Dustin Grinnell is an American travel writer, essayist, and fiction writer who lives in Boston. He is the author of Lost & Found: Reflections on Travel, Career, Love, and Family (Peter Lang), a finalist in the 2024 Next Generation Indie Book Awards. His travel writing has been featured in many publications, including Salon, The Expeditioner, Perceptive Travel, Intrepid Times, Narratively, Lost Magazine, The Good Men Project, Living Now Magazine, TravelMag, Wanderlust: A Travel Journal, Wayfarer Magazine, Outside Magazine, and the travel sections of The Boston Globe, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and The Washington Post. His travel writing has earned him two Solas Awards for Best Travel Writing and an honorable mention in the North American Travel Journalists Association Travel Media Awards. He’s also the author of several books of fiction, including most recently The Healing Book (Finishing Line Press) and The Empathy Academy (Atmosphere Press). His podcast, Curiously, offers thought-provoking discussions that aim to expand your perspective and satisfy your curiosity about the world.

How did you get started traveling?

I grew up in northern New Hampshire in the White Mountains. I was always outside in the backyard or woods, exploring. I spent much of my childhood skiing and hiking the White Mountains. I even kept a checklist of all the 4,000-footers, and got well over halfway through the list by adolescence. As a kid, I was an avid reader, especially of adventure stories; I remember loving Gary Paulsen’s The Hatchet, about a thirteen-year-old boy who survives alone in the Canadian wilderness after a plane crash, using only his resourcefulness and a hatchet.

Every summer, my dad took my brother and me to Martha’s Vineyard, where we’d leave behind the car, bring only our bikes, and camp—a tradition that led me to appreciate self-sufficient travel. In college, studying abroad in New Zealand was a transformative experience, solidifying my love for travel and adventure. In my twenties and thirties, that passion led me to explore 20+ countries, chasing experiences like running the Paris Marathon, surfing in Costa Rica, and trekking through China’s Tiger Leaping Gorge.

I realize that travel feels ingrained in me—perhaps because, after my parents divorced, they both moved around a lot. My father, a builder, would build a new house, we’d live in it for a few years, and then he’d start over, repeating the cycle. That experience taught me that home could be something transient, always shifting. At the same time, I’ve wondered if this early instability made me crave a sense of stability, steering me toward jobs with more security than the unpredictable life of a travel writer. It’s a complex tension I’m still trying to untangle.

How did you get started writing?

I didn’t grow up wanting to be a writer. My passion was science, and I devoured nonfiction books on topics that fascinated me, from cosmology to evolution. In high school, I won the Brown University Book Award, which recognized excellence in written and verbal communication—a message that I might have a talent for writing. I foolishly brushed off that realization and instead pursued neuroscience and pre-med in college. I decided to go to graduate school to study it further.

A few months into my PhD program, I realized that what I enjoyed most wasn’t doing the science—it was thinking and writing about it. So, I approached the research affairs office and asked if I could write science articles, and the editor graciously took me under her wing. When I left grad school with a master’s in physiology, I took on writing jobs with science or research organizations while exploring creative writing on the side. I initially gravitated toward science fiction, crafting stories in the spirit of my literary hero, Michael Crichton.

The spark for my first travel piece came during a travel writing class at Boston University taught by David Able—a journalist, travel writer and documentary filmmaker—who asked us to write about a personal travel experience. I decided to write about hiking Mountain Kilimanjaro. The piece explored trusting my intuition during a questionable situation with a local guide. To my surprise, it was published in The Philadelphia Inquirer. That experience opened my eyes to travel sections as a promising market for new writers. From then on, I wrote travel pieces about my adventures and pitched them to newspapers and magazines, gradually building my portfolio.

What do you consider your first “break” as a writer?

My first break came with a piece for The Boston Globe about learning to ride a motorcycle to Walden Pond. It was then that I began considering travel writing more seriously. I decided to pursue my proposal independently and travel to China to study Traditional Chinese Medicine, and use that experience as the foundation for a broader, year-long journey. At 33, I left Corporate America to take a year off for what I saw as a modern-day walkabout, inspired by the Australian tradition of seeking spiritual growth in the wilderness.

My journey began with a three-week backpacking trip through China, followed by six weeks of writing and preparations at my father’s home in New Hampshire, and then a 4,300-mile motorcycle ride to Southern California. This trip was romantic, even quixotic, but I had been craving a departure from routine. In American life, we lack formal initiations into adulthood. My trip became a self-imposed rite of passage, exploring who I was and what I wanted. When I got to California, I created a video of my travels and submitted it to Outside Magazine’s travel section. It felt like a breakthrough moment for me when they decided to publish it in their adventure travel section. The journey wasn’t without hardship, however. Stress, financial instability, and isolation tested me, forcing me to confront vulnerabilities. It was a humbling experience, revealing the limits of my overconfidence. Failure became a teacher, showing me that growth often emerges from setbacks.

As a traveler and fact/story gatherer, what is your biggest challenge on the road?

Finding the story can be a challenge. Often, I don’t discover it until long after the trip—like when I visited Switzerland last year and, on a whim, decided to search for an old friend’s cabin in Lauterbrunnen. This approach to writing means I’ve always had to take a leap of faith: financing my own travels to find the stories, then coming home to write them. Only afterward would I begin searching for a publisher. For example, it took eight months and many rejections after my trip to Switzerland before Wayfarer Magazine finally offered to publish the story. This approach—writing “on spec,” or without a guaranteed publication—isn’t for everyone. But if you want to do it, you just have to take the plunge.

What is your biggest challenge in the research and writing process?

I’ve never had trouble getting words down on paper. When I decide to write, I dive in—jotting insights, organizing ideas, and developing the story. The biggest challenge, however, is often the details. What was the exact date of that trip? What route did I take? Which towns did I visit, where did I eat, who did I meet and what did they say? Over time, I realized I had to capture these details during my travels, or they’d be lost forever. Now, whenever I travel, I’m a meticulous notetaker. That said, I have a rare condition called aphantasia that complicates reflecting on and writing about my travels. I don’t have a “mind’s eye,” so I can’t picture images in my mind or vividly recall sensory details like smells or sounds. So, I’ve seen the sunrise from the summit of Kilimanjaro, skied the Remarkables in New Zealand, and partied until dawn at the Las Fallas festival in Spain, but I can’t summon those memories visually in my mind. Instead, I rely on my notes and a conceptual understanding of the experiences. In some ways, I wonder if this limitation is what drew me to write about my travels in the first place. Without a mind’s eye to revisit my adventures, writing allows me to preserve them in a way I can’t otherwise.

What is your biggest challenge from a business standpoint?

The biggest challenge has been coming to terms with the reality that making a career out of travel writing, especially travel literature, feels nearly impossible in this age. I always imagined my ideal job would involve working for a magazine with an editor who’d send me anywhere and tell me to bring back a story. I’d do it happily and professionally. But increasingly, with the rise of the internet and social media, alongside the closures and layoffs of magazines and newspapers, travel writing feels more like a hobby you pursue while holding down a full-time job that actually pays. That’s been my reality over the past decade, balancing marketing writing jobs while pitching stories as a freelancer. I will say that it seems possible to make a full-time living producing travel content on social media, but being an influencer just doesn’t appeal to me.

Have you ever done other work to make ends meet?

I’ve always had a full-time job writing content for organizations, while writing and pitching my creative nonfiction and fiction on the side. I’ve developed something of a routine of working a corporate job for a few years, building up my bank account, and then cashing out to fund the next adventure. As I mentioned, I’m not sure how to support myself solely through travel writing, as so many markets have dried up and many opportunities have been demonetized. Lately, I’ve grown weary of being a hired gun for organizations—promoting, spinning, and selling. I long to do something unbiased and more meaningful. Yet, the stability provided by corporate work allows me to pursue creative, speculative projects that often don’t pay or takes years to materialize.

What travel authors or books might you recommend and/or have influenced you?

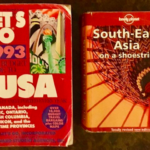

First off, I have to give a shout-out to Lonely Planet! I always buy a Lonely Planet guidebook before I leave home. In terms of travel books, I’ve enjoyed travel memoirs like Eat, Pray, Love and A Walk in the Woods, but I’m especially drawn to journalistic accounts of travelers, like Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air. His book Into the Wild left a lasting impression on me in my twenties, inspiring me to drive across the United States one summer while I was in college. In my thirties, I felt that same urge to travel cross-country again, this time by motorcycle, after reading Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. I also like books that involve adventure travel but center on a big idea, like Lawrence Gonzalez’s Deep Survival. The book I keep returning to, though, is Michael Crichton’s Travels. It’s not a traditional travel book—it’s a memoir of his early years in medical school, his decision to become a writer, and his adventures around the world. Crichton blends personal reflections with insights into science, philosophy, and spirituality, offering a fascinating look at both the outer world and his inner self. Additionally, I’ve been meaning to read the 2024 collection of Anthony Bourdain’s travel writing—his documentary sort of changed my life. If you’re interested in books on the craft of travel writing, Lonely Planet’s Guide to Travel Writing is excellent. I’m also a fan of A Field Guide for Immersion Writing, which includes a section on travel writing but focuses on creative nonfiction. The best way to learn, though, is to read great travel writing and take it apart to see how it works.

What advice and/or warnings would you give to someone who is considering going into travel writing?

Discover what kind of travel writer you are. Generally speaking, I think there are three types of travel writing: service writing, like “Five Things to Do in Rome for History Buffs”; guidebook writing, like Lonely Planet; and travel literature, like Paul Theroux’s books. I’ve always been drawn to travel literature—long-form, personal narratives that transport us to new places and tell a story, often of transformation, while using techniques like plot, character, and dialogue to immerse and entertain. I think people should write what compels them, but I’m concerned about the future of service pieces and guidebook writing in the age of artificial intelligence. While human writers will always be necessary for on-the-ground reporting, AI can produce many types of travel writing quickly, efficiently, and cheaply, potentially reducing job opportunities in these areas. As for building a successful freelance writing career, when I went freelance for a year, I began reflecting on my experiences and published an article for Writer’s Digest about the lessons I learned through the lens of my father’s approach to self-employment as a builder.

What is the biggest reward of life as a travel writer?

It’s always nice to see your name in print, to open a magazine or pull up a webpage and see the piece of writing your labored over right there in your hands—in other people’s hands! If you’re born with an above average amount of curiosity, there’s no better way to fuel it than travel. For me, there’s nothing quite as exciting as setting off for a new place. In On the Move: A Life, Oliver Sacks celebrates his love for movement—through motorcycling, swimming, and weightlifting—as a profound source of freedom, focus, and self-discovery that mirrored his intellectual and emotional journeys. I couldn’t agree more. I think traveling helps you figure out who you are, or at least reminds you of who you are. There’s something about leaving behind your routines and rhythms that puts you in direct contact with the world and makes you realize who’s having the experience.