.

What is your biggest challenge in the research and writing process?

As a travel writer I considered myself to be less a geographer of place, more a geographer of the human heart. Individuals move me more than mountains or national histories. In my writing I concentrate on the remarkable stories of ordinary men and women who have been separated by borders, fear, even time and death. In retelling their stories I try to empathize with their lives, society and time.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint?

Making ends meet. Even though I’ve had two UK best sellers and my books have been translated into five languages, my retirement pension is looking fatally under-funded. But if you’re serious about writing then you just have to take the risk.

Have you ever done other work to make ends meet?

I once sold encyclopedias. Tried to sell encyclopedias. For a week.

What authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

A Time of Gifts, Patrick Leigh Fermor’s fluent, exotic account of his youthful journey from London to Constantinople, published more than 40 years after the event. It is a book that makes everything seem possible. And Raymond Carver’s short stories — honest, direct, lean and adverb-free, each creation a triumph of minimalism which conjures extraordinary hope from the minutiae of ordinary lives. No word spare. Nothing wasted. Remarkable and poetic inventions. Plus of course Mary Poppins, for its healthy disregard for authority, especially bankers, its promotion of women’s rights and its emphasis on the role of fantasy.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

Write. Write. Write. Then write some more. And if you feel you’ve had enough, it’d probably be a better idea to do something sensible like becoming a dentist or raising rabbits.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

The opportunity to try to understand other peoples, societies and histories. Then to communicate that passion with others. And through that process to start to know ourselves better.